Principal Keith France visits a classroom during the first day of school at Elizondo Elementary School in North Las Vegas Monday, August 29, 2011.

Thursday, Sept. 1, 2011 | 3:46 p.m.

The Turnaround: Elizondo Elementary School

KSNV reports on efforts to turn around struggling Elizondo Elementary School, Sept. 1, 2011.

Related stories

- Western High School’s goals include more parent involvement, higher expectations (8-31-2011)

- Mojave High School’s turnaround starts with pride (8-30-2011)

- Principal Antonio Rael: To succeed, help from community a must (8-30-2011)

- At Chaparral, clean house, new faces, fresh start (8-29-2011)

- Principal David Wilson: Laying down the law to change the culture (8-29-2011)

- Five struggling schools embark on a journey to improve education (8-28-2011)

- Sun to track progress of 5 struggling schools (8-28-2011)

- Discussion: School District’s top officials sit down with the Sun (8-28-2011)

- Shifting demographics demand greater urgency in improving schools (8-28-2011)

- How community views education must change if schools are to be fixed (8-28-2011)

Map of Raul Elizondo

Keith France raises his hand in a peace sign high above the crowd like a conductor about to lead an orchestra through a Mozart symphony.

The cacophony from nervous kindergartners and camera-carrying parents subsides. All is quiet on the asphalt blacktop baking in the blistering August sun.

It’s the first day of school and the tall, goateed principal is welcoming his youngest students to Elizondo Elementary School. Months of preparation — hiring staff, cleaning the campus and setting up curricula — have brought France to this day.

Now begins the hard work to turn around this struggling North Las Vegas elementary school, near the industrial outskirts of town.

Elizondo, a 13-year-old school named after a fallen North Las Vegas police officer, is one of five “turnaround” schools ranked among the bottom 5 percent of schools in the Clark County School District.

Less than half of the students at Elizondo are proficient in math and reading. Only 17 fifth-graders — 18 percent — passed the writing portion of the Criterion Referenced Test last year. Elizondo has failed to meet federal standards under No Child Left Behind for the past six years.

France was shocked by the students’ poor performance. “The kids here weren’t getting what they were supposed to,” he said, his voice rising. “Something’s wrong here.”

•••

The School District chose Elizondo to be among the five schools to benefit from a federal grant program to improve troubled schools. Although the district received $8.7 million from the School Improvement Grant, it was to help only four schools. Elizondo was left in the lurch.

No matter. District officials were adamant about fixing Elizondo. The School District footed $150,000 — less than half of what Hancock Elementary received from the grant — to implement the turnaround at Elizondo.

As with most turnaround schools, the principal was replaced, and staff had to reapply for their positions. No more than half of them could be rehired. Teachers were given $1,750 signing bonuses — an incentive to work at a challenged school.

France, a former principal at Lincoln Elementary, replaced 26 of 40 teachers and most of the support staff. He wanted more than teachers: Strong leaders who could collaborate and innovate new ideas to improve education.

“I’m very optimistic because the staff is so strong and so ready,” he said, calling them his “dream team.” “They really have that desire to move these kids up.”

•••

Connecting with students and parents at a school with a high transiency rate and a high Hispanic population will be difficult, but France is determined. Only a half-dozen parents showed up for the two meet-the-new-principal events this year, although hundreds of parents and students showed up for an open house last week.

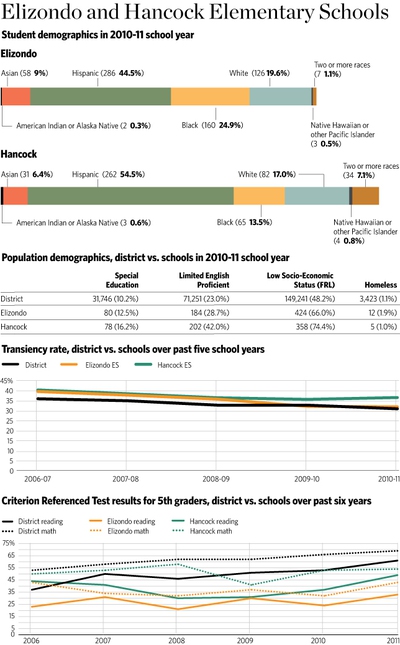

The former music teacher — who always has jazz, rock and classical music playing in his office — has been learning Spanish. It’s hard, but he wants to be in tune with his school’s Hispanic population, about 45 percent. Translators will be at every school meeting and in the main office. Previously, no one answering phones spoke Spanish, France said.

“The Hispanic community had a hard time in the past because they didn’t get translators,” he said. “They basically had to figure out what (teachers and principals) were saying. It was very uncomfortable for (parents), and I will not let that happen this year.”

Many students come and go as their family life and financial situations change, France said. “The transiency rate is so bad here that just as you start to build trust with parents and students, they’re gone — replaced by new people who don’t trust the school.”

France knows all about the transient life, having grown up with it. When his father fell ill, he lost his trucking job and then the family home. France lived with his grandmother in a trailer, bouncing from school to school like a pinball. His family’s struggle with poverty drove him to go to college, France said.

“When I talk to parents and students, I know where they’re coming from,” he said. “When I hear stories about having to choose between new school clothes and putting food on the table, believe me, I understand that. I’ve been there. I know what that’s like.”

Over the years, some Elizondo students have acted out frustrations stemming from their economic differences and struggles, vandalizing the restrooms and bullying other students, he said.

France is implementing a uniform policy this year, something he picked up during his travels abroad to South America. Lunch breaks will be staggered, and students let out of school at different locations around campus by grade level. France hopes these measures will curb bullying.

Elizondo isn’t just a turnaround school. This year, it became one of seven Clark County schools managed by EdisonLearning Inc., a controversial New York-based for-profit education company that has had mixed success. The district forks over all of a school’s per-pupil funding to Edison, which implements its curriculum, adopts a longer school day and conducts frequent student assessments at select district schools. Edison, which will use district teachers, also provides professional development for them: training, feedback and daily opportunities for collaboration.

Elizondo will still abide by the district’s academic standards and policies, but the arrangement with Edison gives France more autonomy in trying to turn around the school.

•••

Back on the blacktop, a sweaty, but jovial France finishes leading the Pledge of Allegiance and ushers the kindergartners into school. Tears are shed, hugs are given and one small boy is dragged away from his parents, bawling.

The day is all about new beginnings, not only for students but also for France. “This turnaround is like opening a brand-new school, and I’ve never opened a school before,” he said, smiling.

It’s been a long summer. France has been working nonstop — weekdays and weekends — forgoing overtime pay. He seems stressed about the “new” school, losing sleep over new teachers, new students, a new year. The school even has a new logo — a fierce-looking bulldog that represents the bold changes happening at Elizondo.

There’s a lot expected from France and his “dream team”: Academic gains of 15 percent, an increase in parental participation and a successful implementation of a new curriculum. He’s got to make it happen, France said.

“What’s the purpose of a dream team?” he asks rhetorically. “It’s to beat everyone else and be high scoring. That’s what I expect.”

With a new principal and a new mascot, Elizondo Elementary School, located in industrial outskirts of North Las Vegas, hopes to successfully turn the school’s level of achievement around. The school is under pressure to improve test scores, and with only 19 of last year’s 110 fifth-graders passing the writing test, it has some of the district’s lowest scores.

More than 65 percent of Elizondo students are classified as having low socio-economic status. With a high transiency rate and a large Hispanic population, the school is focused on working with students to overcome their familial and financial changes.

This year, more than half the teachers have been replaced and student achievement is on the top of the list. Principal Keith France has extended the school day by 70 minutes. Students must now wear uniforms, lunch breaks are staggered and students are let out of school at different locations around campus by grade level to curb bullying.

Although Elizondo offers an unique full-day kindergarten program that benefits many low-income families, the program has caused class sizes to swell above the state average of 30 students per kindergarten class.

Elizondo differs from other Clark County schools not only because it’s a turnaround school, but because it’s also managed by EdisonLearning Inc., a controversial New York-based for-profit education company that has had mixed success. The school still must abide by district academic standards and policies.

- Year built:

- 1998

- Mascot:

- Bulldogs

- Principal (Year Hired):

- Keith France (2011)

- School motto:

- “Learners today, leaders tomorrow”

- Enrollment:

- Approximately 654

- School Report Card:

- 2010-2011

Compiled by Aida Ahmed

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy