Wednesday, Aug. 31, 2011 | 2 a.m.

Related column

The Turnaround: Western High School

KSNV reports on Western High School and the challenges it faces in turning around student achievement, Aug. 31, 2011.

Related stories

- Mojave High School’s turnaround starts with pride (8-30-2011)

- Principal Antonio Rael: To succeed, help from community a must (8-30-2011)

- At Chaparral, clean house, new faces, fresh start (8-29-2011)

- Principal David Wilson: Laying down the law to change the culture (8-29-2011)

- Five struggling schools embark on a journey to improve education (8-28-2011)

- Sun to track progress of 5 struggling schools (8-28-2011)

- Discussion: School District’s top officials sit down with the Sun (8-28-2011)

- Shifting demographics demand greater urgency in improving schools (8-28-2011)

- How community views education must change if schools are to be fixed (8-28-2011)

Principal Neddy Alvarez made her way through the thick crowd of students and parents gathered in the quad, all curious to see what changes are being implemented at Western High School. The start of school was approaching, and Alvarez was hosting an open house to unveil the “new Western” to hundreds of freshmen and their families visiting the high school for the first time.

Any trepidation on their part is justified: Western’s students have been performing so abysmally that the school has been targeted as one of five turnaround schools in the Clark County School District. The incoming freshmen will be among the beneficiaries if Alvarez is able to make a difference.

On a blistering August morning, smoke billowed from a nearby barbecue grill. Teachers and coaches chatted up clubs and activities to any listening ear. A student dance group swayed to Spanish music underneath a new shade structure in the quad.

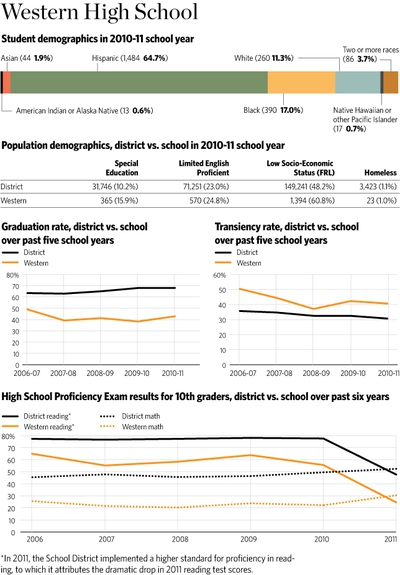

The crowd that gathered was mostly Hispanic, reflective of the school’s working-class neighborhood near U.S. 95 and Decatur Boulevard.

Alvarez smiled and recalled her youth. As a native Las Vegan, Alvarez is a proud product of the School District, having graduated from Chaparral High in 1981.

Things were different then. Alvarez was among the few Hispanics in the formerly mostly white district, the daughter of Cuban refugees who took a chance on Las Vegas to build their American dream.

“The reason my parents came to the states is to be free, and so that I could get a good education,” Alvarez said. “My dad always used to say, ‘The one thing no one can ever take away from you is your education.’ ”

•••

Although Alvarez was a “have-not mixed in with all the haves” at Chaparral, she said she was held to the same academic standards as her more affluent peers. It didn’t matter if she was a Hispanic whose parents didn’t speak English. Her parents and teachers pushed her to graduate from high school and get her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from UNLV.

“I had the same expectations for success as the white kids sitting next to me,” Alvarez said. “That’s what we’re trying to do at Western. We want kids here to believe they can do anything in this world.”

Like Chaparral, Western was once a high-performing high school whose alumni went on to prominent colleges and lofty professions.

When suburban high schools such as Green Valley, Silverado and Centennial opened, they pulled white families — students and teachers — away from Western. Student demographics dramatically changed as historically disadvantaged poor and minority families moved in.

As the years went by, Western became the worst-performing school in the Clark County School District, with the highest dropout rate and the lowest graduation rate among the district’s 49 high schools.

Only 43 percent of students in Western’s Class of 2010 received diplomas, according to School District figures. It’s likely even fewer students graduated because the district’s graduation rate is considered by outside groups such as Education Week to be inflated by as much as 15 percentage points.

Test scores aren’t any better.

Only a quarter of 10th-graders last year were proficient in reading and less than a third passed the math section of the High School Proficiency Exam. Of all the high schools in the district, only Mojave’s test scores were lower than Western’s last year.

Western’s reputation is further spoiled by its rough history.

A nearby shooting last year kept Western on lockdown for hours. Fights are common; 73 students were suspended last year. Students casually talk about gangs — violent ones, ethnic “Cholos” and “party gangs” whose main goal is to get high.

Still, Alvarez counts herself lucky to be the principal of the poor, urban 2,245-student school.

“This is our box of chocolates,” she said. “We’re going to do everything we can to get information to our parents and help their children succeed.”

•••

Western High was selected by the state to receive $2.5 million in federal stimulus money over three years.

As a requirement to receive the School Improvement Grant, the School District had to implement a “turnaround” at troubled schools. That meant principals on the job for more than three years were transferred to other campuses, and all the staff had to reapply for their positions. No more than half could be rehired.

Alvarez became Western’s principal in 2008, and because math scores and graduation rates have been inching up during her tenure, the School District kept her at the helm.

Although it was “sad and tough” to fire half of her staff, Alvarez said she is determined more than ever to transform Western.

“I always have to look at this as my job to do what’s best for the kids,” she said. “I had to make sure everyone on this boat had the same philosophy. If you’re not OK with change, the turnaround won’t work.”

Alvarez is adamant that high expectations will lead to higher academic achievement, no matter the student’s background.

About 65 percent of Western’s students are Hispanic, and nearly a quarter are classified as English language learners. Although educating kids from this neighborhood is difficult, it’s far from impossible, she said.

“Just because you’re at-risk doesn’t mean you’re not capable,” she said. “I’m a bilingual Hispanic person, and I think I turned out pretty well. It’s because I had people who believed in me.”

Hispanic students, just like their peers, need someone to believe in their academic potential, Alvarez said. Too often, society writes off Hispanic kids.

“Kids need to know it’s a mind-set that they don’t think they’re capable,” she said. “It’s about changing that mind-set because people only meet the expectation that’s put out there for them.”

It doesn’t help that society perceives minority parents as not caring about their children’s education, Alvarez said.

Many Hispanic parents do care, but might feel too handicapped by their language barrier to take a role. Schools need to make it easier for parents to become involved in their kid’s education, beyond translating documents and meetings into Spanish, Alvarez said.

Last year, Western opened a family engagement center on the third floor of its main building. A grant from the United Way of Southern Nevada helped furnish the room with computers, furniture and resource books. Its purpose: to help Spanish-speaking parents learn English, computer skills and how to navigate the school system.

“My job is to make parents feel welcomed to come to school,” she said. “Sometimes they’re scared of coming to school, but they care just as much as anyone else about their children’s education.”

•••

Despite the beads of sweat on his forehead, Tommy Anderson refused to shed his crisp black suit and red tie at the open house as parents and students peppered him with questions about Western’s new science, technology, engineering and math academy, a component of the school’s coursework.

Anderson, 41, is the new head of the health occupations program at the academy, which offers students the opportunity to become a certified nurse’s assistant by the time they graduate. It’s a rare opportunity for students at any school, let alone one like Western.

Anderson would know. The 20-year registered nurse grew up in a single-parent household in an inner-city neighborhood of Columbia, S.C. Drugs and gangs, fights and vandalism — all the same issues students at Western deal with — were all around him, he said.

“These kids are stereotyped and labeled, which prevents professionals and teachers from connecting with them,” Anderson said. “It’s not right. They shouldn’t be ruled out of life because they’re from the inner city.”

Anderson credits his pastor, teachers and mother — a nursing assistant — for keeping him on the straight and narrow. After graduating from high school, Anderson enlisted in the military and served as a medic in Iraq during the Gulf War.

Two months ago, Anderson retired from Nellis Air Force Base and turned down several lucrative job offers from hospitals to teach nursing at Western. Job experience qualified him for the position, but he is on an accelerated track to receive his teaching certificate.

It was a calling, he said, to help recruit more minority males into nursing. It makes sense in a city with great demand for quality health care.

Western’s new science academy will offer more than just nursing, however. This year, freshmen can take classes in biomedicine, broadcast journalism and computer science. Some students may even receive college credits for College of Southern Nevada through a dual-credit, college readiness program.

Western’s turnaround is about exposing students to careers and options they might not have even thought about pursuing. These classes are practical and may entice students to stay in school. That’s especially important at Western, which has 41 percent transiency and truancy rates.

Opportunity is everything, and that’s what Anderson wants for his son, Kris, a 14-year-old Western freshman. Although Kris was zoned for Centennial, Anderson applied for a zone variance for him to become a Western Warrior.

Although Centennial posts better test scores, it doesn’t have a nursing program, Anderson said, smiling.

•••

Western is the oldest of the five turnaround schools but doesn’t look its 51 years. The School District has added buildings and renovated Western’s older facilities a half-dozen times over the past decade.

After the annual summer cleaning, the linoleum floors are squeaky clean, the white hallway walls repainted and the maroon “Western Warriors” facade retouched. By December, Western will open a new library, engineering wing and broadcast journalism studio, using leftover funds from the 1998 construction bond issue.

Alvarez hopes the new curriculum and facilities will lure back some of the 760 students zoned for Western who are enrolled at magnet schools and career and technical academies.

Matthew Michaelson, a new math teacher at Western, said he was surprised by how clean and bright his classroom looked. It’s much nicer than his old digs at Palo Verde, he said.

This year, Alvarez reorganized the school to keep each grade together on different floors. The separation builds class unity, but also curbs bullying of younger students, she said. The school day was extended an additional period, and time between classes was shaved by a minute to prevent idling students.

A new shade structure in the quad was erected this summer to entice students to eat lunch outside and reduce crowding — and altercations — in the cafeteria.

Alvarez subscribes to the “broken window theory,” where a single act of vandalism begets more vandalism. As soon as a Western restroom is hit by graffiti, it’s closed until it’s cleaned, she said.

Teachers received training on how to build rapport with students by greeting them at the door, shaking hands and establishing eye contact. Some time this year, Alvarez hopes to post teacher portraits above classroom doors so students can become better acquainted with staff.

“I truly believe that’s how to turn a school around; it’s all about relationships,” Alvarez said. “But we need to look at a child as a child. If you identify them as something else, that can create problems.”

•••

Western’s open house was drawing to a close. Campus tours ended, the food was gone. Fresh, eager faces — new teachers, new students and parents new to Western heard about the big changes on tap this year. Some were excited about the possibility of a turnaround. Others displayed reserved optimism.

Some, such as Western senior Samantha Lauer, 17, and her mother, Christine, were sad to see some good teachers reassigned to other schools. They said Western will never be what it was without some of their favorite teachers.

Others, such as Lanisha Walker, 14, and her father, Leonard, were excited about the new science and health academy, but were unsure about the bevy of other changes.

“It sounds good, but I’d like to see how it works,” Leonard said. “Ideas are great, but it’s how you implement them. I’m hoping it’ll change Western.”

Alvarez made one last go-round at the open house before retreating into the cool comfort of the main office. Adorning a wall is a painted sign: “Honor the Past, Challenge the Future.”

It’s a credo Alvarez hopes to live by this year. There’s a palpable energy in her voice, a clear sense of urgency.

“It’s a social injustice if things don’t get turned around,” she said. “We can’t afford to lose any kids anymore.

“If I fail, it’s not failing me, but them,” she said, pointing outside to her students. “I don’t want to fail them.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy