David Wilson, center, principal of Chaparral High School, eats lunch with students sophomores Alba Martinez, left, and Julian Sanchez in the cafeteria on Thursday, August 18, 2011.

Monday, Aug. 29, 2011 | 2 a.m.

The Turnaround: Chaparral High School

KSNV examines the Clark County School District's turnaround efforts at Chaparral High School.

Related stories

- Five struggling schools embark on a journey to improve education

- Sun to track progress of 5 struggling schools

- Discussion: School District’s top officials sit down with the Sun

- Shifting demographics demand greater urgency in improving schools

- How community views education must change if schools are to be fixed

Map of Chaparral

David Wilson moved among the 24 Chaparral High School students like an old-style preacher beckoning skeptical congregants to rise to their feet to speak. “What do you want from me? What can I do for you?” he said on that recent morning. “You’re my boss. I work for you. I don’t work for anyone else.”

It’s doubtful the students had ever heard such words uttered by a school principal. But Wilson, who arrived at Chaparral five months earlier, was launching his campaign to get the struggling school back on track. And he wanted to make it clear from the get-go: Students are his first priority.

The school was once one of the valley’s best, but it has fallen on hard times.

Wilson inherited a campus where classroom carpets and tiles were blackened with decades of filth. Window panes had been etched by what appeared to have been knives and car keys. The football field was pitted with divots that could injure players and members of the marching band. Air ducts in the gymnasium were covered with grime.

Just three toilets for boys and three for girls were working on a campus of 2,250 students. In an apparent sign of rage toward Clark County School District’s decision to replace Chaparral support staff, human feces were left on restroom floors, and toilets were filled with fetid green water.

Wilson was especially livid about the restroom situation. Students had begged him to make clean restrooms his first priority. The very tone of their plea was sad for a district that 13 years ago saw voters approve a 10-year capital improvement plan.

Wilson took photos of what he found and showed them to Superintendent Dwight Jones. The new principal was adamant. “This is a bunch of bullshit. This is not going to fly,” Wilson said. “My kids are not going to live and learn in a facility like this.”

Jones was stunned. “How could we ever expect kids to actually say that going to school matters and the adults in this building care about me when we see this filth and squalor?” he said. He ordered immediate repairs and a massive cleanup that cost at least $2 million and required a team of district employees working 80-hour weeks for most of the summer.

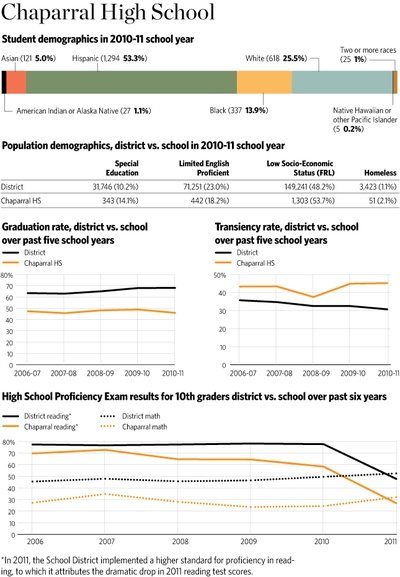

Chaparral’s official 2010 graduation rate stood at 48 percent, second lowest in the district, and it has some of the lowest test scores of any of the region’s public high schools, failing to demonstrate adequate yearly progress last year under the federal No Child Left Behind law.

For six years, the government has singled out Chaparral as needing improvement. Chaparral students who failed their eighth- and 10th-grade state proficiency exams in English and math have a less than a 10 percent chance of passing the 12th-grade proficiency tests.

Jones and the seven-member School Board designated Chaparral as one of the Clark County’s five “turnaround schools,” a U.S. Education Department designation that opens the doors for federal assistance. It also requires school districts to adopt one of four strategies to improve the troubled schools; Clark County’s choice was to transfer the school’s principal and half of its staff in return for federal grant money, in this case as much as $1 million in the first year.

Wilson, who spent three years as principal at Mesquite’s Virgin Valley High School, one of the district’s better-performing high schools, volunteered to be transferred to Chaparral to try to reverse its downward spiral. The son of a university education professor and an elementary school teacher, Wilson considers himself a turnaround specialist, a backslapping tactician who wants results, not excuses, before moving on to his next school. “Effective teaching, effective teaching, that’s all I give a damn about,” Wilson says.

•••

The managerial change announcement sparked a student protest at the high school in March. The teenagers liked many of their teachers and said they thought this was a personal attack on the Chaparral community.

Teens chanted, sang songs and raised their fists in solidarity for their principal, Kevin McPartlin, and teachers who were being transferred to other schools. Several teachers held protest signs: “Why Should We Have To Suffer?” and “Why Would You Do This To Us?”

Jones embraced the rally, telling Chaparral and district administrators to let it continue in a community where the systemwide high school graduation stood at 50 percent. “If only 50 percent of (our students) are graduating, I would have been protesting at the flagpole,” Jones recently said.

“I like your teachers, too,” Jones told student representatives in a private meeting later. “But I like you more, and actually, my business is about you.

“Right now, 50 percent of the kids in this school don’t graduate high school. Is that acceptable to you? Think about that. Right now, some of the friends that you’re with aren’t going to graduate. Is that OK? That’s unacceptable to me. I think you guys ought to kick all of us out.”

The arrival of the 48-year-old Wilson, a burly, ex-high school jock who liked to get into the occasional fight as a teen, was greeted with derision. Teachers ignored him. Others flashed nasty looks. He heard hisses and verbal sniping from educators who feared for their jobs at the school. Wilson says he found in McPartlin a young principal who was doing his best to fix the school’s academic troubles, but in many cases had a staff who lacked the will or the ability to do what was needed.

English teacher David Winkler, an eight-year veteran of the school who was retained by Wilson, spoke up in March against the changes. “What I do hope will happen is the people will come to their senses and find a spot for all of us and realize we’re educators who really care about our kids,” Winkler said at the time. Now, he’s equally circumspect, saying he’s concerned for the morale of some returning teachers having to adjust to a new management style. “My perception is the administration is not just talking in terms of reorganization but also in terms of being more successful.”

When Wilson met with those two dozen students on that recent morning, he took them on a tour of the refurbished campus. When they walked into the restroom, jaws dropped. Tiles had been scoured, new glass installed in mirrors, toilet seats replaced. As they opened stalls, the students erupted in laughter and giggles, and literally hopped and jumped in celebration.

“I knew there were a lot of changes, a lot of improvements,” said Donald Way, a junior. “It’s a better environment for us.”

Xavian Young, a senior, said: “The whole school’s different. It’s a different school.”

School administrators selected the students for the tour because they were leaders among their peers. There was a football player, some members of the student council, and some who were known for their ease in making friends. Wilson thought if he could reach them, they would help set a positive attitude for the first months of the Wilson era.

And he put them through a series of drills to illustrate the plight of their classmates.

He asked 10 to stand at the front of a classroom, then told half of them to sit down. Expect almost that percentage of students — 45 percent — to come and go during the year, he said. The school has a high transiency rate because the economy.

“This next number sickens me,” Wilson said, asking seven of the 10 to take their seats. “By the end of the senior year at Chaparral High School, that’s how many kids are graduating. That’s it.”

Wilson expects to change that.

•••

Chaparral was once a high-performing high school in the Las Vegas Valley, filled with middle-class children of casino industry workers and public employees.

Many of its graduates became doctors, lawyers, engineers, casino executives, professors and teachers.

The development of suburban Green Valley in the late 1980s and the opening in 1991 of the high school that bears its name lured away many of Chaparral’s families. As happened nationwide, white flight led to declining property values and an influx of poorer families.

Veteran teachers left the school for newer schools, where they had access to better classroom resources and a chance to teach some of the sharpest youngsters. In many cases, they were replaced at Chaparral and similar schools by less-experienced educators. Test scores declined.

Educators cite research showing that children raised in poverty begin school two years developmentally behind their more affluent classmates. Many never catch up. Although the School District’s official graduation rate for the school was 48 percent last year, Wilson’s analysis places the number closer to 28 percent when adjusted for students who had disappeared from the school. The numbers were even lower among boys, particularly blacks and Hispanics.

“That’s it. That’s why I’m here,” Wilson says of the dismal graduation rate. “There isn’t any other reason. The reason I’m here is I graduate kids. It’s not a hope. It’s not a dream. It’s the expectation.”

McPartlin is unapologetic about his reign.

“I appreciate your understanding that Chaparral was making gains before it became a Turn-Around School,” McPartlin wrote in an email after declining to be interviewed. His email included statistics reflecting academic gains and student growth during his tenure. “I believe the fact that Mr. Wilson hired the full 50 percent of the previous staff back, and would have loved to keep more, speaks volumes about the quality of the Chaparral family before this change occurred.”

Today McPartlin is principal at Arbor View High School in northwest Las Vegas.

Jones offered a nuanced analysis of McPartlin’s five-year tenure at Chaparral, calling him a “good guy” and crediting him for some successes but not enough, saying the school needed to be fixed faster. “I need someone who is going to be a lot more aggressive,” Jones said. “I didn’t feel like he was going to be strong enough to turn that school around.

McPartlin’s “approach was to say, ‘Hey, we’re making progress, slowly over time, and by Year Three we think we’ll be there.’ That’s too slow. That’s three classes that have walked across that (graduation) stage while you’re waiting to turn it around.”

•••

For some, Wilson is an acquired taste, an ebullient backslapper who fist bumps every teen he meets. He has read hundreds of studies about student performance and has heard the arguments for and against the reform initiatives of the day. He believes he hired strong teachers and assistant principals who will relentlessly work to turn around the troubled school.

“We will put in strong teachers who are good with content knowledge and behavior … target those kids in need of additional help and put the right adults with them and be a cheerleader and follow up with them,” he says.

His plan has each student meeting with a counselor every quarter. Those who fail two or more classes in a quarter will get significant attention, and Wilson will track the results. “The data assessments are going to be stronger than what is found in any other high school in Clark County, to date. We’ll know this is who they are, where they’re at, what they need. We will track them with fresh data every two weeks.”

He thinks 98 percent of his teachers will succeed, and he says he will watch them closely, particularly during the first three weeks of school: He and his team of four assistant principals and a dean of behavior will push to establish a new campus culture, one that reverses the benign neglect that he says plagued the school.

They will teach from bell to bell, assign student-driven work that challenges the best students and reaches the weakest. He and his staff will get to know every one of the school’s 2,250 students by name, and will monitor the biweekly data of student performance and will have an easily accessible file for every Chaparral student. Administrators will be in classrooms every day monitoring student and teacher performance, and the staff will meet in teams, planning and coordinating instructional efforts.

The best teachers will coach colleagues. A full assessment of teacher performance will be offered at the close of both semesters.

Through it all, Wilson’s message is clear for new and returning teachers: “If you’re not good enough, we’ll provide you with three weeks of administrative assistance, and then we’ll have you transferred.”

Chaparral High School has seen better days.

Once among the top performing schools in the Clark County School District, Chaparral High is undergoing changes to counter dismal test scores and the lowest graduation rate in the district.

The campus located near East Flamingo Road and U.S. 95 is one of five turnaround schools not meeting the expectations outlined in No Child Left Behind.

Chaparral is now looking to clean up its reputation, touching every aspect of the school from restrooms to test scores.

Changes weren’t received well by students who openly protested the cuts to faculty and the new order that banned the use of cell phones and music players during the school day.

Under stricter rules, tardy students are locked out of classrooms, bathroom breaks during class time aren’t allowed and the lunch hour was pushed back to 1:40 p.m.

Superintendent Dwight Jones told students he’s not settling for half successes.

“Right now, 50 percent of the kids in this school don’t graduate high school. Is that acceptable to you? Think about that. Right now, some of the friends that you’re with aren’t going to graduate. Is that OK? That’s unacceptable to me. I think you guys ought to kick all of us out.”

- Year built:

- 1971

- Mascot:

- Cowboys

- Principal (Year Hired):

- David Wilson (2011)

- Enrollment:

- Approximately 2,250

- School Report Card:

- 2010-2011

Compiled by Gregan Wingert

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy