Chris Morris / Special to the Sun

Sunday, Aug. 28, 2011 | 2 a.m.

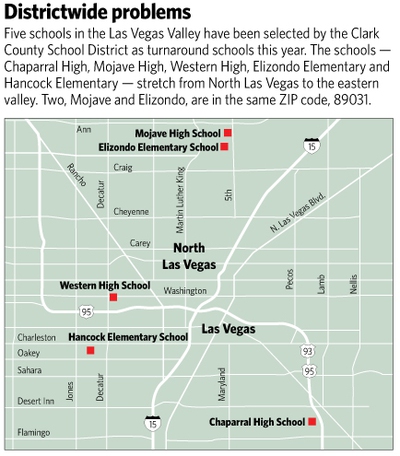

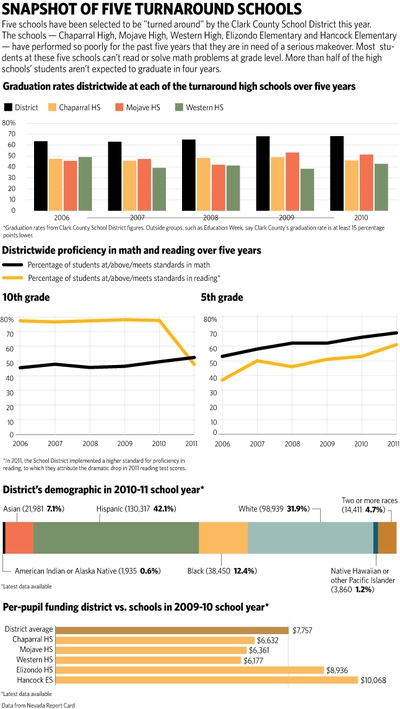

Three high schools and two elementary schools in the Clark County School District have been designated as needing help to turn around poor performance. Starting today, the Sun, with the cooperation of the district, will chart their progress.

Also today, in partnership with the Sun, KSNV Channel 3 launches its coverage of “The Turnaround: Inside Clark County Schools” at 11 p.m. Sunday. News 3 anchor Jessica Moore will explain the project and introduce the five leaders of the turnaround schools. Starting Monday, coverage moves to “News 3 Nightly at 6,” focusing on one school each day. These schools will also be featured by the Sun throughout the week.

- Monday: Principal David Wilson’s effort to restore “Chaparral Pride.”

- Tuesday: The new “relationship-builder” at Mojave High, Principal Antonio Rael.

- Wednesday: How Western High Principal Neddy Alvarez will pass on lessons learned from her father.

- Thursday/Friday: Where many principals focus on teachers and students, Elizondo Elementary’s Keith France says his focus will be on parents. When it comes to her staff, Hancock Elementary Principal Jerre Moore says, “I don’t have three months for them to get it.”

Round-table Discussion: Turnaround Schools

School District leaders Dwight Jones, Superintendent; Pedro Martinez, Deputy Superintendent of Instruction; Florence Barker, Turnaround Leader; and Carolyn Edwards, School Board President; sit down with reporters Dave Berns and Paul Takahashi to discuss turnaround schools, challenges of the upcoming school year and the Sun's ongoing project, "The Turnaround: Inside Clark County Schools."

Dawn is still an hour away and Dwight Jones is in his office, running on four hours of sleep. There’s not enough time in the day, he says, to address all the problems facing the Clark County School District.

So much to do. So much at stake. And as Jones begins his first full school year as superintendent, he sounds overwhelmed.

“I believe we’ve got to change this whole system,” Jones would say later, his eyes sunken but determined. “We’ve got thousands of kids who are in harm’s way right now ... We’re working as fast as we can to save some of them.”

The School District’s reputation is well known: the fifth-largest and among the poorest performing in the country. Last fall, Jones, Colorado’s education commissioner, was recruited to take charge of the district and correct its course.

It will take some time, he says. You can’t turn an aircraft carrier around on a dime. But there are litmus tests to gauge results by the end of the school year.

Those tests are three high schools and two elementary schools, deemed to be performing so poorly that they’ve been singled out as turnaround schools, in need of makeovers aimed at nurturing success where failure has been too familiar a face.

The schools — Elizondo Elementary, Hancock Elementary, Chaparral High, Mojave High and Western High — have been defined as failing under No Child Left Behind, the federal law to compel better student performance. Most students at these five schools can’t read or solve math problems at grade level. More than half of the high schools’ students aren’t expected to graduate in four years.

The unprecedented turnaround effort started last spring. Principals and teachers have been replaced, pep talks delivered, curricula revised, campuses repaired and scrubbed clean.

Now the hard part begins. School starts Monday.

So too begins the Sun’s yearlong project to chronicle the triumphs and successes, the trials and tribulations of the School District’s great experiment with education in Las Vegas: the turnaround.

•••

Over the past two decades, when Clark County was the fastest growing metropolitan region in the country, the School District was too busy opening schools to give adequate attention to the quality of what was being taught, and how it was being taught, inside. Indeed, the district would emerge from its building boom as the fifth largest in the country, at its peak opening a school at a rate of once a month.

At the same time, student demographics were changing in Clark County. More students were coming from historically disadvantaged, poor and minority backgrounds. The number of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunches jumped more than 20 percentage points from 1990 to 2010. In 2006, the number of Hispanic students surpassed the number of white students for the first time.

With classroom resources stretched thin and parental involvement waning, students suffered. Test scores dropped, graduation rates fell and the state’s education ranking plunged.

The district “got so focused on taking care of growth, it lost focus of its real mission,” Jones said. “The mission was building schools, staffing schools and opening schools. The mission was not focused on what is actually happening in the schools.”

Circumstances worsened in the Great Recession.

The housing bubble popped, trapping hundreds of thousands of Las Vegans in underwater homes. Unemployment in the largely two-industry town of gaming and construction rose to double digits and lingered there. The city of glitter lost its luster and growth went flat.

During this time, Superintendent Walt Rulffes announced he would retire, and the search was launched for his successor.

In December, the School District hired Jones, who had earned a reputation in Colorado for shaking things up.

The time seemed ripe to address the deep problems facing education in Las Vegas.

Print Edition

The Las Vegas Sun print edition on Sunday, Aug. 28, 2011, featured coverage of the launch of the yearlong project, "The Turnaround: Inside Clark County Schools," throughout the paper. See what the coverage looked like in print at lasvegassun.com/turnaround_print.

» Click here to download .pdf of Sunday's front page.

In just nine months, Jones — a former turnaround principal from Wichita, Kan. — brought about a flurry of systemic changes to Las Vegas, from district reorganization to new initiatives to measure student achievement and boost graduation rates.

Those changes were ambitious and bold — the kind that can draw high praise from some and harsh condemnation from others. When the district announced it was restructuring the five turnaround schools, hundreds of Chaparral students protested the decision to remove its popular principal and favorite teachers.

The students were angry, resentful of a district that in their eyes punished teachers for their low test scores. The district didn’t see it that way; in its view, teachers were being held accountable for their students’ academics.

A few days later, Jones sat down with about 15 members of the Chaparral student council, and explained to them the turnaround. The restructuring was part of an effort by the School District to secure $8.7 million in federal stimulus money to make the troubled schools better, he said.

Nevada received about $20 million from the School Improvement Grant program, one of eight states to do so this year. The three-year grant targets schools identified under guidelines enacted during the George W. Bush administration as “persistently lowest achieving.” In other words, schools with low graduation rates and/or test scores.

To get the grant, the School District had to adopt one of Washington’s four dramatic recipes for change: Close the school, cutting its losses and starting anew somewhere else; reopen a failing school as a charter school; recruit new principals and institute reforms starting at the top; or the turnaround model.

The School District went with the fourth option that called for replacing principals with more than three years of experience and making all the staff reapply for their positions. Administrators could not rehire more than 50 percent of the existing staff.

The Chaparral students “felt like this was an attack on their teachers,” Jones said. “I said, ‘Yeah, I get that. I like your teachers, too. But I like you more, and actually, my business is about you.’

“ ‘Right now, 50 percent of the kids in this school don’t graduate high school,’ ” Jones added. “I asked them, ‘Is that acceptable to you?’ ”

•••

The School District first applied for the School Improvement Grant in the 2009-10 school year. However, it was a tepid effort, said Pedro Martinez, Clark County deputy superintendent of instruction. At the time, he was Washoe County School District’s deputy superintendent.

Washoe sent in seven school applications, but Clark County — the largest district in the state — applied for and received funding for just two schools: Rancho High and Kit Carson Elementary.

Clark County School District’s reform efforts didn’t go as far either, Martinez said. The district under Rulffes, for instance, replaced Rancho’s principal but kept the staff. Although both Kit Carson and Rancho improved their test scores after one year, the district could have helped more of its struggling schools receive federal funding, Martinez said.

Indeed, Nevada frequently turns a cold shoulder to federal money, maybe because of its libertarian streak.

“We’re not very aggressive in applying for federal grants,” Martinez said. “If we ignore this, that’s at our own peril, because we’re going to be left behind.”

So after Jones recruited Martinez, they sought more funding from the School Improvement Grant, which demands “real reforms,” Martinez said.

In other words, this wouldn’t be a rehash of what had been tried before. “We know what those results have been: We’re last in graduation, we have some of the highest remediation rates and we have some of the lowest college-going rates in the country,” Martinez said. “We’re tired of seeing that.”

•••

For the second round of grant applications, the School District under Jones’ leadership selected five schools from a few dozen low-performing schools for turnaround.

Of those schools, four — Chaparral, Hancock, Mojave and Western — received the funds. Elizondo, which didn’t receive the federal dollars, will still be considered a turnaround school, with the School District footing the bill.

Because the principals at Hancock and Western have been at their respective schools for less than three years, they were allowed to stay. Principals at the other schools were replaced, but big staff changes occurred at all the schools.

Most of the grant money will go toward higher salaries and benefits for educators at each — combat pay, as it were, to entice people to work at these low-performing schools.

Principals were given $5,000 signing bonuses; teachers, $1,750, and support staff, $500 for the first year of the grant. In the next two years, teachers would be paid more if their students do better on tests.

In return, these schools must show vast improvements in test scores, discipline issues and parental involvement starting this year. Administrators are given more flexibility over their schools’ budgets, scheduling and staffing, but they may be transferred at any time if they don’t “perform,” or deliver results.

“Adult success will be determined by the success of kids,” Jones said. “It seems easy to say, but that’s quite a departure (for the district). If kids’ success is most important, then evaluations and other accountability measures have to mimic that. Building a performance framework is a lot more aligned to true reform.”

Teachers will be paid more at these schools in large part because the school day will be longer. High school students will be in school up to 20 minutes longer, and elementary school students about an hour longer.

Each school will also offer a new curriculum from a math and reading academy for college and career preparation courses.

At Chaparral, students will be exposed to a variety of postsecondary options at its college and career preparatory academy. At Mojave and Western, students can attend an engineering, math and science academy. At Hancock and Elizondo, the emphasis will be on reading and writing.

Even the teachers and administrators will be learning this year.

Principals attended a weeklong “turnaround” conference this summer at the University of Virginia that focused on how to engage and motivate teachers, staff and students. At workshops, the principals examined school-turnaround case studies and some involving private companies.

Throughout the year, teachers will get training and support from education companies such as Pearson, Teachscape and Edison. They will have additional time during the week to plan a coordinated curriculum with fellow teachers across grade levels and disciplines.

“If the only strategy we did was change out the adults, I’d say that probably isn’t a very good strategy. That alone won’t get us the results we want,” Jones said. “We’ve tried to recruit some of the best and brightest teachers … really focusing on training and having the right tools in place and analyzing data. There are a lot of things changing.”

•••

The motive to turn around schools transcends improving the classroom performance of students, Martinez said. It has everything to do with his favorite quote from Education Secretary Arne Duncan:

“You cannot have a strong, healthy community if you have a broken school.”

Driving around Las Vegas, Martinez said he sees broken schools and broken communities. There are homes wrecked by the recession, two or three families living under the same roof and parents scraping together a livelihood by working multiple shifts and jobs.

To survive this recession, Las Vegas needs to diversify its economy, Martinez said. That requires a solid education, in growing fields such as science, engineering, health care and technology.

That won’t happen the way things are now, he said. Las Vegas has an education crisis — too many kids are in harm’s way, Martinez said.

“If you have individuals who are not being prepared to have good-paying jobs, go to college and get into postsecondary education, then frankly, I think it just perpetuates poverty and unemployment,” he said. “As we make these reforms and kids are coming up better prepared, I think it’s going to transform this community.”

So the project that is causing Dwight Jones to wake up before dawn may also lead to a community turnaround.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy