Cathleen Allison / AP

Gov. Brian Sandoval, shown here Jan. 3 at his inauguration, has unveiled a plan that will call for “shared sacrifice” to balance the state’s budget.

Sunday, Jan. 23, 2011 | 2:01 a.m.

Related story

Sun coverage

Sun archives

- Sandoval eyes students’ wallets to help close deficit (1-7-2011)

- Increasingly worried liberals seek pushback on Sandoval budget (1-21-2011)

- Sandoval proposes 5 percent pay cut, no furlough for state workers (1-12-2011)

- Gov. Brian Sandoval’s quest: Blocking a tax hike (1-9-2011)

- Sandoval suggests ‘significantly higher’ fees for higher ed students (1-5-2011)

- Economists say Nevada’s budget problems not going away anytime soon (1-5-2011)

- Brian Sandoval all talk and no facts for now (12-30-2010)

- Sandoval increasingly isolated in his anti-tax stance (12-29-2010)

- State has upper hand in budget turf war (12-27-2010)

- Sandoval to build own budget (12-22-2010)

- Panels propose ideas to squeeze state budget (12-4-2010)

- Sandoval budget assumes 10 percent cut to state, higher ed and furloughs (12-2-2010)

- Polished knife still cuts deep into state’s budget (11-28-2010)

- Expect Sandoval to flex his newfound political capital on his anti-tax pledge (11-10-2010)

- Let Sandoval take heat for budget, Democrats say (11-5-2010)

- University system snubs governor, won’t submit budget with cuts (10-28-2010)

- State’s budget woes could end programs targeting seniors (10-27-2010)

- Home assistance for disabled among services on budget chopping block (10-21-10)

- $2.5 billion state budget deficit: ‘Best-case scenario’ (4-23-2010)

On Monday, Gov. Brian Sandoval will deliver his first State of the State address.

It promises to be equal parts optimistic vision statement — the new governor has promised Nevada will return to its former glory within three years — and tacit telling of hard truths — he will simultaneously present a budget that he intends to balance without new taxes and despite a $2.2 billion deficit to maintain current services. This, he says, will be accomplished through “shared sacrifice.”

Whether Sandoval acknowledges it or not Monday night, the path from the hard present to the hopeful future is unclear. What is evident though is that moving Nevada forward will be more difficult than it would have been even two years ago, when the Legislature last convened in regular session to confront a daunting deficit.

In the two years that have passed, unemployment has risen from 10 percent to 14.5 percent. And growth, a well-worn crutch leaned upon for funding, is gone as our population is shrinking. Add to that other indicators — declining wealth, increasing poverty, fewer teachers per student — and it’s clear that Sandoval has fewer resources to draw upon to fulfill his promise that by 2014 “Nevada will be Nevada again.”

Of course, even during the best of times Nevada struggled with social problems and substandard educational outcomes, partly the result of its image as a destination of last resort and partly a failure of leadership. Growth was so rapid and unrelenting that institutions — government entities and private nonprofit groups alike — struggled to keep pace and develop into mature and effective organizations.

Until as recently as 2007, that didn’t matter, or it didn’t matter as much.

During the boom, Nevadans, from the executive suites of the Strip to the suburbs with their inflated home prices, were building tremendous wealth. There were fights about what to fund and who should pay, but as long as Reno and Las Vegas kept stretching into the desert, there were resources.

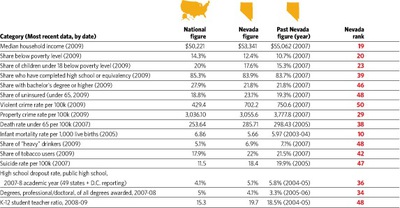

Now, the state is left with largely the same problems — in some cases they’re a little worse, in some cases a little better (see accompanying chart). Employment, hours worked, wages and wealth have all plummeted. This has created surging demand for services such as Medicaid and food stamps, as government’s ability to deal with the same old problems, let alone the new ones, is diminished.

•••

Sandoval has declined to preview his plan for solving the deficit. But some of the contours of his budget have emerged in the past few weeks:

• He will not, at any cost, raise taxes or fees.

This is more than a campaign slogan to curry favor with the conservative base but rather, he says, a philosophy for keeping the economy on life support as he works to bring new industry to the state.

• Local governments, state employees and college students will likely bear the brunt of spending cuts.

State worker furloughs implemented last session will be replaced by an across-the-board 5 percent salary cut. And universities and community colleges could be given the power to increase tuition, and keep the additional revenue, to offset cuts in state funding.

• He is expected to shift revenue from city and county coffers to the state general fund to offset potentially painful funding reductions.

His advisers are selling this as a more unified approach to government spending, arguing the divisions between state, county and local government are largely meaningless to the average taxpayer.

• Sandoval also will be picking and choosing from proposed 10 percent cuts submitted by state agencies under the administration of Gov. Jim Gibbons.

Sandoval’s message of “shared sacrifice” can be summed up this way: State agencies, and by extension those who rely on state services, must sacrifice so that businesses don’t endure tax increases. This, he argues, will make the state appealing to businesses looking to move.

But some evidence suggests cutting government spending could be a bigger drag on the economy than raising taxes on business.

Elliott Parker, an economist at UNR, said both spending cuts and tax increases have a negative effect on a state’s gross domestic product during times of recession. But, in particular, a cut in existing government spending is the worse alternative.

“There’s a big difference between doing something in a recession and doing something in a boom,” he said. “When the economy is going great guns, you can cut the government sector and pretty easily make up the difference in the overall sector.”

Not so during a recession, he said.

Again, timing is everything. A misplaced tax increase could chase off private investment needed for recovery. But Nevada’s economy isn’t yet poised for recovery.

“We’re nowhere near recovery,” Parker said. “To the extent we’re stabilizing, we’re losing people as fast as we’re losing jobs. And the overall amount of spending in the economy is not recovering.”

That raises questions about Sandoval’s approach and the likelihood that it will lead the state to recovery as soon as promised.

Other economists, however, argue some government spending can be reduced in areas that don’t have as strong an effect on productivity — a fact Parker also acknowledges. For example, cutting spending on education, infrastructure and other areas in which the government or the economy receives something in return would hurt more than cutting spending on public employee retirement benefits.

“And on the tax side, it makes a big difference what taxes you raise,” said Tom Cargill, an economist at UNR. “So, it really depends on the composition of the expenditures and the composition of the taxes.”

Cutting spending on teacher salaries, for example, takes money out of the economy because teachers are likely to spend their earnings on goods and services here. By contrast, money that businesses save on lower taxes could land in their out-of-state headquarters.

Experts note that in addition to having a narrow economy — tourism and development — Nevada also has one of the narrowest tax structures.

The state has no personal or corporate income tax, no tax on services, and property taxes based on infrastructure replacement costs rather than market value. Nevada reaps no benefit from the value of a company’s intellectual property or the total capital stream of businesses with multiple-state holdings, such as hotels, casino and mining companies. Instead, the state taxes only on the value of buildings and equipment.

That’s problematic in the new world economy, experts warn.

“Even if Nevada is successful in diversifying its economy, under the current tax system, our tax base would remain narrower than our economic base because we would not be able to tax intangible property value, which is the largest component of value for many firms,” a recent study by UNR Center for Regional Studies found. “Our 21st century economy would continue to be assessed by 19th century measures.”

•••

Although there are sharp lines of disagreement over who should pay to fund government and how much, there’s less discord over things the state needs to improve its fortunes.

State leaders have for years agreed it should begin with a better education system.

They also agree that giving more control to schools, principals and teachers will raise student achievement and create a laboratory for education innovation. Sandoval, teachers union leaders and legislators of both parties have called for such changes to Nevada’s schools, which nationally have student-teacher ratios that rank 48th and among the lowest graduation rates and results on standardized test scores.

But the issue reveals where rhetoric and reality have parted ways in recent years.

The state set aside $100 million — money that flowed into state coffers in 2005 — to create pilot programs driven by front-line educators. Initially, it paid for things such as tutoring, discipline specialists and English-language instructors. If successful, they could be replicated elsewhere.

“I feel like we made steady gains in student achievement” under the program, said Keith Rheault, Nevada superintendent of schools. “Teachers and principals took ownership of the programs. It was some of the best money we ever spent.”

Then came the Great Recession. When Gibbons and lawmakers set about slashing the budget, the money to spur innovation in schools was among the first cuts.

Higher education, which experts say is a key driver to economic diversification here, was also hit, losing 700 employees, a drop of 5.5 percent from 2008. About 35 programs, degrees and academic centers have been eliminated or are likely to be.

Among the programs that have been eliminated: educational leadership.

The experience of the past two years underscores why talk of bright futures must turn to how the state improves fundamental services such as education.

It’s hard to sell CEOs on a state when you can’t assure them that their children and their employees’ children will receive a good education.

“If we do not close educational attainment gaps, nothing else will attract business,” said Robert Lang, director of Brookings Mountain West, a public policy think tank at UNLV.

“At some point we are just going to have to invest in our own future and say it’s in all our best interests to spend the money,” said Jeremy Aguero, principal of the consulting firm Applied Analysis.

Sandoval has said the state can improve its education system without additional money.

In response to Friday’s news that the state’s unemployment rate had inched higher, Sandoval cited it as a reason “why I’ve said we cannot burden struggling businesses with tax increases ... We must allow sunsetting taxes to expire at the end of June and provide businesses the environment in which to begin hiring again.”

Under Sandoval’s budget, Nevada’s largest businesses will see their payroll taxes drop to pre-2009 levels. The sales tax the average Nevadan pays on goods will also go down.

•••

It would be easy to point to the crisis and say the governor and Legislature are finally going to get serious about solving the state’s long-term social and educational problems and address a system of taxation that will lead to structural budget deficits for as far as the eye can see.

Lawmakers in charge of the budget two years ago acknowledge that they relied on short-term fixes, but deny it was political expediency. Rather, a stubborn and disengaged governor and the need to override threatened vetoes derailed their ability to make lasting changes.

“While temporary fixes are difficult, permanent fixes are near impossible without a great deal of work and consensus,” former Assembly Speaker Barbara Buckley, D-Las Vegas, said.

Barbara Buckley

Still, some economists say that in a crisis short-term fixes are about all a state can do, especially in a state such as Nevada that is dependent on consumer spending and the national economy to fund its government.

Some economists, those who adhere to the Keynesian school of thought, think government spending should be maintained as governments are the only entities capable of spending in a recession.

But that line of economic thinking often gets caught up in politics. “Instead of people staying rational, they say ‘that’s government spending and that’s wrong by definition,’ ” says John Restrepo, an economist and principal of Restrepo Consulting Group. “That’s how politicized things are.”

Although the governor and lawmakers may be capable of only short-term fixes in a crisis, they should also be laying the groundwork for a recovery, experts say.

However, seasoned observers, having watched the Nevada Legislature kick the can down the proverbial road session after session, believe the governor and lawmakers will likely take the path of least resistance.

This in turn creates space, however, for elected officials to step up to the lonely, quiet stage, and go big.

Sun reporters David McGrath Schwartz, J. Patrick Coolican and Delen Goldberg contributed to this story.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy