Once dubbed “Scarlett” for her dramatic and determined efforts to keep Southern Nevada in water, Pat Mulroy stands in a replica of a water pipe at Las Vegas Springs Preserve.

Sunday, June 8, 2008 | 2 a.m.

The men who manage urban water districts in the West tend to come out of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Who better to understand how and where Western water is taken from the Colorado River?

Special Sun Series: Quenching Las Vegas' Thirst

Beyond the Sun

They are not fazed that people consider them nuts for having proposed such a system of dams, reservoirs and open-air canals to deliver water across blazing deserts.

To explain why their system was built that way, Reclamation veterans will point to the tangled evolution of the Colorado Compact, their “Magna Carta,” their “constitution.”

After that, they will invite you to penetrate the bulging casebook of resolved water feuds known as “the law of the river.”

“It’s not a perfect system,” they will say, “but it works.”

“It’s not a perfect system, but it’s better than no system.”

These men even have a nickname: “The water buffaloes.”

But when Pat Mulroy took over as general manager of the Las Vegas Valley Water District in 1989, she was not a man, not from Reclamation, not even particularly experienced in water.

Nobody accused her of being a buffalo.

Her reaction to the Colorado Compact and its water delivery system, which sends the least water to the city closest to the river’s largest reservoir, earned her a different nickname entirely. “Scarlett.”

For those unfamiliar with “Gone With the Wind,” Scarlett is the ruthless, scheming, tough, histrionic and beautiful one who thrusts the turnips in the air and cries, “As God is my witness, I will never be hungry again!”

Mulroy’s vow: Las Vegas would never be thirsty again.

• • •

When Clark County Manager Richard Bunker first interviewed Pat Mulroy for a general administrative job in 1978, she was 25, exotic, blond and smart. A German-born daughter of an American father and a German mother, she was working at UNLV trying to finance a master’s degree in German literature at Stanford University. She hoped to eventually parlay this into a job with the State Department, but she also recalls that she was “in desperate need of a job.”

Diplomacy’s loss was Bunker’s gain. As she sharpened her pencils and found her parking spot at the Clark County manager’s office in 1978, she realized this was no ordinary administrative job. Bunker was furiously fighting off annexation of the Strip by the city of Las Vegas. The city itself was still so overtly a mob town that, as Mulroy recalls it, “you’d look up and Tony Spilotro would be standing over your desk. It was wild.”

Mulroy was so capable that Bunker quickly promoted her to lobbyist for Clark County, working the halls of the Nevada Legislature in Carson City. She drafted and then politically finessed legislation creating the public administrator’s office. (If you die intestate in Clark County, your heirs will find out what this office does.) This was most definitely not wild, but it taught her how to turn ideas into laws.

Not two full years after starting work with Bunker, it was over. Returning from a German holiday in January 1979, she learned from the passenger next to her that her mentor had just been appointed to the Gaming Control Board. “I landed and went, ‘Gee, I wonder if I still have a job?’ ”

She did, a number of them, but Bunker hadn’t spotted the job that would define her yet. By 1985, after a series of turnstile administrative positions, she landed as deputy general manager in charge of administration at the Las Vegas Valley Water District. Four years later, the district was looking for a new general manager.

As weighty as the deputy title sounds, it was in no way an obvious steppingstone to the general manager’s job. Administrators administrate. Water managers fight to keep their regions in water.

But Bunker saw steel and rare competence in Pat Mulroy, according to Mulroy, qualities that she didn’t even see in herself. He pushed her to apply for the top job.

Now, the logical candidate in terms of experience was not only a water buffalo but head buffalo, former Reclamation Commissioner Bob Broadbent.

Bunker, however, had a water pedigree to top that. He came from three generations of Southern Nevada Mormon irrigation farmers and renowned city burghers. One uncle had been among the U.S. senators to get Henderson hooked up to Lake Mead, another as a state assemblyman had tackled the crisis when casino wells threatened to cave in the ground beneath their golf courses. His father had led the formation of the Las Vegas Valley Water District.

By this point, Bunker himself was such an effective gaming lobbyist he all but spoke for the Strip. He understood, from the water mains upward, what was unfolding in a town that was about to give rise to the megaresort.

The man who as county manager had chosen fire chiefs and city planners did not want a buffalo running the Las Vegas Valley Water District. A buffalo would passively allow Las Vegas’ potential to be capped by its allocation from the Colorado River. A buffalo would be a true believer in the Colorado Compact, the treaty behind the building of Hoover Dam and Lake Mead and what Bunker regarded as the 1922 selling out of Las Vegas by Northern Nevada.

No, Bunker wanted Mulroy, so he did what came most naturally to him. He lobbied her.

At first she resisted. “Richard talked me into it,” Mulroy recalls. “He talked at me like a Dutch uncle. It took a while.”

The vote was 6-1 to appoint her general manager of the district. Clark County Commissioner Jay Bingham cast the dissenting vote. He said he didn’t think she was tough enough.

He may be the last person ever to hold that view.

• • •

As Mulroy took over the job, at first on an interim basis, even Bunker was not prepared for her daring.

She abhorred waste. The Las Vegas she inherited epitomized it. Rep. Shelley Berkley was working at the Sands when she first noticed the Water District’s new general manager. Berkley still shakes her head on recalling walking into a hotel conference room and seeing Mulroy berating some of the biggest names in town on water conservation.

If they didn’t come to the table, Mulroy went to them. “Probably the first confrontation was with Steve,” Mulroy says. Steve Wynn. “He was just about to build Treasure Island. We were in the midst of banning lakes and water features, so he calls me down to the Mirage and grilled me for two hours. I was very blunt with him. He said, ‘OK, what do I need to do?’ I said, ‘you need to use gray water’ ” — treated wastewater.

When she left his office, she carried a check for $100,000 for her conservation program and a dare to get every other casino owner to match it.

“The biggest of the big shots in town became her most vocal advocates,” Berkley says.

Ironically, the most egregious waste wasn’t from the casinos but from the seven local water companies serving the Las Vegas Basin: Boulder City, Henderson, North Las Vegas and so on.

“You got what you used,” Bunker recalls, “so everyone was using everything they could.” If they couldn’t use it, they dumped it into storm drains to protect their allocations.

Mulroy headed only one of the seven. She needed the other six to get with the program. Almost immediately, Mulroy was pressing them to pool their collective water under a new agency.

Bunker didn’t like her chances. “There was too much jealousy.”

But Mulroy had bait. Since the mid-1980s, the Las Vegas Valley Water District had been hunting Northern and Central Nevada for new water.

The notion of slipping ground water away from the rural counties promised an uproar. So quietly, very quietly, Vegas prospectors scoured the water audit bulletins of the state engineer, sizing up just how much ground water might be funneled out from beneath the rest of the Nevada to serve the Las Vegas Valley.

In October 1989, seven months into Mulroy’s tenure as general manager, the Las Vegas Valley Water District filed applications in Carson City for unclaimed ground water in 30 basins across four counties, a prospective haul of roughly 840,000 acre-feet of water — reportedly half the unclaimed water in Nevada.

State Sen. Virgil Getto, representative of the most water-rich counties targeted by Las Vegas, was on the Legislature’s Natural Resources Committee at the time and says he had no inkling of the plan until announcements of the filings began appearing in regional newspapers.

“I thought it was a dirty trick,” he says.

Mulroy would have a long road to travel to persuade the state engineer of Nevada to award Las Vegas the rights to pump even a fraction of it, but the applications meant that she had dibs on almost three times Las Vegas’ allotment from the Colorado River.

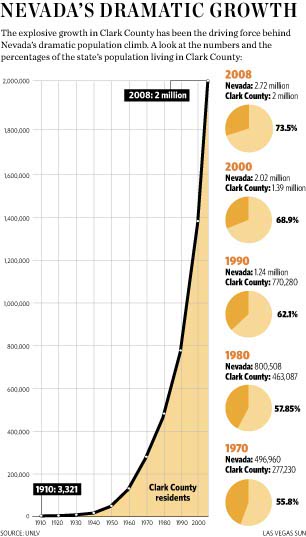

The rival water companies signed on to her plan. She had her new agency. After only three years in office, she was general manager not only of the Las Vegas Valley Water District, but also of a new regional supercooperative that comprised all seven water companies serving the then-835,000 residents of Clark County.

Once she had formed the Southern Nevada Water Authority in 1991, Mulroy wanted it to have a seat at the negotiating table with the six other states vying for water from the Colorado River. That job then lay with Nevada’s Colorado River Commission, a gubernatorial body that acted as water wholesaler to Las Vegas. Mulroy wanted her own appointees on it, people who understood the nitty-gritty of the water business, not grace and favor appointees by the governor.

She was sitting with Bunker in a Carson City restaurant when she mapped out a scheme to stud the governor’s commission with members of her staff.

In a bit of lobbying so successful that it surprised even Bunker, he got the idea past both the governor and the Legislature. As pure icing, by 1993 Bunker was on the river commission and by 1997, he was chairman of it.

The upshot: Northern Nevadans in Carson City might have settled for the smallest allocation from the Colorado River without any Southern Nevadans at the table in the 1920s.

That wouldn’t happen again.

• • •

Every triumph has a price tag. Assuming control over the local water districts of greater Las Vegas meant taking on their collective commitments to provide water to builders. “We were issuing ‘Will Serve’ letters left and right because we believed the myth we had all the water we’d ever need,” Mulroy says. And then one day, “we were sitting with our attorneys and saying, ‘We could have a problem.’ ”

Valentine’s Day 1991 was the day she refused to issue any more automatic “Will Serve” letters to developers. Her message: “Just because you own a piece of dirt doesn’t mean you have any water to go with it.”

From then on, they would have to commit to a project without a guarantee of water.

Logical policymakers might have controlled growth: 1991 was the year that poll after poll began showing residents in favor of slower, planned development.

History might read differently if Clark County residents voted as they polled and if a quarter or more of them weren’t transient.

But for those who stayed, as Steve Wynn went from his tropical lagoon to grand luxe phase, Las Vegas meant union catering jobs, cheap housing and low taxes.

Politicians who tilt at their constituents’ prosperity, or even more perilously at that of Las Vegas developers, should ask state Senate Minority Leader Dina Titus what happened after she proposed putting a ring around growth in Las Vegas. (She was ridiculed for mistaking Las Vegas for that communist enclave, Portland, Ore., then defeated for the governorship by Jim Gibbons.)

But Mulroy the lobbyist survived taking water guarantees away from builders by persuading them that their fortunes would come by taking risks.

This was her “New Paradigm,” and it went like this: With Mulroy at the water company and Bunker and a number of her staff on the river commission, Las Vegas would just keep building above and beyond the capacity of its river allocation.

It was a Las Vegas-sized dare. The logic: Defy the limits under Nevada’s Colorado River allocation. Dare the six other states on the Colorado River, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and its overseer the Interior secretary to not give them more water.

As the New Paradigm was unveiled in the press, a spokesman for Nevada’s Colorado River Commission even announced, “I say the federal government will never let Nevada go dry.”

The buffaloes put down their newspapers at the sheer nerve of it. There was only one place from which Nevada could get more Colorado River water. From California.

If they failed, they still had the ground water applications in rural Nevada.

• • •

Water is fuel. Without it, runaway growth across the Southwest would not be possible. To witness what cheap, federally subsidized water out of the Colorado River can do, look at the urbanization of Southern California, served by the Metropolitan Water District. Where once they grew oranges, lemons and limes, they now grow houses and freeways.

None of it was possible on the roughly 500,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water left over for Southern California cities after farmers took their 3.85 million-acre-foot share. It was possible only because California was enjoying water unclaimed by the four Northern Basin states — New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming and Utah. The Metropolitan Water District proved unmatched in the Lower Basin in glomming onto the surplus, as much as 800,000 acre-feet a year.

Combined with water drawn from the Sierra and another vast siphon from Sacramento to Los Angeles, the endless suburbs of Southern California were sucking up so much water that the runoff into the Pacific from lawn sprinklers and car washing alone reached an estimated 1 million acre-feet a year.

That was more than three times the Colorado River allocation for all of Southern Nevada, enough potable water for 2 million families, rushing through the gutters of greater Los Angeles and sweeping cigarette butts and motor oil out to sea.

Nevada wanted what California was wasting, so, Bunker says, “we had to do some surgery.”

In 1992, that meant lobbying new Clinton Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, the former governor of Arizona. Before taking office, Babbitt had been so opposed to Las Vegas’ ground-water applications that he had offered legal advice to rural Nevadans protesting the pipeline.

But like any Arizonan, Babbitt was also a natural ally of Las Vegas in any drive to curb California excess.

By the time Babbitt left office in 2001, Nevada had been so successful in bringing California’s draw on the river back into line that even President Bush’s new interior secretary adopted the Babbitt policy.

Mulroy did not stop there. Ferocious in search of water, she executed trades so complex that in 2006 even the state engineer’s panel of professional water people had trouble following them. A sample:

• She struck a massive water-banking deal with Arizona, paying Arizona to store unused water in its aquifer and allowing Las Vegas to withdraw the difference from Lake Mead.

• She bought up historic, pre-Colorado Compact water rights on the Virgin and Muddy rivers, both Colorado River tributaries.

• She moved with Arizona and California to have a reservoir built that will prevent Mexico from receiving more Colorado River water than it is allocated, and secured the right to draw some of the saved water from Lake Mead.

But the biggest, most potentially valuable supply of water in the Las Vegas water plan was still the vast pool underlying the Great Basin.

• • •

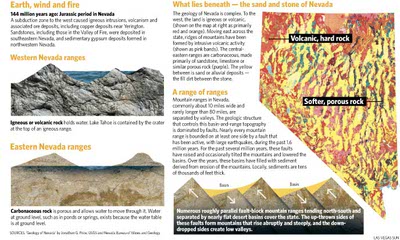

The Great Basin got its name because the region doesn’t drain to the sea. Extending from Death Valley to Salt Lake, it amounts to a 200,000-square-mile bowl engulfed by mountainous walls — the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade Range to the West and the Rocky Mountains and the Colorado Plateau to the East. It contains most of Nevada, a slice of Northern California, a small topping from Oregon and roughly half of Utah.

The topography is classic Western basin and range and, for all its beauty, it’s a prehistoric accident scene.

Nevada, from the Spanish for “snow-capped,” was named for its hundreds of ranges.

These were formed by the stretching of the continent until it ripped apart, tossing rock and earth into what is now a heroic network of north-south-running mountains and valleys.

As glaciers melted at the close of the Ice Age, the trapped store of ground water in the often porous jumble of rock underlying the area became the Great Basin “carbonate aquifer.”

In stark contrast to the way a massive tide of snowmelt from the Rockies courses toward the sea in the Colorado River, spring thaw in the dry ranges of the Great Basin is glugged up by plants, animals and people.

What life exists naturally aboveground, both in the hot desert to the south and in the cold desert to the north, depends on the state of the underground water table.

In “dry valleys,” the upward pressure of the carbonate aquifer sustains the springs feeding startling oases, even in the blazing deserts of Lincoln County.

In “wet valleys,” the aquifer’s pressure can make the desert seem suddenly lush. Snowmelt from the ranges drains into such highly saturated basins that it dances out of springs, then streams onto the valley floors. It can even shoot from newly drilled wells.

Just this kind of thing used to happen in Las Vegas before it pumped its local store of ground water so hard that a place whose name means “the meadows” became scrub.

Nothing terrifies the cold desert counties north of Las Vegas more than the prospect of seeing their valleys similarly denuded.

Over in the Sierra, the Los Angeles Aqueduct drained what was once Owens Lake so dry that by the 1970s, its parched alkaline playa was the source of routine dust storms behind the worst recorded particulate air pollution in U.S. history.

Owens Valley had once been a lake. By contrast, the basins at the heart of the Las Vegas pumping plan had mainly seasonal springs and streams.

In dry years, dust storms were common.

The minute that Mulroy’s applications for the Great Basin became public in October 1989, the protests were so thick that in no time “Scarlett” was being likened to another mythic figure, the man who inspired “Chinatown.”

Between 1989 and 1994, every major newspaper in the country had likened Mulroy’s project to that of the notorious William Mulholland, the Los Angeles water manager whose aqueduct had reduced the once lush Owens Valley to a dust bowl.

Some of the worst pain registered in Las Vegas itself, where biologists feared the loss of an international treasure. “The only other desert in the world with anything comparable to Nevada’s storied flora existed in Persia,” says College of Southern Nevada botanist David Charlet, “until the cradle of civilization sucked it dry.”

Among the more than 3,600 protests to Mulroy’s plan sent to the state engineer were ones from almost every agency in the Department of Interior except Reclamation.

To get her water, Mulroy would have to go through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management.

To top it off, no group took more passionate exception to Mulroy’s plan than the descendants of the very pioneers of the region. To rile a Utah Mormon, try describing the Great Basin aquifer as a Nevada “in-state resource.”

By February 1994, a chastened Mulroy had backed off the plan, so far that in an interview with the High Country News, she cheerfully quoted — and even appeared to concur with — critics that the Las Vegas pipeline was “the singularly most stupid idea anyone’s ever had.”

Then the dawn of the century brought drought.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy