Hydrogeologist Timothy Durbin was recruited by the Southern Nevada Water Authority in 2001 to help predict the effects of ground water pumping in the Great Basin Desert. The former U.S. Geological Survey employee found pumping could result in a significant drop in the area’s water table.

Sunday, June 29, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Special Sun Series: Quenching Las Vegas' Thirst

Reader poll

It was hydrologist John Bredehoeft, shown at his home in Sausalito, Calif., who first voiced opposition to the Las Vegas pumping plan in the 1980s when it was just an idea. Then, as now, he argued it amounts to ground water mining, which is illegal in Nevada. Las Vegas still maintains it needs the water to survive and grow.

Beyond the Sun

The raw glory of the Mojave and Great Basin deserts is difficult to imagine from the paved fantasyland of Las Vegas.

As the road wends north of the city, past sun-soaked bluffs into Pahranagat Valley, there is what looks like a river but are in fact four spring-fed lakes running for some 40 miles.

Audubon himself would weep at the birdlife working this watering spot on the Pacific flyway. Bald eagles ride the breezes. Herons skid across the water.

Proceed across huge desert valleys and the land rises. Yucca gives way to pine, the hot desert to cold, Paiute territory to Shoshone.

This is the land of nut gatherers.

Three hours into the drive north from the Las Vegas offices of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, there is no missing the entry to Spring Valley. Farms begin to dot the valley floor, alfalfa fields meld with bright green carpets of greasewood and rabbitbrush.

By the time Wheeler Peak appears, the conifers rival those of the Sierra. In Spring Valley, one type of cedar is thought unique on Earth. There are bats, owls, woodpeckers, rabbits, elk, mountain lions.

Yet throughout the Great Basin Desert, the fecundity persists on the slimmest of margins.

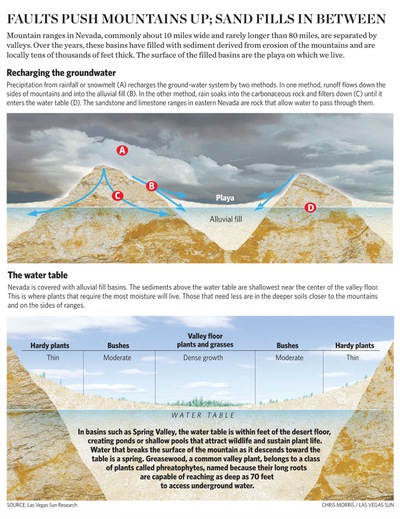

It survives because, after spring thaw, not all of the mountain snowmelt is immediately absorbed by the desert.

Rather, springs, creeks and ponds form, all held above ground by pressure from more water below.

This water below is the Great Basin aquifer, a vast pool dating back to the ice age.

There could be no more enticing prospect for a desert city like Las Vegas than these millions of sleeping gallons.

But if the aquifer is pumped too hard, the system of springs, streams and lakes supporting life above ground could disappear.

At issue, then, was could, and should Las Vegas attempt to get this water.

In considering a pipeline to tap the aquifer, Las Vegas calculated how much water flowed into the valleys of the Great Basin each year, then how much went legally unclaimed.

In 1989, Las Vegas filed applications with the state engineer for what was thought to be the rights to half the available water in Nevada — more than 800,000 acre-feet from some 30 valleys.

When, more than a decade later, the Southern Nevada Water Authority considered how to turn the massive block of claims into real water, the plan was pared down to six key valleys in Clark, Lincoln and White Pine counties, spanning the terrain north of Las Vegas, from hot desert to cold.

This time Las Vegas sought roughly 200,000 acre-feet a year of water, enough to serve a million people.

The pipeline length shrank from more than 1,000 miles to 285 miles.

It could always sprout arteries later.

As a next step, the state engineer would need to hold hearings in which Las Vegas would make its case for the water and protesters would appear with their objections.

The state engineer’s decisions would not come in a single finding. Rather, since 2002, he has been scrutinizing applications valley by valley, or several valleys at a time. Each green light he gives adds water to the pipeline.

One hearing over one valley had make-or-break status for the pipeline plan.

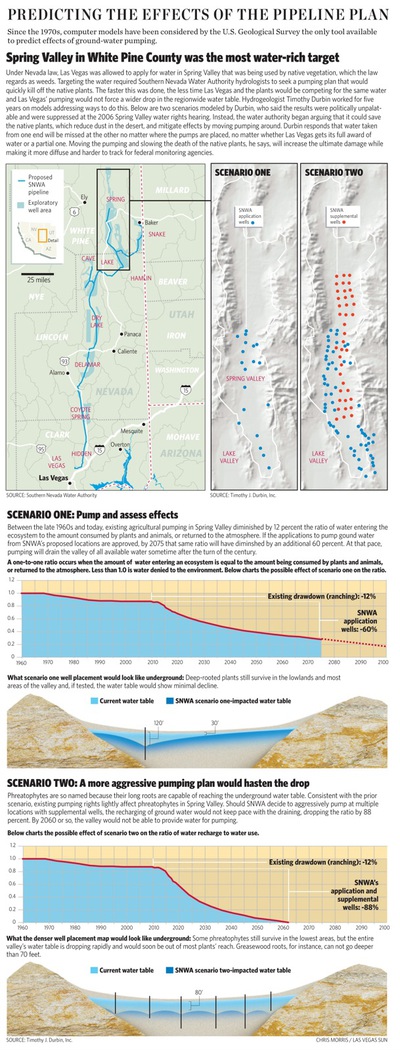

Of the 200,000 acre-feet of water a year sought by Las Vegas, roughly 90,000 acre-feet would ideally come from Spring Valley, one of the basins receiving spring snowmelt from the snow-studded queen of Nevada ranges, Wheeler Peak.

Las Vegas was seeking what it estimated to be all legally unclaimed water in Spring Valley.

The Spring Valley hearing began on Sept. 11, 2006. The two weeks of testimony that followed were most remarkable for what wasn’t said.

• • •

Making the case in 2006 that hot desert Nevada needed the cold desert’s water was not hard. Seventy percent of Nevadans lived in or around Las Vegas.

What was difficult was demonstrating the cold desert had water to spare.

Arguing that it didn’t would be the Princeton-educated eminence grise of American ground water, John Bredehoeft, whose title at the U.S. Geological Survey in the 1970s and ’80s was no less than Regional Hydrologist Responsible for Water Activities in the Eight Western States.

Bredehoeft had been aware of Las Vegas pipeline plan from its inception.

He never liked it.

Bredehoeft was going to appear at the Spring Valley hearing as an expert witness for rural communities protesting the Las Vegas pipeline.

As he explains it, there is no water to spare for Las Vegas without disrupting the equilibrium between water flowing in from snowmelt and water taken out every year by ranchers, plants and animals.

Las Vegas managed to insert itself into this equation because under Nevada water law, only some of the Great Basin’s traditional water users are legally entitled to it.

Towns are, farms are, mines are, but under increasingly antiquated definitions developed in the first half of the last century to do with “beneficial use,” most of the native flora isn’t.

Following this logic, water used by plants such as the cold desert’s signature shrub, greasewood, may be legally diverted hundreds of miles away to Las Vegas.

But by the time Las Vegas was going for greasewood’s share of Spring Valley’s water in 2006, the law of “beneficial use” was at loggerheads with a host of other modern laws protecting the environment.

Greasewood belongs to a class of plants called “phreatophytes,” named because their long roots are capable of reaching deep underground to access the water table.

As Bredehoeft sees it, if Las Vegas sinks its wells and the roots of the phreatophytes continue to chase the descending water table, that means Las Vegas won’t be taking the water from the greasewood but from storage in the aquifer.

“Taking water out of storage,” he says, “is mining.”

Mining ground water is illegal in Nevada.

Mine enough of it and the water table can drop for hundreds of miles around. Springs stop flowing, streams disappear, plants and animals dependent on them die.

So the logic goes: Target the phreatophytes whose water you intend to take, and don’t allow them to compete for water.

Pump hard. Kill them fast. Then let the system return to equilibrium so what water comes in from snowmelt equals what is taken out by Las Vegas pumps, and the water table doesn’t fall inexorably.

But this weeds-for-water logic becomes a problem when greasewood serves an important function above and beyond offering forage to deer and cattle.

Phreatophytes prevent dust storms.

Spring Valley sits at the foot of Mt. Wheeler. In 1986, then-Congressman Harry Reid led Wheeler’s transformation into Great Basin National Park, in no small part because of Spring Valley’s pristine air.

Without a high water table saturating the valley floor and the long roots of phreatophytes anchoring the soil, Spring Valley could become the kind of dust bowl created by Los Angeles after William Mulholland began pumping Owens Lake in 1913.

Once Los Angeles drained the lake in California’s high Sierra, it began taking Owens Valley ground water. By the 1980s, the wasteland created by Los Angeles had given dust a new common name.

The vile mix of fine sand, arsenic and assorted metals billowing out of Owens Valley became the single worst source of “particulate pollution” in the nation, registering at 23 times the level allowed by federal heath standards. It filled local emergency rooms with asthmatic children. It traveled hundreds of miles, clouding three national parks and repeatedly shutting down China Lake Naval Weapons Center.

Owens Valley was not the image the keepers of Nevada’s only national park wanted on their postcards.

Las Vegas found itself putting on two faces.

It was applying to the state engineer of Nevada to seize the greasewood’s share of Spring Valley’s water.

But in 2004, in seeking passage for the pipeline across federal land, Mulroy had gone before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and promised, “An Owens Valley cannot and will not occur in Nevada.”

• • •

In the 1980s, when ground around wells in the Las Vegas Valley had collapsed in feet, not inches, from pumping, geologist Terry Katzer got an idea.

He was in the Nevada office of the Geological Survey, one of the many western research outposts then overseen by John Bredehoeft.

He asked Bredehoeft: Could Great Basin ground water be moved south to Las Vegas?

Not without mining, Bredehoeft responded.

Katzer declined to speak for this series, but Bredehoeft remembers their relationship at the Geological Survey as strained.

As relations soured, Katzer quit and took the idea for pumping the Great Basin to a more receptive audience: the Las Vegas Valley Water District.

In 1985, Katzer became the district’s director of research and in 1986, he hired Kay Brothers, a hydrologist with a bachelor’s degree in engineering from the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology.

Brothers’ background was helping the petroleum industry comply with environmental regulations. As Katzer’s pipeline plan was set in motion in 1999, this was the skill most needed by Mulroy and her newly formed Southern Nevada Water Authority.

Brothers became Mulroy’s director of resources and by 2002, she was named deputy general manager. Second to Mulroy, Brothers became the face of the pipeline project.

Katzer began working for Brothers, his former assistant.

But in the new administrative setup, if the politics lay with Mulroy and Brothers, the science remained with Katzer and his old network of colleagues out of the Nevada office of the U.S. Geological Survey.

If the Great Basin aquifer were to become a major new water supply for Las Vegas, Brothers and Katzer would need someone capable of modeling the effects of pumping.

Katzer turned to his former boss at the Geological Survey’s Nevada office, hydrogeologist Timothy Durbin. Katzer had been Durbin’s principal assistant. Durbin, in turn, reported to Bredehoeft.

Between the time the pipeline idea first horrified Bredehoeft in the 1980s and the moment that his former No. 2 man in Nevada began recruiting his former No. 1 to work on it in 2001, Bredehoeft had left the federal agency and opened a private hydrology practice.

So had Durbin, who had done some consulting jobs for Katzer and Las Vegas.

Durbin was intrigued by the Katzer plan: Here was a chance to come into a massive new project and design it in a way that you could manage the effects.

If, Durbin wondered, that were possible. And it was a mother of an if.

As Durbin joined Katzer and both men looked over the Las Vegas pipeline plan, Durbin saw exactly what Bredehoeft had tried to warn Katzer about those years earlier.

The plan was fraught with risks.

The Great Basin comprises many valleys. Underlying them, the prehistoric jumble of rock and sand is often so permeable that ground water can flow hundreds of miles from valley to valley.

This meant the effects of pumping one valley could conceivably be felt hundreds of miles away.

They would clearly have to avoid pulling water from the sources feeding the four lakes of the Pahranagat Valley, the Muddy River and other places protected by the U.S. Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife and Nevada environmental programs.

The best target for Las Vegas was the lush and lovely Spring Valley, 100 miles long and roughly 12 miles wide. It not only received the bonanza snowmelt of Wheeler Peak, but the aquifer’s flow also seemed relatively contained there.

But they knew there would be sacrifices:

• Depleting spring flows.

• Denuding hundreds of thousands of acres of federally owned grazing and recreational land of its native flora and fauna.

• Supplanting phreatophytes with the nonnative and invasive cheat grass, which by late spring is so dry it is akin to setting tinder at the feet of Nevada’s fire-prone alpine ranges.

• Sullying air around Great Basin National Park.

• Unseating ranchers who were direct descendants of Nevada’s earliest pioneers.

According to Durbin, after years of arguing with Bredehoeft, Katzer too began to see his point.

“There is no free water.”

But to Durbin’s mind, “Las Vegas was not going to go away.”

He knew he could not create public policy. But he could help inform it.

As a scientist, he would lay out the options and the effects, and then the public could decide whether it was willing to make the sacrifices necessary for Las Vegas to tap Great Basin water.

“It’s a societal issue,” he says. “It’s a value judgment. What’s valuable and what’s not?”

The sacrifices implicit in the plan for rural Nevada were so great, particularly for its watery heart of White Pine County, that Durbin half expected Las Vegas to hold them up as proof that Southern Nevada couldn’t possibly tap this source and Las Vegas instead deserved more Colorado River water.

Except by the close of 2003, the pipeline’s inevitable effects weren’t being used to argue for an alternate source of water.

Instead, as Durbin saw it, in pushing the project forward for an ever-thirstier Las Vegas, the Southern Nevada Water Authority began hiding possible outcomes.

According to Durbin, pressure to downplay and even deny the project’s effects started to come in 2003 in meetings with Paul Taggart, the attorney representing Las Vegas’ claims before the state engineer.

The first glimpse of it involved relatively minor hearings concerning a spangle of wells that Las Vegas wanted to sink in Clark and southern Lincoln counties.

According to Durbin, Taggart wanted him and Katzer to testify “no impacts.”

“Neither of us felt we could do that,” Durbin says.

They sent Taggart a memo laying out a strategy, emphasizing the need to kill off phreatophytes for the Las Vegas pipeline plan.

First, Las Vegas could take the pipeline to relatively uninhabited “dry” valleys of Lincoln County.

This would be stopgap. There weren’t enough greasewood-type plants here whose water they could legally intercept.

They would be mining.

But if they used shallow pumps, Durbin calculated, they could spread out effects in space and time in such a way as to be able to stop pumping short of the point that Las Vegas dried up the White and Muddy rivers and the precious lakes of Pahranagat.

This would buy time to get to the more verdant “wet valleys” of the northern cold desert, where mining wouldn’t be such a worry.

There were plenty of phreatophytes in Spring Valley to part from their water.

Once Las Vegas got into Spring Valley, Katzer and Durbin recommended buying water rights from ranchers willing to sell. This would preempt protests.

Then, they recommended, Las Vegas should pump hard to quickly kill off greasewood communities. With Spring Valley on line, they could then ease up in “dry” Lincoln County in time to spare Pahranagat Valley and the White and Muddy rivers.

Their plan — effects and all — on record within the water authority, Durbin and Katzer worked on the model and pumping strategy throughout 2004 and 2005.

But in the background, news that rural ranchers were mounting a rousing defense for Spring Valley’s water played incessantly in the Las Vegas press.

To quell the uproar, Mulroy and Brothers began arguing to reporters and in public meetings in White Pine County that they could pump Spring Valley — and save the greasewood, save the rabbitbrush, save the meadows, even save the alfalfa and cattle ranches.

In other words, they were pledging to save the very things Katzer and Durbin worked so hard figuring out how and where and when to sacrifice.

As the Spring Valley hearing approached in September 2006, after five years’ work, Durbin’s model was finally ready to simulate pumping for the full 90,000 acre-feet of water being sought by Las Vegas. The result? The level of the water table underlying Spring Valley would drop on the order of 200 feet or more over 75 years.

This would, as Durbin and Katzer had envisioned, indeed kill off Spring Valley’s phreatophytes.

It would also end traditional ranching in the valley.

And with no water saturating the top soil and no roots to anchor it, the parched earth of Spring Valley could indeed become a new Owens Valley.

• • •

In 1989, the Department of Interior agencies that manage most of the land in Nevada — the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Bureau of Indian Affairs — had been among the most forceful opponents of the original Las Vegas applications.

As the Spring Valley hearing approached in September 2006, Mulroy and Brothers still faced their opposition.

During a prehearing evidence exchange between Las Vegas’ attorneys and the opponents, the U.S. Park Service received Durbin’s model and ran it.

The Park Service hydrologist came up with the same result as Durbin.

This could have been a brutal embarrassment for Mulroy and Brothers, except on the last working day before the Spring Valley hearing began, all four Interior agencies, including the Park Service, withdrew their protests.

Swallowing hard, the Interior agencies instead agreed to take places on committees to monitor the effects of pumping.

Representatives of almost every agency to sign the agreement explained the logic this way: By settling, they were assured some measure of control and could work with Las Vegas toward its much-vaunted goal of little or no damage. But if they protested and lost, they had nothing.

Durbin, the man trained as a scientific adviser to these very Interior agencies, didn’t think monitoring would work.

“I’m going to guess that even with the monitoring, there will be long-running disputes with one side saying, ‘OK, something happened in the mountains. Was it caused by pumping by the Southern Nevada Water Authority, or did a cow drink all the water, or was it low precipitation?’ ” he says.

The agreement between federal agencies and the water authority meant the Park Service’s running of Durbin’s pumping model (and the result being the same finding of a drop of 200 feet or more in the water table), could not be used in the hearing before the state engineer, either.

So, as the Spring Valley hearing commenced, the man with the most damning case against the Las Vegas pumping plan was Timothy Durbin, the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s own expert witness.

• • •

Almost three years after the meetings that prompted their pumping plan memo of 2003, Katzer and Durbin were back consulting with water authority attorney Paul Taggart over how to mount Las Vegas’ case for the all-important Spring Valley hearing.

Taggart would not comment for this story.

However, according to Durbin, he and Terry Katzer again came under pressure from a water authority engineer and Taggart to soft-pedal the project’s effects.

“At that point, Terry was agreeing with me: That’s nonsense,” Durbin says.

Shortly after preparation for the hearing began with Taggart, Durbin got a call from Katzer.

He had just quit.

Katzer was the one who brought the idea of the Las Vegas pipeline to the water authority in the first place, and then hired Durbin.

But Durbin said he could not follow Katzer’s move in quitting.

In five years as a consultant to the Southern Nevada Water Authority, Durbin had accepted what he reckons was roughly $1 million in consulting fees.

The point of retaining him had been to generate a model for the state engineer. He could not betray his client and walk out just before the first key hearing.

That said, relations between him and his client could not have been worse.

Still, Taggart had little option but to put a now-hostile Durbin on the stand.

In a series of smaller hearings leading up to the Spring Valley one in September 2006, the state engineer had demanded modeling.

As Durbin took the stand before the state engineer on Sept. 14, 2006, he had decided that if anyone asked flat out whether he had run his model and what the results were, he would give the answer.

If not, he wouldn’t.

Durbin was not questioned by Taggart, a man guaranteed to make him bristle, but by another attorney for Las Vegas, Michael Van Zandt.

In more than an hour of detailed testimony, Van Zandt led Durbin on a journey through the minutiae of how models are created.

“Identifying data gaps … version two of that model … just an evolution from version one … simulation of faults … efficient equation solvers … meshes for individual compartments …”

“It was stultifying,” says Matt Kenna, a lawyer from the Western Environmental Law Center representing the protesters. “The incredible irrelevant detail.”

Finally, Van Zandt led Durbin home to the single point Las Vegas wanted to land about modeling: The uncertainty of any result that might embarrass it.

Questioned about margins of error, Durbin responded with yet more mind-numbing detail: “The plus standard error of the estimated water level measurements … are plus or minus 50 feet ... 30 percent chance that the estimated ground water levels are more than 50 feet off what the true level would be …”

When at last the state engineer himself asked Durbin how the model could be used to predict the future of the Spring Valley aquifer if pumping began, Durbin brightened and quickly reeled off some simple steps. Van Zandt — seeing where this was going — quickly interjected to the state engineer, “There will be other witnesses who will probably answer that question for you.”

In cross examination, Kenna had no idea of the hostility between Las Vegas’ attorneys and their star witness, or how accommodating Durbin might have been if asked flat out: “Did he run his model and, if so, what was the result?”

Instead, he fished around the margins and hooked more technical gobbledygook.

Why? According to Kenna, “The standard lawyer’s advice is ‘don’t ask the ultimate question.’ ” The witness might not answer it.

A week later, the protesting parties brought in the lion.

Bredehoeft took the stand for them.

The former Regional Hydrologist Responsible for Water Activities in the Eight Western States was there to defend modeling.

Whether it be to calculate potential effects of nuclear waste leaking from Yucca Mountain or predict effects of Las Vegas’ pumping of Great Basin ground water, Bredehoeft insisted that modeling was the only tool available to help inform public policy decisions. “That’s it. We don’t have another tool.”

This time Taggart was representing Las Vegas.

Bredehoeft was well aware that Durbin hadn’t given the result of his model, so he let drop that the Park Service had also run it and produced a written a report on the result.

“Objection!” Taggart called. “Those documents are not in evidence and any statements about what the predictions in those models say would be inappropriate.”

The upshot: The Park Service report was also suppressed.

And so predictions by the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s own modeler and the former head of the Nevada office of the U.S. Geological Survey about what the cost to the Great Basin might be from Las Vegas pumping were never entered into evidence.

“I allowed myself to be badly used,” Durbin says. “I’m an adult. I allowed it to happen.”

• • •

It’s April 16, 2007, 3:30 p.m., at the Las Vegas offices of the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

Pat Mulroy halted a conversation in midsentence to reach for a pulsing BlackBerry. As she read the text message, a small smile crossed her face.

Tracy Taylor, Nevada’s state engineer, had just granted the authority somewhat less than half the water it asked for — 40,000 acre-feet a year for 10 years.

In return, the authority would be required to “file an annual report by March 15 of each year detailing the findings of the approved monitoring and mitigation plan.”

After this, and presuming success, the amount could be raised to 60,000 acre-feet a year.

“Now, bear in mind, we’ll be in Lincoln County first,” a briefly triumphant Mulroy explained. “And in the Lincoln County basins, there’s no one. No one!”

She was referring to Cave, Dry Lake and Delamar valleys, three of the four basins that Katzer and Durbin envisioned tiding Las Vegas over until Spring Valley could be aggressively tapped.

By December 2007, the state engineer’s hearing concerning Dry Lake, Cave and Delamar valleys was approaching. Las Vegas was seeking a total of almost 35,000 acre-feet a year.

Attorneys for Mulroy and the protesters were in the by now familiar pretrial ritual of exchanging evidence lists.

Among the scheduled witnesses was Timothy Durbin, except this time he was not testifying for Taggart, Brothers, Mulroy and the water authority, but for the legal team representing the protesters.

Shortly after Christmas, Durbin’s phone began to ring.

The first call had two people on the line: Taggart and an engineer from the water authority. Durbin says they wanted to know whether it was true he was testifying and what he would testify about. “I was pretty guarded there. I don’t trust those people at all.”

The second call, Durbin says, came from Katzer.

“I told him I was feeling uncomfortable with my testimony in the Spring Valley hearing and I thought that the Southern Nevada Water Authority had an obligation to disclose what the impacts were going to be and that was hidden in that hearing.”

The third call came from Mulroy’s deputy. “I told Kay the same thing. Basically Kay said she was she was disappointed but she respected my right to do it.”

On the morning of Feb. 11, 2008, a clearly nervous Durbin again took the stand before the state engineer of Nevada.

“Please come forward and be sworn, Mr. Durbin. Nice to see you again,” a curious hearing officer said.

And so, with Taggart objecting a few times, Durbin more or less recited to the court distillations of the memos that he had sent during the past four years to Taggart and Mulroy about sacrificial choices and the problems of monitoring.

“All that the monitoring and mitigation can do is shift the focus of the impacts ... I believe that their (Southern Nevada Water Authority’s) reliance on monitoring and mitigation is most likely not going to work,” he said.

Las Vegas owed it to the public to discuss what the environmental effects of its Great Basin water were going to really be, he said. “I think that for everybody concerned, including the rate payers in Las Vegas, that it’s better to have that discourse now.”

Protesters braced themselves for a Las Vegas retort to Durbin’s appearance.

There was none.

The strategy all along had been to keep Durbin’s concerns off the record. Now that he’d had his day in court, they were not about to call attention to it.

• • •

Nearly four years after pledging to the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources that modern protections make a repeat of Owens Valley impossible, Mulroy maintains the position.

Of Durbin’s work, she says, “It’s just a model!”

Shortly before publication of this series, Mulroy’s information officer dismissed the Durbin-Katzer memo as “recommendations from two consultants to a contract attorney on one potential course of action. That is two bus transfers and a cab ride short of being a policy.”

Brothers has heard the Owens Valley comparison so often for so long that the mere mention of it in an interview for this story made her irate.

“They’re totally different projects,” she snapped. Owens Valley had a large lake. “To even compare them is to be out of date and not understand what a ground water project is versus surface water.”

Also, she noted, William Mulholland and early Los Angeles were not subjected to the modern protections ensured by federal government.

Part of Brothers’ management strategy for Spring Valley involves still-evolving ideas about capturing water that streams off the hills in springtime, then evaporates on hot playas.

Ideally, she’d like to force this into the ground, just as she and Katzer used injection wells to store unused river water in the Las Vegas Valley.

They also might use water purchased from the ranchers to help maintain the phreatophytes.

“I’m not saying that you would never lose a greasewood,” she said, “but I think you would never lose much at all by managing it properly.”

Brothers is confident that if she sat down with Bredehoeft, Durbin and Katzer, they would see her point.

Becoming soothing, she added, “I don’t know that we disagree.”

But on hearing this, the normally shy Durbin retorted, “I hope she’s lying, because otherwise she’s a bad scientist.”

In the early 1980s as then-director of the Geological Survey’s California office, Durbin led modeling teams looking precisely at the effect of Los Angeles’ pumping on Owens Valley phreatophytes.

Removing water from the playas, Durbin said, almost perfectly emulates what Los Angeles did, first draining Owens Lake and then pumping the ground water.

“The Owens Valley is a model of what to expect,” he said.

Moreover, he added, playa water plays a key role in keeping down alkaline dust.

Another key part of Brothers’ strategy is moving pumping around so as to “rest” certain areas.

But to Durbin, this wouldn’t decrease the effect, but make it more diffuse, difficult to track and hard if not impossible to reverse once damage became evident.

“We know from basic physics that in some time or some place the impacts of the pumping will be equal to the volume of the pumping,” Durbin said. “You don’t need a ground water model to make that statement with absolute certainty. It’s simple. If you take water from one place and give it to another, it will be missed at the other end.”

With the pipeline originator and his chosen modeler, Durbin, now gone, among the rank of scientists now reporting to Brothers is a new modeler from the U.S. Geological Survey.

His model, still under construction, will not be able to embarrass them.

It will be used only to contrast predictions against measured effects of actual pumping.

If monitoring wells and models both suggest there are problems, monitoring committees will seek “consensus-based” actions.

Mulroy’s and Brothers’ new team speculates greasewood may do just fine on rainwater that percolates around root zones.

Mulroy and Brothers say they now have extra water to irrigate Spring Valley’s greasewood if necessary and to keep the ranches working, except with more efficient irrigation.

The Southern Nevada Water Authority plans to pump the Great Basin indefinitely.

It will revisit how much it intends to pump, possibly returning some water to White Pine County, only after paying off the pipeline in 75 years.

Unlike the original Katzer-Durbin plan, they do not see the water now being sought from the “dry” valleys of Cave, Dry and Delamar as temporary.

“I don’t think in the lifetime of this project, we’ll affect Pahranagat Springs,” Southern Nevada Water Authority hydrologist Andrew Burns says. “But having said that, we’ll have monitoring of those pumping wells and those areas. If we see effects, we’ll have opportunity to move the pumping around.”

The long and the short of it, Burns concludes, is “we’re going to pump what’s permitted to us.”

• • •

If this were fiction, the story would have a neat ending. But this being about the search for water in Nevada, it doesn’t.

• The Southern Nevada Water Authority hopes to start importing Great Basin ground water in 2015.

• The state engineer’s decision for Cave, Dry Lake and Delamar valleys is expected by October.

• Pretrial hearings over Snake Valley begin in mid-July and a hearing is expected by the end of the year. Because Snake Valley sits on the state line, water will not be able to be taken from the valley until Utah approves it.

• The latest estimate of the pipeline cost is $3.5 billion, eliciting the quip from Ely Daily Times Editor Kent Harper that it would be cheaper for Las Vegans to bathe in Dom Perignon than Great Basin ground water.

• If the Great Basin pipeline project fails, and drought persists on the Colorado River, Las Vegas’ decision to keep building and dare the Department of Interior to let it run dry will probably pay off. Few think that Uncle Sam would cut off a city.

But Las Vegas would have to learn to live within its means — maybe by slowing growth — while searching for alternate sources: building a desalination plant in California or Mexico then exchanging it for more Colorado River water and pursuing more aggressive indoor conservation.

• Whatever the outcome of Mulroy’s pipeline, Nevada Senator Harry Reid says, “you have to recognize what Pat Mulroy’s done with conservation. If she has no other legacy other than what she’s done to conserve water in Southern Nevada, her legacy is very significant.”

• Former Clark County Manager Richard Bunker, the man who groomed Mulroy to become Las Vegas’ water manager, is largely retired.

One of the last jobs this fifth generation Southern Nevadan vows to do for Las Vegas is to represent Mulroy in negotiations for Snake Valley’s water.

When Bunker is finished with the Utah negotiations, he plans to spend as little time in Las Vegas as possible. He devotes most of his time now to his ranch — in Utah.

Las Vegas no longer feels like home, he says.

“It’s too crowded.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy