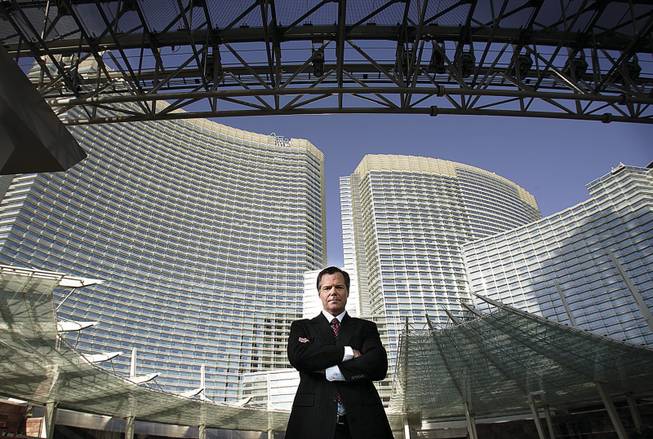

Jim Murren, the CEO of MGM Mirage and a transplanted New Yorker, stands in front of the Aria at CityCenter, a project he conceived based on what he thought Las Vegas lacked: a world-class urban gathering place for the city’s residents. “We were missing so many important quality of life building blocks — what I would consider to be not extras but essentials, culturally and medically. The diversity that I grew up with in New York isn’t here.”

Sunday, Nov. 29, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Jim Murren: CEO, MGM Mirage

Jim Murren, CEO of MGM Mirage, reflects on the beginning of CityCenter and what it will bring to Las Vegas.

Sun Coverage

Visitors to CityCenter, the Strip’s newest spectacle, will be driven to look up at the glistening glass and steel. It is an inexorable pull, to cock your head backward and take in the sweep of six high-rise towers — including two that lean — that create an urban scene unlike any other.

The man who conceived of this place, however, would like to draw your attention to a small park bench.

It is found near the center of the 67-acre site, alongside Aria, the flagship high-rise filled with 4,004 guest rooms above a sprawling casino, convention center, the Strip’s newest showroom and, to greet visitors, a boisterous demonstration of water cannons.

Tucked between the 61-story Aria and the fanciful, futuristic retail promenade known as Crystals, Murren will show you the park bench, under the shade of a Zen-like cluster of trees. This little pocket park, he says, may be the most precious real estate in all of City Center.

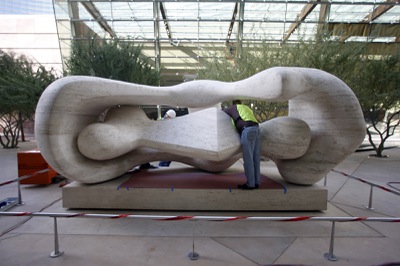

Sitting here, you can contemplate Henry Moore’s “Mother and Child,” a massive marble sculpture, or gaze through the glass and into the lobby of Aria and, hanging above the front desk, see Maya Lin’s “Silver River,” a 3,700-pound, 87-foot rendition of the Colorado River’s winding, graceful journey through the Southwest.

“If you sit here and look at the sculpture and up at the Aria tower and see how it shimmers in the sunlight, you will think you’ve been transported to a different place,” Murren says. “It’s like nothing I have seen before.”

To grasp the importance of this pocket park — and to understand why MGM Mirage decided to risk the company’s future by building one the world’s most expensive resort complexes — one must understand Jim Murren, the company’s chief executive.

CEO’S background

Before he took the helm of MGM Mirage, and before he was a financial analyst on Wall Street, Murren, 48, was an artist who dreamed of becoming an architect.

As a child growing up in Fairfield, Conn., Murren took frequent trips with his mother to New York City. There, the wonders of suburban life were overtaken by the drama of the big city as he walked through Manhattan’s many colorful neighborhoods and museums.

Inspired by his mother, who painted watercolors as a hobby, Murren took classes in oil painting. His rural landscapes and seascapes were good enough to earn him shows at his high school, the local library and other public spaces.

Murren nurtured his interest in art at Trinity College, a small, private liberal arts college in Hartford, taking his first art history course freshman year and spending a semester of his junior year in Rome studying Renaissance and Baroque art. Trinity operates a campus in a converted convent on Aventine Hill, a cultural landmark that overlooks the ancient city. In this impossibly romantic setting, Murren developed a fluency in Italian, “fell deeply in love with the aesthetic of art” and poured himself into painting city scenes.

This seemingly right-brained existence was counterbalanced by an equal interest in left-brained activities. Murren excelled at math, enjoying the analysis involved in picking apart and solving equations that would make many creative people run in the opposite direction.

In addition to art history, Murren accumulated several classes in urban studies — a field that often leads to work in government planning and architecture. During college, he interned with a nonprofit housing developer in Hartford.

Murren decided to become an architect — a career that seemed to balance intuitive and creative thinking with numbers-based analysis.

And then, during a post-college tour of Europe, Murren quickly ran out of money, sleeping in train stations and on beaches. Shaken by his brief, penniless existence, Murren ditched architecture, which would have required more education without any guarantee of a good-sized paycheck at the end of it all.

Like many people with a knack for numbers, Murren joined the ranks of the dark-suited men on Wall Street he had admired as a boy walking through Manhattan.

“I wanted to make money — lots of money,” he said.

Wall Street appealed to his competitive side — the side that played football and baseball in school. Art took a back seat.

In 1984, Murren jumped at the chance to earn $18,000 a year — good money for an art history and urban studies major learning the investment banking business — as a research assistant for a stock analyst.

During off hours, Murren studied to become a Chartered Financial Analyst, a professional designation given to people who pass three sets of examinations. He became expert at analyzing companies’ balance sheets, rating their stocks and evaluating their overall financial health.

He rose steadily up the corporate ladder, eventually reaching the top of his profession at Deutsche Bank, an investment bank that had developed a specialty in the casino industry. In Murren, who was covering MGM Mirage’s predecessor company and other gaming giants, then-CEO Terry Lanni spotted a young man who wasn’t afraid of asking pointed questions of management and who quickly grasped the potential of high-end resorts in Las Vegas.

Rise at MGM Mirage

Lanni hired Murren as chief financial officer in 1998, the year Bellagio opened, triggering the Strip’s largest and most ambitious growth spurt, which included Mandalay Bay, Venetian, Wynn Las Vegas, Palazzo and Encore.

In Las Vegas, Murren found a community with a good standard of living, great weather and a business-friendly culture rich with entrepreneurs. He would no longer be one analyst among many but a top executive with a major company still in its early growth stage. Still, it was a difficult adjustment for the New Yorker and lover of high culture.

Murren’s wife, Heather, also a high-powered Wall Street analyst, had never even been to Las Vegas.

“She’s very much of a risk-taker. I was more reticent in coming. I had a good gig ... we had a nice house in Connecticut, a nice apartment in New York and solid careers.”

Early into his move, Murren acknowledged a “gnawing sadness” about the relative lack of culture and community icons in Las Vegas.

“We were missing so many important quality of life building blocks — what I would consider to be not extras but essentials, culturally and medically. The diversity that I grew up with in New York isn’t here.”

One of those things, Murren thought, was a world-class urban gathering place. Downtown didn’t fit the bill, nor did anything on the Strip, which was a place where local residents typically went only with out-of-town guests or on special occasions.

“There was no impetus or inspiration to jump in the car and go see, what, another hotel? Another casino was not going to do it for people,” he said.

His artistic sensibilities were rekindled during his travels abroad. Unlike his New York-centric life on Wall Street, Murren’s new job as CFO took him to major cities, including possible sites for casinos and resort hotels such as Tokyo, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and Beijing. New York was largely a city of older buildings, but many foreign cities were experiencing a wave of construction highlighted by striking modern architecture. As CFO, Murren’s job wasn’t to come up with ideas for new resorts, but rather to manage the company’s money. But his right brain, long dormant, chafed.

“I started getting very frustrated with sitting through meetings to talk about yet another hotel idea. It was more of the same, with a different theme, different position, different partner. Everything we were looking at before I thought was just a worthless enterprise.”

Murren found an early sounding board in Kirk Kerkorian, MGM Mirage’s majority shareholder and a man who thought big. Kerkorian built the world’s largest hotel twice, with the International hotel, now called the Las Vegas Hilton, in 1971 and MGM Grand in 1993. In Murren, Kerkorian found a man who wasn’t just another number cruncher who followed direction from others but an executive with ideas of his own.

“He kept challenging me, without saying what it is I should think of, to think beyond what I could see,” Murren said. “I admired him so much that I thought a lot about ... what I could contribute to the company.”

That was before 9/11, which devastated tourism in Las Vegas and left people such as the Murrens, with their ties to New York, emotionally stricken.

Rather than burying himself in the financial section of The New York Times, Murren felt drawn to the architecture page and the process of developing a memorial at ground zero.

When the economy healed, MGM Mirage had ascended to a powerful position after the company’s 2000 acquisition of Steve Wynn’s Mirage Resorts — a deal triggered by Kerkorian and designed by Murren.

By 2003, with the company in good financial shape and its casinos generating record earnings, Murren began to draw.

Mortgaging land

What he drew was based on a new way of thinking about the casino and resort industries on Wall Street. Bankers had crafted a new investment called commercial mortgage-backed securities as a financing tool for companies with lots of usable land. Instead of issuing stocks and bonds to fuel growth, companies could issue mortgages against land they owned, package the loans and sell them to investors.

Such loans became the jet fuel that launched a wave of casino acquisitions by private equity firms that saw a seemingly low-risk, reasonably priced way to finance such deals.

Like banks before them, private equity companies — firms that snapped up companies during the recession by borrowing heavily on the cheap — had shunned casinos as high-risk investments subject to heavy regulation.

Eventually, casinos became Wall Street darlings for their high profits, large and steady revenue streams — all the better for paying down massive debts quickly — and potential for growth.

Real estate, especially along the three-mile concentration of resorts on Las Vegas Boulevard, skyrocketed in value as investor interest grew. Murren’s slow-burning idea that the company should build an urban, high-density resort destination happened to coincide with the exponential growth in real estate values. Land that had once been worth hundreds of thousands of dollars as, say, surface parking for casino workers was now worth tens of millions per acre as an investment tool that could enable a company to build a profitable luxury resort on that parking lot.

Readying the pitch

By early 2004, Murren had combed through art and architecture books to flesh out some simple architectural drawings, which included towers not just for hotel rooms but for condominium units and office space. In the meantime, he would engineer his next major deal — acquiring Mandalay Resort Group, a competitor with several large hotels, including Mandalay Bay, Luxor and Excalibur. The combined company would dominate the Strip with 10 major resorts and, more important for the company’s future, give MGM Mirage control over dozens more acres of undeveloped land that was now more valuable.

Unknown to Mandalay Resort Group at the time of the deal was a second, equally important reason to buy the company. Mandalay owned land behind the Monte Carlo, which it owned with MGM Mirage. Acquiring Mandalay would give MGM full control of the Monte Carlo and the acreage behind it, which would enable MGM Mirage to build CityCenter at the large scale Murren envisioned.

In early 2004, about the time Murren was negotiating to buy Mandalay, he took a grease board drawing of his plan for the site of what was then the Boardwalk casino. Using a computer program of the kind used by architects, he created more detailed plans with some help from Bill Smith, an architect and president of MGM Mirage Design Group, the company’s resort development subsidiary. During a lunch break in a company board meeting to discuss other issues, Murren stood the drawing on an easel and began discussing his idea with board members.

“I told them how Las Vegas was designed, every resort, to fight one another, not only thematically but from an egress perspective. How yesterday’s thinking told you, ‘Let’s put a moving sidewalk only into a building and ... force you to go through a casino.’ And how, if we created something with expert urban planners and put world-class architects into the mix, we’re going to stretch the boundaries of our knowledge and create something that would be a gift, a resource to the community that we could make a lot of money on.”

The board members — except for Kerkorian, who was sold on the idea early on — were intrigued but skeptical of the plan, which called for building many towers at once and creating a campuslike environment where pedestrians could amble from one building to another.

“The financial (executive) would have said that’s a gigantic waste of money, that we should carve this up into smaller pieces and build very cost-effective buildings, including a Y-shaped tower up next to the street,” Murren said. Some casino operators also blanched at the plan, which called for a casino located far back from the sidewalk and set apart from most of CityCenter’s other features.

But Murren never doubted the success of CityCenter. It was right for the company, right for Las Vegas. “I know this like I know I’m left handed,” he would say.

In March 2004, Murren convinced the board that the stars had aligned for MGM Mirage to up the ante for what could be accomplished on Las Vegas Boulevard — a place that, after all, had inspired such outlandish yet immensely profitable creations as a reconstructed Venice and a South Pacific-themed resort in the middle of the desert. No place but Las Vegas, with its nearby airport, tourist volume, widespread popularity and a tax and regulatory climate that encouraged growth, could support such an attention-grabbing project, he said.

This plan was inspired not by Murren the CFO but by Murren the dormant urban planner.

Making it real

While Murren was raising billions of dollars on Wall Street to acquire Mandalay, he was assembling a team of executives to oversee CityCenter, including Bobby Baldwin, who had opened several resorts for Steve Wynn, including the Mirage and Bellagio.

This team began hiring firms to compete in a design challenge for CityCenter. MGM Mirage decided on EE&K Architects, a company with offices a few blocks from the Union Square apartment in Manhattan where Murren had once lived and the firm that had created the master plan for New York’s Battery Park City.

EE&K built on Murren’s ideas, moving the casino-hotel back from the street and creating a wide boulevard up to the building and a rerouted Harmon Avenue with a traffic circle and large, second entrance behind the property. Retail stores would front Las Vegas Boulevard in a low-slung building with multiple entrances that would be less imposing for passers-by. Buildings would be different shapes and sizes, each an attraction unto itself and, taken together, a modern landscape of epic proportions.

With Murren’s input, Baldwin and other key executives narrowed a list of about 100 architects to a few dozen, including a few marquee names. Those chosen to work on CityCenter would be world-class creators of iconic structures known to draw crowds of spectators. They would be known for their public spaces such as museums and theaters but capable of building profitable structures for entertainment purposes. They would be chosen for their ability to collaborate on a scale that had never been attempted in the field of architecture, where buildings were typically designed as stand-alone structures.

Some have called CityCenter a themed version of New York as envisioned by a Manhattan transplant — different in design but not in concept from the faux Venice of the Venetian or a modern take on the faux skyline of New York-New York.

Yet Murren’s primary inspiration for CityCenter is a great distance from New York, in places such as Kuala Lumpur and Abu Dhabi that have created modern skylines from scratch with the help of big-budget architecture firms. CityCenter, Murren says, incorporates many styles of architecture, though lay persons may view them all the same way — as simply modern, with angled lines and sleek curves.

And indeed, when Murren rhapsodizes about CityCenter, he doesn’t always sound like the tough CEO he is.

He talks of how pedestrians will walk in and between the buildings and contemplate large paintings and sculptures by master artists, many of them commissioned for CityCenter. People who have never pulled a slot machine handle or played a hand of blackjack will walk through CityCenter and, just maybe, they will be inspired to create art, design buildings or simply do something different with their lives, he said.

This is his right brain speaking, not the kind of marketing spiel one would expect from a sharply-dressed CEO. Is this merely a different approach to marketing? Does the secret to mining deeper profits in Las Vegas lie in the contemplation of great art?

It’s a bit of both for Murren, who can just as easily recall the awe he felt as a child seeing his first dinosaur at New York’s Natural History Museum as he can recall marathon sessions with investment bankers in February to negotiate his company — heavily leveraged with debt and pummeled by the recession — back from the brink of bankruptcy.

“This is the best possible sandbox to play in,” he said. “There is no place in the world where we could have done this.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy