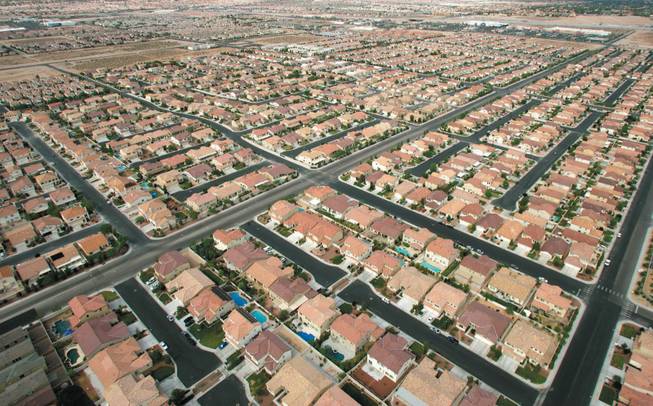

Sam Morris / Las Vegas Sun file

Houses sprawl across the Las Vegas Valley. When the housing bubble burst in 2007, Las Vegas became the No. 1 area in foreclosures nationwide.

Friday, Jan. 1, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Related Story

Sun Coverage

Sun Archives

- 2010 – The Decade Ahead (12-28-2009)

- Nevada's Top 10 political stories of the decade (12-20-2009)

As Las Vegas limps into a new decade, let us return to the now-hazy origins of our current sickness: 2005.

It would seem the entire Las Vegas Valley had been slipped a drink laced with a financial hallucinogen — a powerful narcotic that combined Ecstasy’s feelings of well-being with methamphetamine’s urge to be busy.

Even the city’s most accomplished business and political elites could not resist its influence. They were spaced out, convinced that the laws of the economic universe had been suspended, that housing prices could expand into space, that borrowing money was as holy as prayer.

“We thought we had a recession-proof economy, we thought we would grow forever,” says Elliott Parker, a UNR economist.

Parker describes an “illusion, that we could create wealth from nothing, that we could keep consuming beyond our income, that housing prices would keep rising, that investments could yield high returns without risk, since we were all so clever ...”

If they weren’t addicted to the drug themselves, Las Vegas denizens acted as street corner touts — marketing the magical drug for a living — and were always shouting its wonders.

We were, in Parker’s words, “selling high roller fantasies to gamblers and expensive houses to people who sold their homes elsewhere for even more insane amounts of money. We thought it would continue forever, and we made no contingency plans for the alternative.”

Illusion. Fantasy.

When skeptics pointed out that perhaps a dangerous real estate bubble was forming, the crowd responded with mockery:

“The only bubble you’ll see in this market is in a Champagne glass,” a well-known real estate player said in our now fated year of 2005.

But in fact, here’s what was happening in the Las Vegas real estate market: After years of slow and steady growth, a mania took hold. Home values had increased more than 35 percent in 2004 alone.

It was a classic bubble by 2005, right up there with phony Silicon Valley technology companies 10 years ago, and phony Amsterdam tulip futures 375 years ago.

For a while, Americans could borrow unlimited sums of money against their rising home values to come to Las Vegas to spend money. So we built new resorts.

We needed construction workers to build those resorts. We needed other construction workers to build homes for the first construction workers.

Simple logic

This wouldn’t — couldn’t — go on forever. At some point, Americans would hit their limits and the growth of tourism would slow, and we wouldn’t need so many construction workers to build resorts, and then we wouldn’t need so many construction workers to build those houses for the first construction workers.

Once we didn’t need those construction workers, they would be laid off and stop making mortgage payments on their homes. And the sell-off would begin. Throw in all the subprime loans that borrowers couldn’t pay to begin with and you’d get a fire sale. Welcome to 2007.

It’s simple logic, really. Any college freshman who got suckered into a pyramid scheme could explain the illogical underpinnings of it all. It was an economic house built without a foundation on a sandy desert hillside. And there it goes, into the wash.

Sure, we had the resorts, and the wealth they created was real, but the Strip was living on borrowed time, larded with debt, a bad recession away from near collapse and in some cases, bankruptcy.

“A growth-addicted economy produced phony prosperity,” says Hugh Jackson, proprietor of the Las Vegas Gleaner blog and a policy consultant to the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada, a liberal advocacy group.

Phony. Like the happiness of a drug.

This isn’t to say that the decade didn’t begin with hopeful signals — low unemployment and rising wages, and the tax revenue needed to improve schools, health care and social services. The Strip kept attracting more customers and building more hotel rooms to house them.

But the 9/11 terrorist attacks should have provided a clear warning that a dip in tourism could pummel the city. When tourism quickly resumed, however, that warning went unheeded.

Plus, debt was accumulating, in households here and among potential customers around the world, and on corporate balance sheets.

It should have been a portentous time, a ripe time for Cassandras.

“The decade began with a facade,” Jackson says of those go-go years.

A facade. Soon it was a Potemkin village of steel and stucco, massage parlors and pawn shops.

So wrong

In the reality-based world, many people knew the intensifying speculative bubble in real estate wasn’t sustainable and tried to warn others. Bill Robinson, a UNLV economist, sold his house in 2005, patiently explaining to neighbors the laws of economic reality and the coming crash.

“Everybody who was independent of all this saw it coming,” Robinson says. Meaning everybody sophisticated enough to understand economic data and not a paid representative of the resort or development industries.

(And, in fairness, some people from those industries tried to pull the fire alarm early on.)

What is striking about our real estate player, the one who sneered about there being no bubbles except those in Champagne, isn’t that he turned out to be so wrong. After all, people are wrong all the time. The sun revolved around the Earth for centuries after Ptolemy, and many smart and well-meaning people, even the high priest of laissez faire capitalism Alan Greenspan, were wrong about the housing bubble.

No, what’s striking is the tone of triumph and arrogance, like he’s pulled one over on the stupid herd.

It turns out, our addiction’s true power was so much like that of other drugs: It gave the user great powers to deceive.

We were good at deceiving others.

“Hardly anything we did this decade was upfront,” Robinson says.

Illusion has always been part of Las Vegas’ appeal — that we would not succumb to mathematical certainty at a card table; that we could come here and remake ourselves into glamour gods; that buildings that look like the New York City skyline can approximate the feeling one would get from actually being in New York City.

Illusion is one thing.

Deception, done with malice and for the most selfish ends, is something else.

Deception in Las Vegas took many different forms this decade.

Easy to con

On the Clark County Commission, four members would eventually be convicted of what amounted to dishonest service for taking bribes. Erin Kenny told us she was acting on the community’s behalf when she pushed approval of a CVS drugstore at Desert Inn Road and Buffalo Drive. Really, it was for a $200,000 bribe.

From the sensational to the prosaic: The real estate loan officers who extended money to people knowing they couldn’t repay, demanding no documentation, employing no safeguards or due diligence.

So, waddya make last year?

Oh, that’s good enough.

“Stated income,” we called these loans, employing our bottomless ability for euphemism.

Or, our lenders weren’t straight with borrowers — many who didn’t speak English — about what would happen to their monthly payment in a year or two after a “reset.”

On the other side of the ledger, there were speculators and plenty of average people who took out loans they had no intention of repaying.

“The easiest con for a con artist is another con artist,” says Mike Green, the Nevada historian. “If you want to believe you’ll always be living on the Big Rock Candy Mountain, then it’s easy for someone to sell you another piece of worthless land.”

Once things started to collapse, a whole new set of scam artists — “loan modification specialists” — preyed on vulnerable homeowners, promising to keep them in their homes but running off with cash instead.

For so many — and at great expense to the rest of us — the decade was a giant con, a bamboozlement, a flimflam.

“We have a history of benefiting from all that flimflamming,” Robinson notes.

“It’s kind of our culture. So at some point it was inevitable that if there was an easy-money climate, we would fall prey to it,” he says.

Which brings us back to another kind of deception, perhaps most damaging of all — self-deception.

“It’s easy to delude yourself into believing something you want to be true. And here we are,” says Mike Sloan, a gaming consultant and former state senator.

We were deceived, we were narcotized, because we wanted to be deceived.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy