Friday, Jan. 1, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Related Story

Sun Coverage

Sun Archives

- 2010 – The Decade Ahead (12-28-2009)

- Nevada's Top 10 political stories of the decade (12-20-2009)

For Las Vegas, the end of the 2000s has been the equivalent of the housekeeper walking into a Strip hotel suite midmorning, cranking some Christian rock, and then Tasing the bedridden guest who is nursing a bad hangover.

A painful awakening.

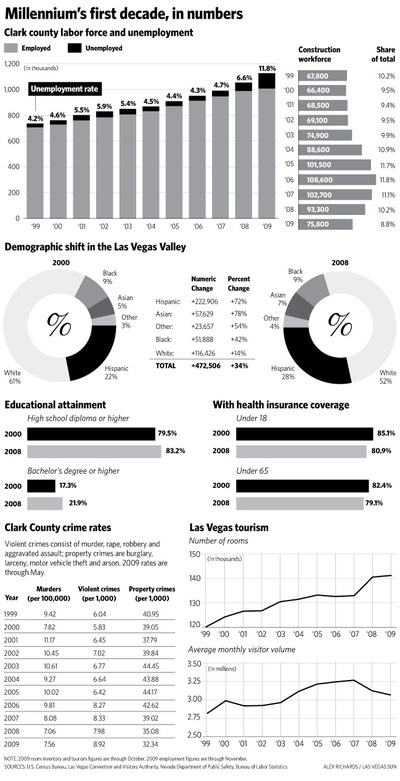

The decade began like any boozy party, with backslapping and uproarious laughter following lots of new jobs, climbing wages and rapid building all over the Las Vegas Valley. But it has ended with heartache and headache: historic unemployment, property values sunk back to 2000 levels and skyrocketing bankruptcies.

The Sun asked a few local elites what lessons should be learned.

Insanity: Doing the same thing over again and expecting a different result

This may seem circular, but what is the first lesson to learn? Learn your lesson, and move on.

“Lesson One is we can’t go forward the way we lived in the past, which was catch-as-catch-can and everything will work out,” says Billy Vassiliadis, CEO of R&R Partners, the advertising and public affairs firm.

Jim Russell, a geographer and Colorado redevelopment consultant who writes about the struggles of Rust Belt cities on his blog Burgh Diaspora, says the lesson Las Vegas can learn from faded industrial cities is: “There isn’t any quick fix. There isn’t any way to recapture the glory. The sooner you put the past behind you, the better.”

Vassiliadis adds: “The economic fantasy of the past 20 years is over. Smart, gutsy, dedicated people need to get together and make decisions.”

What he means is that there was a way of doing things in Nevada for a long time: Lean on gaming and growth and development; spend what’s available to prop up ailing schools, hospitals and social services; tell people to mostly fend for themselves; let the chips fall where they may.

So if that’s not the plan anymore, now what?

Payday loan centers and tattoo parlors don’t count as economic diversity

“We have to stop talking about diversifying our economy and actually accomplish it,” Assembly Speaker Barbara Buckley says. “There’s been lots of discussion but never has the point been made clearer these past few years that gaming is not recession-proof.”

Here’s an economy that never diversified, despite endless warnings: Detroit.

Mark Muro of the Brookings Institution echoes the late UNLV economist Keith Schwer when he says we’re too dependent on consumption. More than half of our metro gross domestic product comes from consumption — gambling, strip clubs, food and beverage, hotel rooms. The only other metro area in the country that comes close is Orlando, Fla.

“The consumption formula, based on historically low savings rates, is a dangerous source of economic energy going forward,” Muro says.

We need to leverage our expertise and resources in travel, tourism and convening, while also expanding our presence in clean energy, so that we’re exporting both energy and expertise and less reliant on plain old consumption, Muro says.

So, how do we do this?

Education, education

It’s no mystery. As Republican state Sen. Randolph Townsend says, “Without an intensely educated workforce in the areas we can be best in, we will never be the state we’re capable of being.”

This doesn’t mean trying to turn UNLV into Harvard, or even Berkeley, he says. Just focusing on our potential — like we already have with hotel management — and could do with health care and water and energy research.

Better schools will have another salutary effect, says former state Sen. Warren Hardy, now a Republican lobbyist. Improved schools will bring companies that need an educated workforce, leading to still more educated people moving here. “Taxes are low on the list of what good companies look for when they decide to relocate. They want quality education, health care, culture. And we’re behind the curve,” he says.

The debate about how to improve schools is complicated, but one thing is clear, according to Republicans such as Hardy and Townsend, and Democrats such as Vassiliadis and Buckley: We need a more stable tax structure that provides more revenue, and improved accountability measures.

Spin the wheel and around she goes — hope for the best, kids

The state’s tax structure depends heavily on gaming and tourism as well as the now-dormant growth and development industries.

“We built tax policy around the boom. That’s not very smart,” Hardy says.

Townsend concurs: “It’s obvious to everyone no matter where you are on the political spectrum that the tax structure we currently have is no longer a functioning mechanism to fund the tremendous demands of schools, social services and corrections.”

Unfortunately, Nevada is in a bit of a vicious circle. We can’t diversify the economy without better schools. We can’t improve the schools without some new money from a diversified tax base. But there won’t be new money until we diversify the economy.

The end and the beginning of libertarianism

Libertarianism was an important catalyst of Nevada’s development. Quickie divorces and gambling helped Nevada through the Depression, and low taxes and a light regulatory touch have attracted businesses and residents ever since.

Over time, that libertarianism has become more like a child’s security blanket — part of our identity, addictive, but in the face of some pretty big market and regulatory failures during the past three years, useless.

“If you have reasonable regulations in key industries, it prevents chaos,” Buckley says. She cites a legislative audit that found lax regulation of the mortgage lending industry, which could have contributed to the housing meltdown.

Others have suggested, however, that a new libertarianism could help Nevada through its current troubles. California and Colorado, for instance, are quickly becoming known for their de facto decriminalization of marijuana possession. Doing so here could attract pot-loving tourists.

Quality over quantity

“Over time we’ve pursued a policy of ‘Let’s chase growth at all costs.’ All growth was good, and in retrospect, we should have been more selective about how we grew and who we attracted here,” says Thom Reilly, former Clark County manager and now a vice president at Harrah’s.

For Reilly, this means attracting companies that pay good wages and benefits and are solid corporate citizens.

He says we attracted low-skill, low-wage American and foreign-born workers, many of them disconnected from network of family and social support. So, once the recession hit, they leaned hard on nonprofit groups and government, which were threadbare to begin with.

This glut of unskilled workers also made us more vulnerable to the recession. The unemployment rate is 10 percentage points lower for Americans with college degrees. Las Vegas has one of the lowest percentages of college-educated citizenries in the country.

“You want a balance,” Reilly says.

Russell, the geographer and Burgh Diaspora blogger, says rapid growth masks hidden problems.

“An influx of migrants makes policymakers lazy. If you screw up, the growing numbers of people will hide your mistake,” he says.

The kids like the trains

Reilly says not developing light rail during the past decade, unlike, say, Phoenix and Seattle, will have long-term negative consequences. That failure prohibits us from developing a more diverse settlement pattern of transit-oriented retail and residential development.

The educated segments of Generations X and Y grew up in the suburbs, and many of them now hate the ’burbs and want to live in urban environments, at least until they have kids. (Which is later in life than any generation in history.)

The evidence? Urban property values are rising relative to suburban property values.

As University of Michigan urban planning scholar Christopher Leinberger noted in The Atlantic last year: “Urban residential neighborhood space goes for 40 percent to 200 percent more than traditional suburban space in areas as diverse as New York City; Portland, Ore.; Seattle; and Washington, D.C.”

Without light rail or some kind of viable transit, we’re an auto city. Which really means we’re a giant suburb, with some casinos. That will make attracting certain kinds of residents more difficult.

Reilly contrasted our failure in this area with Arizona, which built a downtown campus for Arizona State University in urban Phoenix and connected it to the Tempe campus with light rail.

Muro of Brookings raises another transportation issue: The failure to better connect Las Vegas to both Phoenix and Los Angeles, and for that matter, Salt Lake City and Denver, has been a colossal failure. An interstate to Phoenix and high-speed rail to Southern California would help move tourists here and back. But it would also build commercial links to those cities, enticing companies to set up shop here.

Pull a Reagan and crush the local government unions

Local government employees, especially the unionized ones, have won impressive wages and benefits because of favorable collective bargaining rules, a state Legislature uninterested in messing with those rules and local elected officials who make a career of kowtowing to those unions.

Reilly, who dealt with the local unions for years at Clark County and watched helplessly as their salaries increased in the good times, says it’s time to roll back these costs to preserve needed services.

According to data compiled and analyzed by the Sun last year, the average firefighter in Nevada makes nearly $95,000, or 48 percent more than the national average. The average salary of a Clark County firefighter is $128,026, according to recent figures. Local police officers make nearly $79,000, or 30 percent more than the national average.

The salary levels create a tremendous burden on local government, especially during a downturn with no end in sight. The upshot is that layoffs of police, firefighters and other local government employees are inevitable.

“This means less services for people who need them,” Reilly says.

Save, save, save

“Debt is bad,” says Bill Robinson, a UNLV economist.

Our biggest gaming companies, including MGM Mirage and Station Casinos, took on massive debt, which nearly prevented MGM from opening CityCenter and pushed Station into bankruptcy. The result has been layoffs and real suffering for untold thousands.

Our own residents, meanwhile, were also in over their heads. This debt binge was a nationwide epidemic, but it seemed to find a special home here.

We all need to live like our grandparents taught us.

Bigger is not better

Robinson thinks we would be better off with many more small tourism companies as opposed to the rapid consolidation that consumed the industry in the past. Steve Wynn has voiced agreement.

Smaller companies, Robinson says, are more nimble, entrepreneurial and innovative, and often less weighed down with debt. (Although small companies borrowed too much, as well in recent years.)

Again, think of Detroit: One dominant industry, dominated by three massive companies.

Perhaps before Nevada regulators meet to rubber-stamp another merger, they might take a trip to Detroit.

•••

Can we do it? Can we learn from our errors?

Robinson is skeptical, even fatalistic.

“Have we ultimately learned the lessons? Only the next decade will tell. And my judgment is, of course we haven’t learned them.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy