Tuesday, Dec. 14, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sen. Mike Schneider

Sun archives

- Light-rail bill fails, but sponsor says idea still has life (4-14-2009)

- Stimulus bill paves way for road projects (4-7-2009)

- Planning for light rail, despite its high cost (4-3-2009)

- Train-like bus line on track for winter opening (3-25-2009)

- Sponsor of bill is also a beneficiary: Ho hum (3-5-2009)

- Bill introduced to bring light rail system to Clark County (2-3-2009)

- Senator wants light rail system in Clark County (8-25-2008)

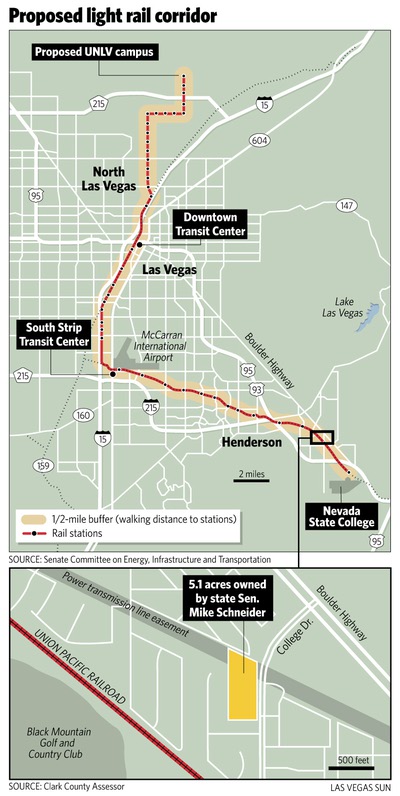

In 2004, Mike Schneider, a state senator with a long career in real estate development, began purchasing land in west Henderson, not far from Nevada State College.

He paid $885,000 for the first parcel and two years later bought a second from the city for $201,000. At that point, Schneider estimated, he could have sold the 5 acres for $7.5 million.

Then the market crashed.

Faced with a frozen equity market, plummeting land values and a virtual construction standstill, Schneider found himself holding the vacant land, as well as $1.65 million in debt he had accumulated buying it.

He turned to one of the only ways — albeit difficult and time-intensive — a private developer can make a profit these days.

As chairman of the Senate Energy, Infrastructure and Transportation Committee and vice chairman of the Commerce Committee, he is versed in the arcane world of government financing for low-income housing. Schneider also sits on the subcommittee tasked with ensuring the state spends its share of the $787 billion federal stimulus efficiently and appropriately.

Drawing on that expertise and his access to the state officials who run the programs he needed to piece together the money for his project, Schneider developed a sustainable condominium project for low-income senior citizens.

Schneider, D-Las Vegas, found an experienced developer, Joe DeSimone, and a couple of equity partners. Together they formed College Villas LP to build the namesake $24 million project set to break ground this month.

Schneider sold the land to his new partnership for $2 million — $400,000 more than the value determined by an appraisal a year ago. To purchase the land, the partnership tapped $3 million in federal stimulus funding for low-income housing.

With further help from a patchwork of government financing sources — stimulus money, federal loans, state and local grants, tax exempt bonds and tax credits administered through state agencies — Schneider is on his way to completing the development that is penciled to net the partnership an average of $1 million a year for the next 15 years.

The debt on his land is paid off, and he’s contracted to net $350,000 in cash for the land, once the project is making money.

Schneider said he didn’t set out to build a government-financed project. Instead, he said he was looking for a niche in a troubled market. He found it in senior housing.

That demographic is set to explode in coming years, as the number of units available for low-income seniors is limited, especially in Henderson, according to a market study by Applied Analysis in Las Vegas.

Schneider said he has gone through the lengthy and arcane process of obtaining government financing in the same way any private citizen could and has taken care not to let his position as an elected official influence the process.

His elected position has actually made it more difficult, not easier, for him to navigate the process than it would be for a private citizen, he said.

“I was actually a hindrance to some of these people as part of the deal,” Schneider said of potential investors. “It’s harder. Everyone has this thing about crooked politicians ... I would say it’s harder at every step.”

Schneider’s project has gone through a variety of government approval processes, at the county, state and federal levels, curtailing the state senator’s potential ability to use his elected position to influence the process.

But at least one low-income housing developer said the $2 million land price on the deal should raise red flags for underwriters, if not regulators.

The Las Vegas housing market has crumbled amid the recession. The availability of housing units is at a peak, while rents are plummeting. In such a market, apartment rents might end up lower than the capped rent Schneider’s project must offer under federal rules.

In these conditions, it’s difficult to put together a project — particularly one with a high land price.

Typically, low-income housing developers look for steeply discounted land, or respond to requests from governmental agencies that either own land or have found a way to provide land for the project at no cost or a substantial discount.

The $2 million land price in this case could have raised a red flag for the government and private equity investors underwriting the project, acknowledged Hillary Lopez, the housing division official who underwrote the stimulus award. But she said the land price didn’t seem out of line with the rest of the costs of the project when it was first presented.

“It would be (a red flag),” Lopez said. “But, part of it has to do with when the land was contracted for. Our market has changed dramatically. Some developers are under contract and locked into a sales price and unable to renegotiate.”

In fact, the sales price in the public file indicates $3.2 million, a figure DeSimone said the market could no longer support.

For his part, Schneider maintains he has taken a bath on the deal. “I’m taking a huge hit on the land is actually what I’m taking,” he said.

The partnership used its proceeds from the Tax Credit Assistance Program, which is part of the federal stimulus bill, to buy the land from Schneider.

DeSimone refused to provide a copy of the new sales agreement, saying it is part of the proprietary partnership agreement.

Schneider said he is carrying a heavy load of the upfront costs for the project, including significant application costs, the previous debt on the land, and a significant developer’s fee that under normal circumstances would have been paid to him and DeSimone upfront.

“This isn’t a get-rich-quick scheme,” he said.

Nearly all of the government financing for the project must be paid back by the development, at very low or no interest. The project is taking advantage of about $5 million in tax credits that don’t have to be paid back and a $350,000 energy grant from the state for a solar collector to power the common areas.

In a lengthy interview with the Sun, Schneider repeatedly said he took every step possible to avoid any conflict of interest and to keep an arms-length distance between himself and decision-makers.

DeSimone has done all of the communicating with the housing division staff, which regularly appear before Schneider’s legislative committee.

The housing division staff who underwrote the tax exempt bonds and who judged the criteria for awarding the stimulus money, however, were aware of Schneider’s involvement in the project. Much of the correspondence between DeSimone and division staff was copied to Schneider.

Housing division Director Charles Horsey also said he personally briefed Schneider on the various financing programs available through the division about two years ago.

Working to avoid the perception of a conflict of interest, Schneider also presented the deal to the Nevada Ethics Commission, which found the deal doesn’t violate laws restricting when lawmakers can enter into a contract with the state because it involves federal money.

He also discussed the deal with the Legislative Counsel Bureau, which gave him the go-ahead, he said. “I went and jumped through a lot of extra hoops to make sure I was absolutely clean like an altar boy,” Schneider said.

But there are gaps in Schneider’s transparency about the project.

Schneider said he didn’t disclose his involvement during a stimulus oversight committee meeting in October, even though his project was on the agenda.

“Did I disclose? Well, I disclosed that to (Assemblywoman) Debbie Smith (the committee chairwoman),” he said. “I said they’re reviewing that and the deal I’m working on is in there.”

Smith said she wasn’t aware of his involvement in the project that came before the committee, saying she might have had an informal conversation with him in the past. But a private conversation with the chairwoman of a committee doesn’t constitute a public disclosure.

Although the stimulus oversight committee reviews the spending, it has no power to control how the federal money is spent.

Schneider also didn’t mention that stimulus funding would be part of the project’s financing when he approached the Ethics Commission.

And he openly admits he worked to hide his involvement when the project went before the Nevada Board of Finance, which is headed by Gov. Jim Gibbons and approved the bonding.

Schneider has publicly criticized the outgoing Republican governor, who has had a contentious relationship with lawmakers during his term.

“I would not go into a meeting where Gov. Gibbons was because it would probably kill the deal,” Schneider said. “If he knew it was my deal, the son of a bitch would kill it. They didn’t know. There was no reason for them to know.”

Although Schneider didn’t attend the public meeting, his name was listed in documents given to the board, which reviewed the package to ensure the state wasn’t exposed to any undue liability through its involvement.

Gibbons’ spokesman Dan Burns said the governor is disappointed Schneider would hide his involvement.

Regardless, Horsey said the division is excited about the project. The agency has had a difficult time cultivating developers in Nevada with the experience and expertise to navigate the difficult process of building low-income housing.

“We would have wanted to finance the project despite his involvement,” Horsey said. “This particular project is such a good one to see that we would have financed it regardless of almost who was involved.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy