Ross D. Franklin / associated press

A light rail train pulls into downtown Phoenix for the first time during a 2008 test.

Friday, April 3, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Reader poll

Sun Archives

Southern Nevada’s transportation planners, exploring how to improve public transit, opted in 2006 for new rapid bus lines over a far costlier system of street cars gliding on rails.

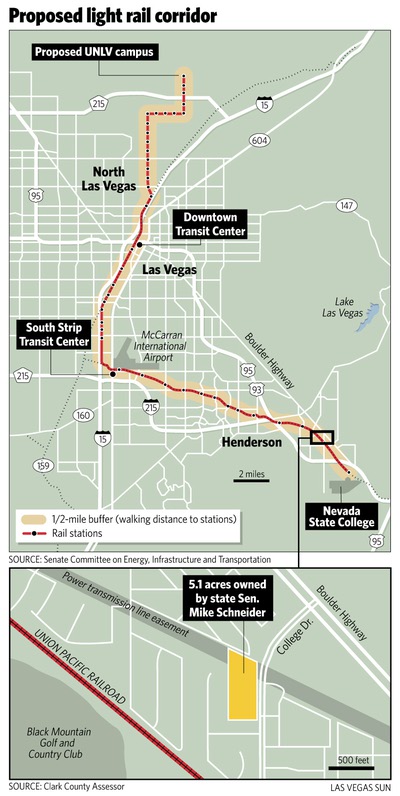

But now, state Sen. Mike Schneider is urging such a light-rail system — deep recession and declining government revenues notwithstanding. He is pushing state legislation that would require Clark County, Las Vegas, Henderson, North Las Vegas and the state transportation department to buy, “to the extent practicable,” rights-of-way (probably near Union Pacific Railroad lines) for “a fixed guideway” system, a dedicated route for light rail or buses. It would run from Nevada State College in Henderson through the resort corridor to downtown Las Vegas, terminating at a proposed North Las Vegas campus of UNLV.

The Las Vegas Democrat’s strategy may be shrewd politics. Urging local jurisdictions to buy land for the route would telegraph to the public that such a public transit system — he champions light rail — is inevitable as the region’s congestion worsens.

“We can’t dillydally anymore,” Schneider says.

Schneider thinks his bill — or a near duplicate sponsored by the committee he heads, Energy, Infrastructure and Transportation — would guarantee a fixed guideway system.

But the bill doesn’t set deadlines on how quickly local jurisdictions must comply. And the legislation seems to offer a loophole: The county or a city could decide it isn’t practical to spend the money on rights-of-way acquisition.

North Las Vegas City Manager Gregory Rose supports the bill but says he does not see it as a mandate to local governments. Henderson Public Works Director Robert Murnane says he interprets the bill as encouraging cities to buy rights-of-way when opportunities “come along.” Clark County spokesman Erik Pappa says officials are worried about the bill’s financial implications.

Littleton, Colo., spurred Denver’s popular light-rail system by buying rights-of-way for more than a decade before the system was formally planned and designed. Denver Regional Transportation District spokesman Scott Reed isn’t convinced Littleton’s actions assured light rail there, but believes that city sped the development of the commuter system.

“If you have opportunity to buy rights-of-way, you do it,” he says.

Cost is the largest impediment to light rail.

The Government Accountability Office, Congress’ investigative arm, says capital costs for rapid transit bus systems are $800,000 a mile when city streets are used and $16.4 million for dedicated lanes, whereas a mile of light-rail ranges from $15.1 million to $144.7 million.

Phoenix’s new, 20-mile light-rail system cost $1.4 billion, or $70 million a mile. That greatly dwarfs Southern Nevada’s first bus rapid transit line, the $52 million ACE Downtown Connector. But while the connector, opening this winter, has dedicated lanes downtown, buses will fight traffic when navigating the Strip.

Schneider’s timing may seem tone deaf — the state may cut basic services — but his bill coincides with a push by California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Pennsylvania Gov. Edward Rendell and New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg to invest nationally in America’s declining infrastructure, especially rail.

If Schneider’s bill fails, the proposed light-rail system will begin resembling the mirage that is the magnetic levitation train that would connect Las Vegas and Anaheim, Calif.: Discussion begets hope, only to be dashed by insufficient financial and political capital. Then a few years later the project is rekindled publicly, renewing the cycle. Maglev has been three decades in the making.

More ominous for light rail: The chairman of the California-Nevada Super Speed Train Commission figured two decades ago that maglev was a few years from operation. The project has barely budged since.

That’s why it’s in the best interest of light-rail proponents to get Schneider’s bill through the Legislature. (A hearing on the bill was postponed Thursday.) There would be the perception of progress. And then supporters could contend the project isn’t pie-in-the-sky, but inevitable — at least based on Denver’s experience.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy