Zyber Selimaj reenacts the pose, on his knees with his hands up, that he says his wife Deshira took before she was shot and killed by Henderson Police officers at the scene of a traffic stop near Coronado High School.

Thursday, Feb. 21, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Contradicting Stories Arise in Henderson Shooting

The Henderson Police Dept. held a press conference Feb. 21 to address various news reports surrounding the shooting death of 42 year-old Deshira Selimaj. The press conference offered a different account of the scene than that of eyewitnesses, and the report also presented contradicting facts from what the department released the day of the shooting.

Audio Clip

- Zyber Selimaj talks about his wife not having a knife.

-

Audio Clip

- Zyber Selimaj on what his wife said about police wanting to arrest him.

-

Audio Clip

- Zyber Selimaj on his wife getting shot in front of their kids.

-

Audio Clip

- Zyber Selimaj on hearing his wife was dead.

-

Sun Archives

- Woman dies from officer-involved shooting (2-13-2008)

- Face to Face: The Final Take (2-13-2008)

Beyond the Sun

Of this fact, Zyber Selimaj is certain: No matter what Henderson Police say, his wife was not carrying a knife when an officer shot her last week, killing her next to the ice cream truck she drove for a living, and in plain view of her children.

Even in the hazy wake of his wife’s death, this detail is clear in Selimaj’s mind. And not just kind of clear, he says, but crystal. She was not carrying a knife, never carried a knife in her truck and never, as the police also claim, held a knife to the neck of one of her three children in the moments before she was killed.

So at least one fact is absolutely indisputable: The police and the father have very different versions of what happened.

That’s one of the reasons why Selimaj agreed to the Sun’s request for an interview at his Henderson home. He and his wife bought the house four months ago, after living in a trailer for several years.

The new house is now full of funeral floral arrangements.

Along the doorway five pairs of shoes are lined up, small to large. Selimaj, 65, hasn’t moved his wife’s purple flip-flops. Guests, however, are no longer instructed to remove their shoes before coming in.

“Mom is dead,” Selimaj said, so you don’t need to worry about the white carpet, or any formalities, really. Not anymore. “There is no woman here.”

Still, their boys, ages 5, 7 and 11, were trained to hug guests when they come in, and so they do, half-smiling. Then they cluster on the couch, an overstuffed green brocade, and play a hand-held video game while their father recounts the day in question. He talks, and cries, over a background of video game blips.

When Selimaj keels over onto the carpet to reenact his wife’s death, the children put down the game and chew their nails.

Selimaj came to America in 1992 after spending 22 years in an Albanian prison, sentenced for speaking out against communism in his native country. He came to Nevada to carve out a suburban life. The family’s two ice cream trucks, the entire fleet of the Deer Runner Albania ice cream company, are parked at the end of the driveway in the neighborhood cul-de-sac, white wagons plastered with yellow stickers against a backdrop of dry desert brown.

Selimaj said he left the house driving one of the trucks about 11:30 a.m. Feb. 12. He was headed toward the Henderson neighborhoods where he sells ice cream when he was pulled over by a police officer for failing to come to a complete stop. The officer let Selimaj slide on that violation, but he wrote him a $67 ticket for not wearing a seat belt.

Selimaj called his 42-year-old wife, Deshira, who was at home with Alban, 11, and Arber, 5. Their third son, Azbi, 7, was in school. Selimaj told his wife he hadn’t sold any ice cream and he already had gotten a ticket. She told him, “Don’t worry, be careful, drive slow.”

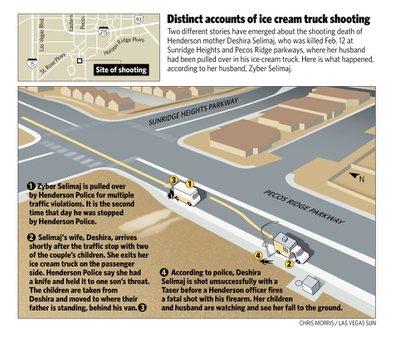

By 2 p.m. that day, Selimaj was nearing Sunridge Heights Parkway, a road that runs alongside medical buildings and tract homes and then passes Coronado High School. It was in this neighborhood that Selimaj was pulled over again, for failing to stop at a stop sign and for speeding in a school zone, a charge he contests. This time, Selimaj said, a police officer wrote a citation that carried a $650 fine, and Selimaj initially refused to sign it.

Everything that happens thereafter is open to debate.

Selimaj admits he was upset. He says he asked to be let go so he could sell his ice cream. Paying a $650 ticket “means I am working for police,” he said, “not for my kids.” Selimaj said the officer told him that if he did not sign, he would go to jail. Selimaj told the officer he’d rather go to jail. He’s been to jail before.

According to a police news release, the responding officer believed that a language barrier was preventing Selimaj from understanding him.

Selimaj said the officer told him to calm down. Selimaj replied that he would calm down just as soon as he could call his wife. He dialed Deshira, who was at home, cleaning up juice that Arber had spilled in a second-floor bedroom.

Deshira was always cleaning, Selimaj told the Sun. “She was a neat woman,” he said. “An excellent woman.”

When Deshira answered the phone, Selimaj told her he was going to jail.

“Again?” she said. “Now jail in America?”

She became upset. The officer, Selimaj said, caught the tone of their voices but didn’t understand the words because they were speaking Albanian. The officer asked to talk to Deshira, so Selimaj handed over the phone. Selimaj has no idea what his wife said, but the result was that the officer forced the phone back at him, irritated, and said he didn’t want to talk to Deshira any longer.

Deshira’s English, the family agrees, was much better than her husband’s.

Deshira told Selimaj she was going to him. She grabbed Alban and Arber, put them in her ice cream truck and started driving to the neighborhood where he had been pulled over. Police say they did not ask her to come, and it’s unclear whether they expected her to show up. She got there about 20 minutes after she was called, Selimaj said, and by the time she arrived Selimaj had signed the ticket.

The police officer, the same officer who was concerned about a language barrier, said after Selimaj signed the ticket he became confrontational and made suicidal statements.

Selimaj denies this.

When Deshira pulled up, she and the children saw Selimaj sitting handcuffed on the ground, where he says officers asked him to wait. Looking worried, he said, she clambered out of the passenger-side door, children in tow.

As soon as she was out of the truck, Selimaj said, two Henderson Police officers drew their guns and pointed them at the mother.

This is the beginning of another serious discrepancy in the stories.

Selimaj said the police grabbed the two children from Deshira and thrust them toward him, so they ran to their father. He said police had Selimaj and his sons behind his ice cream truck. The three of them say they leaned around the corner of the vehicle and saw Deshira on her knees, flailing her arms above her head, wailing.

Then they heard a loud bang, Selimaj said, and saw Deshira fall forward onto the concrete.

Selimaj pantomimes this fall in his living room. He raises his hands in the air, waves his arms back and forth, wails and then pitches forward onto the floor. Then he comes up, like a swimmer for air, and gasps.

After they watched their mother fall, Selimaj said, the children began sobbing. Before police could separate the father and his children, he bent forward and kissed them on the head, since he was handcuffed and could not hug them. The children were then placed in county custody at Child Haven while he spent two days in jail.

No more than a few minutes passed between the time Deshira showed up with the boys and the time she was face down on the ground, Selimaj said.

The Henderson Police version of what happened is significantly different.

They say Deshira showed up in the ice cream truck with the boys, got out, and then reached for a knife inside the vehicle. Police say she held the knife to one of the boys’ throats and made suicidal statements to the officers. Police say they got the boy away from Deshira, but could not get her to drop the knife.

Two officers then attempted to use their Tasers on Deshira, but “their efforts were not successful,” according to a news release. While holding the knife, Deshira made aggressive movements toward an officer who, fearing for his life and the lives of those around him, shot her, Henderson Police spokesman Keith Paul said.

Deshira was taken to Sunrise Hospital, where she died.

At the Henderson jail, Selimaj said, three officers told him, “Be strong, your wife is dying.”

Seven days later, and Selimaj is emphatic: His wife had no knife. In fact, when he kept a kitchen knife in his truck for cutting fruit, she’d scolded him.

Neither Selimaj nor his children recall seeing Tasers, either.

Through the family’s attorney, Jim Jimmerson, Selimaj has hired private detective Hal DeBecker to seek witnesses, many of whom spoke to the TV reporters who descended on the scene of the shooting. The witnesses, however, did not allow their faces to be shown or their names used, so DeBecker doesn’t know whom he is searching for, only that he has to find them.

Those witnesses agreed on one thing: Deshira didn’t have a knife.

Police say they have the knife and what really happened that afternoon will all come out at the coroner’s inquest, set for April 11. The officer who shot Deshira, 23-year-old Luke Morrison, has been with the Henderson Police for two years and is on paid administrative leave while the shooting is investigated.

Deshira’s family, also from Albania, landed in Las Vegas on Tuesday. Her father would not let Selimaj bury her body until he saw her.

This detail sends Selimaj into another spasm of tears.

“I cry, I cry, I cry,” he said. “I pull my hair and cry.”

Eleven-year-old Alban who, like his brothers, was born in the United States, sits by his father, looking vacant and saying little.

Alban said he did not hear the police say anything to his mother before they shot her, but he heard what she shouted at them: “Leave me alone, leave me to raise my kids.”

He says this, then asks to be left alone. He flees to an upstairs bedroom where his brother and the children from other Albanian families, who keep floating in and out of the home, are playing and eating popcorn.

Taped above the microwave, there’s a pink card that reads: “Happy Velentines. I love you Mom.”

Selimaj stays in the living room with his brother, Ray, who flew in from Texas on Tuesday to help and can only wander about the living room, wringing his hands, like everybody else.

Quietly, standing on the carpet in his shoes, Selimaj says, “Even in communist Albania police never kill a mom in front of her children.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy