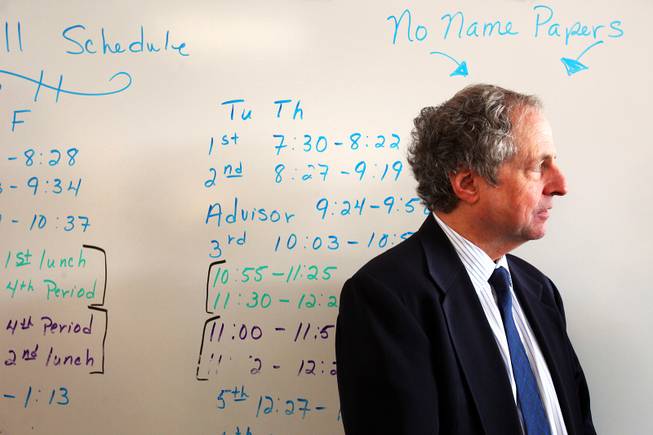

Joe Barison, the regional director of the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Communications and Outreach, tours Mojave High School campus with principal Antonio Rael in North Las Vegas on Thursday, April 12, 2012.

Monday, April 16, 2012 | 2 a.m.

What is a turnaround school?

The Clark County School District implemented the "turnaround" model at five of its worst-performing schools for the 2011-2012 school year. Four of these schools — Chaparral, Mojave and Western high schools, and Hancock Elementary School — received a piece of $8.7 million in federal School Improvement Grant money to improve test scores and for the high schools, graduation rates. As part of the turnaround model, the principal and at least half of the staff were replaced at each school, and schools were required to implement new programs and teaching methods to improve student achievement.

Related story

- Mojave’s ‘Breakfast Club’ hopes to teach life’s lessons to students (2-2-2012)

- At Mojave High, program for misbehaving students is detention hall on steroids (2-14-2012)

- Personal touch and attention to detail helping Mojave move beyond troubled past (11-26-2011)

- At tarnished Mojave High School, seniors eye new direction with optimism (10-9-2011)

This is another in a yearlong series of stories tracking efforts by the Clark County School District to improve student performance at five struggling schools.

Joe Barison came to town last week to poke around, curious about the status of the turnaround process in Las Vegas schools.

After the federal government sent $8.7 million in stimulus funds to raise student achievement in four of Clark County’s poorest-performing schools, Barison wanted to know if it has helped.

The director of communications for the U.S. Department of Education’s southwestern region turned his eyes toward Mojave, a North Las Vegas high school with a 50 percent graduation rate and the valley’s lowest test scores.

A communications professional, Barison wasn’t exactly interested in student data, however. He’s leaving testing benchmarks, graduation rate calculations and other number crunching to state and federal colleagues who have been conducting monthly compliance checks.

Instead, Barison wanted to focus on the human effects of the federal government’s grand experiment.

To receive $2 million in federal School Improvement Grant funding, Mojave enacted the “turnaround” model this school year, meaning the principal and at least half the staff were replaced.

To call it a radical move would be an understatement.

Educators were upset and students saddened by the prospect of losing their favorite teachers. Hundreds of students at Chaparral High School — another “turnaround” school — revolted, protesting the drastic mandates accompanying the grant.

Nearly a year later, Barison wondered: How have Mojave teachers and students dealt with the changes? Is Mojave a better school?

As he toured the school with Principal Antonio Rael — popping into classrooms and getting a feel for Mojave — Barison saw a clean and orderly campus.

Graffiti-ridden bathrooms and walls that characterized the old Mojave have been expunged of the blight. Students were busy studying quietly in classes instead of walking out at random, which occurred regularly a year ago. Fights — almost weekly occurrences last year — have decreased substantially, Rael said, noting that when he first stepped foot on campus, he saw three fights break out within 20 minute.

“This was a campus out of control,” Rael told Barison about the old Mojave. “It was a train wreck.”

The new Mojave still has plenty of room to improve, Rael said. The number of drug incidents — a stubborn problem in many Clark County high schools — has remained high. More than 300 seniors still had one or more proficiency exams they needed to pass in March to graduate. (Those results will be released this month.)

Still, there have been academic gains among the 2,000 students, 85 percent of whom are minorities and 60 percent of whom receive free or reduced-price lunches, Rael said. The school has made all of its first-year testing benchmarks, except among its special-needs students in English. Mojave is also on track to graduate a record number of students.

Barison said he was impressed by the changes at Mojave, the second turnaround school he’s visited and the first in Nevada. He said he was especially happy to see Mojave had begun to cultivate a culture of education driven by student data.

“It’s obvious that Mojave’s leadership is committed and cares about its students,” he said.

However, Barison wanted to dig deeper. He summoned two teachers and two students to a conference room to talk candidly and individually about the effect of the federal School Improvement Grant.

It’s all part of a departmentwide missive by Education Secretary Arne Duncan, Barison said, “to find out how people are responding to the federal grants, and what it means in people’s day-to-day lives.”

“I’m interested in the people side of the SIG story,” Barison said. “Arne Duncan has said many times that the most helpful knowledge about education and solutions is going to come from the classroom — from educators, teachers and students. Very few answers are going to come from Washington, D.C.”

So Barison listened, and got an earful — of optimism, hope and signs pointing to a better tomorrow.

Mojave senior Jesse Torres gave a resounding endorsement of Mojave’s turnaround. Torres is on track to be the valedictorian of his class and was recently accepted at the University of Southern California.

“I feel it’s better now that the environment has changed,” Torres said, noting that his new teachers seem to care more about students. “It feels much safer than before.”

English teacher Kevin Joseph Mills said he’s seen big changes at Mojave since he arrived on campus six years ago. The new principal, Rael, has availed himself to teachers and students, Mills said, creating a welcoming environment of fist-bumps, high-fives and cheery “good mornings.” These richer relationships between educators and students are making a difference socially and academically, Mills said.

There have been fewer fights and less profanity around campus, he said. Mojave’s had a rough history with guns being found on campus and students being arrested for crimes from vandalism to murder, he said.

“I don’t feel the tension as it used to be,” Mills said. “Students can’t learn if they don’t feel safe.”

Rael said he was proud to showcase his school’s turnaround efforts to Barison, who plans to share his findings with supervisors in San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

Nationally, there have been talks of defunding the School Improvement Grant program as critics have questioned the effectiveness of the turnaround process. It’s too early to tell if it has worked in Las Vegas, but early indications are that Mojave is on track, Rael said.

Rael credited Mojave’s progress to the hard work of teachers and the SIG funding, which allowed for a longer school day and additional compensation for teachers.

“It’s really hard work at a turnaround school,” he said. “This funding has been absolutely paramount to our early successes.”

Mojave High School is Rattler Nation, but really it’s home to underdogs.

Minutes from the Nellis Air Force Base the school is nestled near Commerce Street and West Ann Road, an area littered with foreclosed homes.

The school is attended by many students who are underprivileged or at-risk. After Mojave failed to meet No Child Left Behind standards it became one of five Clark County Schools determined to do a 180.

In order to make the turnaround a reality, Mojave has implemented new faculty, extended the school day by 20 minutes and is geared towards boosting school spirit.

“The problem we have right now is that our children aren’t proud of their own school,” Mojave principal Antonio Rael explained an August interview. “When our children begin to take pride in our school, our community will follow.”

- Year built:

- 1997

- Mascot:

- Rattle Snake

- Principal (Year Hired):

- Antonio Rael (2001)

- School motto:

- “Promoting Achievement, Creating Success”

- Mission Statement:

- “The Mission of the Mojave High School Community is to provide a safe learning environment that will empower students to develop excellence, pride, respect, and skills necessary for future success.”

- Enrollment:

- Approximately 2,000

- School Report Card:

- 2010-2011

Compiled by Gregan Wingert

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy