AP Photo/Charles Dharapak

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, accompanied by Sen. Christopher Dodd, D-Conn., speaks about financial reform, Wednesday, April 28, 2010, on Capitol Hill in Washington. Reid is one of three senators calling for more federal enforcement agents and other border security-tightening benchmarks.

Sunday, May 2, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sun archives

- Planned wind-turbine plant gathers gust of momentum (4-28-2010)

- Plant to bring green-job windfall (3-12-2010)

- Companies announce plans for wind turbine manufacturing plant (3-11-2010)

- Only Nevada to blame for puny share of U.S. money (3-10-2010)

- Energy Department withdraws application for Yucca Mountain (3-3-2010)

- Obama to announce new foreclosure rescue program in Las Vegas (2-19-2010)

- Harry Reid cuts Medicaid deal for Nevada (9-22-2009)

The heart of Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid’s argument for re-election is that he is a powerhouse who delivers for Nevada like no one else.

Reid brings home more money than the state’s other four Washington lawmakers combined. But that fact may be lost in neighborhoods ripped by joblessness and foreclosures.

Indeed, in a state laid low by the Great Recession, Republicans are trying to find currency in asking: What has Reid done for Nevada lately?

It’s a question Reid has only awkwardly addressed. Never mind that his haul from earmarks alone contributes almost $240 million a year to Nevada. Stated another way: That’s more than eight times the annual state revenue from mining taxes or one-third its take in yearly gaming taxes.

Yet Reid’s Republican challengers, including front-runner Sue Lowden, routinely ridicule Nevada’s ranking as 50th in the nation in federal funding per capita coming to the state.

The response from Reid’s team devolves into a turgid trudge through federal funding formulas that leads to glazed-over eyes.

As Reid launches what is likely his final campaign, his fate might be decided by perceptions of his effect statewide since his last election in 2004, when he ascended to Democratic leader.

Put another way, how will voters answer this question: Has Reid used his position as arguably the second most powerful Democrat in Washington to help Nevada, or would the state be better served by a leader who does not play on the national stage and keeps to work closer to home?

Out of his hands

Criticizing Reid for the amount of federal dollars he brings to Nevada isn’t a new line of attack. Republican John Ensign used it in TV ads during his 1998 Senate race against Reid.

But the issue forcefully resurfaced in early 2009 with the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, known as the stimulus bill, aimed at blunting the effects of the recession by shoring up state budgets, cutting taxes and providing money for road and other projects. The argument, voiced by Reid’s challengers: When Nevada was hurting, the powerful majority leader couldn’t prevent it from being at the bottom in per capita stimulus dollars flowing to the states.

“It is absolutely humiliating,” Lowden’s campaign manager Robert Uithoven says. “Our senior senator brags about being the most powerful leader and yet he gives more money to ACORN (the liberal community organizing group) than he does to the state of Nevada.”

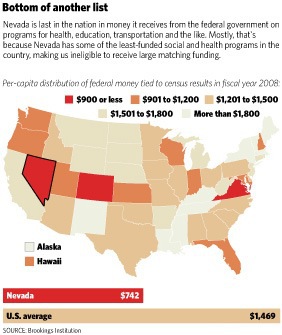

Yet Nevada’s ranking in stimulus dollars should come as no surprise. It has long been near the bottom in federal funding returned to the state. This is primarily because the federal government requires states to pony up matching funds and Nevada has time and again failed to do so, leaving federal money on the table.

Andrew Reamer, a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, concludes that the biggest roadblock to Nevada receiving more money from the feds is its unwillingness to spend on social programs, in particular Medicaid, the health program for low-income people.

Nevada brings in $742 annually per capita — barely half the national average of $1,469, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures compiled by Brookings.

Reamer said almost 80 percent of the discrepancy in Nevada’s federal haul and the national average is that Medicaid gap. Because Nevada operates one of the stingier Medicaid programs in the nation, it is losing out on federal funding claimed by other states.

For example, Nevada brings in $286 per capita in federal Medicaid funding, while Vermont, which provides more generous coverage and serves a greater share of its population, receives $1,916.

“That’s a state government decision,” Reamer says. “That’s not a Harry Reid decision.”

In transportation, the next-largest category of federal funds coming to Nevada, the state does better than the rest of the nation, collecting $168 per capita compared with the national average of $158.

Other top funding categories — welfare and education — are distributed based mainly on poverty levels. Nevada, until recently, had a higher income level and thus did not receive as much aid as other states.

Lowden’s camp likes to say that Nevada was better at bringing home federal dollars before Reid took office — ranking 33rd in 1986 and receiving 98 cents for every $1 sent to Washington, compared with 65 cents in 2005.

But in fact, 1986 was the only year from 1981 to 2005 that Nevada crept above 40th in state standings for federal money per capita, according to the Tax Foundation, Lowden’s source. (Reid took office in 1987.)

Furthermore, by 2008, Nevada brought in 97 cents for every $1 sent to Washington.

Creating jobs, industry

In these hard times, Reid’s critics say, he should be using his clout to tilt federal funding formulas to Nevada’s favor.

That’s what Lowden says she would do. If elected, she says she would pursue a post on the Senate Finance Committee — a plum assignment that Republican Sen. John Ensign received after his second term in office. She has also vowed to hire a “junkyard dog” to go after federal funds.

Yet a federal lawmaker can only do so much when his or her state will not pony up matching dollars — and Ensign has not been able to change the inequities he campaigned on fixing.

Reid has, however, used his position as majority leader to change some formulas to Nevada’s benefit — often with a phone call or a pen stroke.

• In the stimulus bill, Reid tweaked the federal Medicaid formula to get Nevada the largest percentage increase of any state — sending $450 million home.

• He upped the amount rural areas receive from Payments in Lieu of Taxes, or PILT, on undeveloped federal lands. Elko County Commissioner John Ellison said those dollars have provided one of the most important rural safety nets during the recession. “Without PILT, some of these counties out there would have never weathered this,” said Ellison, a Republican running for the Assembly who has not endorsed a U.S. Senate candidate.

• Reid ensured that Nevada received the largest per capita allotment of foreclosure aid with $1.5 billion for five hard-hit states in a new housing rescue program announced when President Barack Obama visited Las Vegas in February. Nevada will receive more than $100 million.

Where Reid is most effective in making gains for Nevada often goes unseen, his supporters say, because it happens behind the scenes.

Last year, he inserted in the stimulus bill a massive prize for his home state — $3.2 billion for an obscure Western federal power agency, which is now providing low-interest government loans to finance Nevada’s first north-south electrical transmission line.

In addition to the immediate construction jobs, the long-sought $550 million line is expected to attract renewable energy companies and make it possible for energy generated by renewable projects to be sent statewide and eventually exported. Reid’s office handled crucial negotiations to seal the deal.

Reid’s spokesman Jon Summers notes the 1,000 jobs created by a new wind turbine manufacturing facility in Southern Nevada are the start of the state’s green economy. Building the transmission line will create 400 construction jobs.

“He is creating a new industry that Nevada will have forever,” Summers says.

Lowden’s campaign may be trying to have it both ways, saying at first that Reid doesn’t bring home enough money and then saying she prefers tax cuts so less Nevada money goes to Washington in the first place.

Lowden argues private industry, not the federal government, would do a better job at rescuing the economy and spurring growth.

For example, she thinks the electrical transmission line should be financed primarily by energy companies and their ratepayers, and not federal taxpayers.

“You don’t have to get more from Washington; you can send less in the first place,” Uithoven says.

How Yucca Mountain can hurt him

Nevada has long had an uneasy relationship with Washington, touting rugged Western individualism even as it has relied on the federal government to divert its rivers for farmland, build roads and give away public land for gold mining.

This sometimes-contradictory philosophy complicates Nevada’s relationship with Reid, whose big-ticket accomplishments can be double-edged swords that win him as many foes as friends.

For example, Reid’s efforts to engineer the massive pipeline plan to draw eastern Nevada water to Las Vegas have been demonized by ranchers and others who oppose the water grab. (Similar water wars haunt Reid in the north, where he worked to divert water to save Pyramid and Walker lakes.)

Many White Pine County residents are upset that Reid stopped the proposed coal plants they saw as jobs generators.

Environmentalists, meanwhile, are furious his support of the mining industry blocks their best chance in a generation to impose national mining royalties and restrictions.

One of Reid’s high-profile accomplishments since he became Democratic leader, bringing the proposed nuclear waste dump at Yucca Mountain to the brink of extinction, has infuriated those who see the repository as a potential source of employment. During Reid’s spring bus tour through rural Nevada, neither he nor his campaign mentioned the dump much.

Reid accepts the animosity some of his work has engendered with a shrug, believing he is charting Nevada on the best course forward.

“Some of the counties I get the lowest votes I’ve done some really great things (for),” Reid said while touring rural counties. “People say ‘why are you trying to help Fallon?’ Because it’s the right thing to do.”

The Washington, D.C., angle

Up for conjecture is whether Reid would have been more closely tuned to Nevada had he not been the Senate Democrats’ leader for the past six years.

His position in Washington gives him access and influence, even in state affairs 2,400 miles away. Sun columnist Jon Ralston sometimes calls him the “meddler in chief.”

Yet upon the Democrats becoming the majority party in the Senate in 2007, Reid gave up the gavel on an important appropriations subcommittee, which can be a resource for handing out funding. He previously surrendered his seat on other committees.

Some imagine that if Reid hadn’t been distracted by his leadership duties, he might have led the effort to diversify Nevada’s economy, creating a Las Vegas that was not so dependent on tourism and gaming. They envision Reid bringing a federal landmark project to the state — a renewable energy lab on par with the scientific labs in New Mexico or California — that could bring jobs and professional expertise to a state that lacks both.

But others say these scenarios ignore decades of inertia.

“This is Nevada’s lack of foresight for decades,” says Eric Herzik, chairman of UNR’s political science department.

“He can be criticized, sure, but it’s not just Harry Reid. You can blame Bob Miller, Kenny Guinn, Mike O’Callaghan,” he says, listing past governors. “Nobody developed that bigger picture.”

Reid’s team says the senator is doing more as Senate majority leader than any single senator could — helping steer the state through difficult times from his Capitol office. They cite the constant stream of everyday efforts such as the $23 million he secured recently for transportation projects in Las Vegas.

With a phone call Reid can reach the highest levers of power in Washington and has done so to bring Cabinet and other administration officials to Nevada — gestures state leaders say make a difference.

Even Republicans in Nevada who hate Reid’s national political profile readily admit he is the one they turn to when they need something done.

Tom Fransway, a Republican Humboldt County commissioner whose daughter, Reagan, is named for the 40th president, says “I can tell you I don’t agree with everything the senator does but, nobody can deny what he has done for the state of Nevada.”

When Northern Nevadans fought changes in mining law or sought to ensure cattle ranchers had public grazing lands, they turned to Reid, he said. The senator’s work securing $20 million for Western states to fight the Mormon cricket infestation was no small favor, Fransway said.

“Some may call it an earmark, but when you’re up to your ankles in those bugs that are 2 inches long and nasty — and they make the freeway so slick cars slide off it, and it’s unpleasant — it’s certainly not an earmark for us,” Fransway said.

Reid’s supporters counter questions about what might have been had he not become majority leader by asking what national policies the state would have lost had Reid not become the top Senate Democrat. They argue health care reform would not have become law without Reid’s leadership. Also, Reid can shuffle the Senate calendar when it helps Nevada, as he did to ensure passage of a travel promotion bill that the tourism industry thinks will help boost foreign visitation.

“I think some of this criticism is unfair,” says Herzik, offering this hypothetical conversation:

“‘You should have brought more.’

“‘OK, what should I have brought?’

“‘Well, you know, more.’”

In many ways, Reid’s poor showing in public opinion polls might be the product of a state that leaned on him during the boom years to bring home the bacon to support growth and now asks why he cannot suddenly do the same to fix Nevada during the bust.

One Nevada policy analyst, a Democrat, says that as the Great Recession drags on, there is a growing realization that even the meddler in chief cannot single-handedly turn Nevada around.

“He’s the majority leader,” the analyst says. “He’s not God.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy