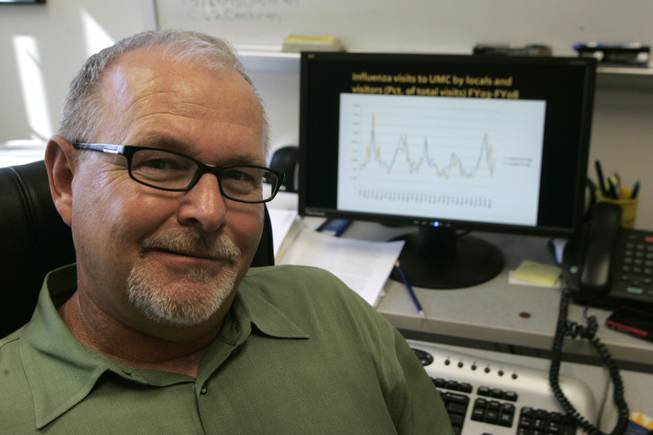

UNLV researcher Chris Cochran is working on a project for the U.S. military, which hopes to track the source of illness among its troops.

Friday, April 23, 2010 | 2:01 a.m.

Tracking tourists

Researchers are working on computer models that can track tourists who contract a virus and wind up in Las Vegas hospitals. Las Vegas works well as part of the military study because millions of tourists pass through each year, and there are only few ways in and out of town — similar to travel patterns of soldiers entering and departing limited access points of war zones. The more data researchers can get on the source of a pathogen, the quicker officials can halt its spread.

Sun coverage

A multimillion-dollar research project involving UNLV is aimed primarily at better protecting U.S. troops, but it is also expected to shore up the Las Vegas Valley’s defenses against epidemics and bioterrorism.

UNLV Associate Professor Chris Cochran is helping lead the effort and hopes it will help hospitals and public health officials do a better job of quickly identifying the sources and pathways of influenza, E. coli and other contagious pathogens that can quickly spread through a population.

Suppose Clark County health officials learned that a group of tourists who came down with the flu in Las Vegas arrived by plane the previous day from Anytown, USA. Because symptoms don’t usually appear until two or three days after infection, it’s likely the tourists contracted the virus back home. Health officials could then issue flu alerts to authorities in Anytown and to the airlines that brought the visitors to Las Vegas to help prevent a more widespread outbreak in Southern Nevada.

Or say the tourists who sought medical attention in Las Vegas had been in town a week before their flu symptoms appeared. It is then more likely they caught the virus in Las Vegas. If health officials knew that these patients were staying at particular hotels, the resorts could be contacted to locate potential sources of the virus so that it can be contained, thereby protecting other hotel guests and workers.

This is the kind of detailed information Southern Nevada health professionals would be able to obtain if Cochran, a member of UNLV’s School of Community Health Sciences, and Defense Department contractor QinetiQ North America succeed in developing computer software that is being sought by the U.S. Army.

The 3-year-old project is expected to last at least two more years under the guidance of QinetiQ (pronounced “kinetic”), a subsidiary of a London-based company with offices in Las Vegas. So far, $3.6 million in military spending has been appropriated for the project.

The Pentagon is involved because it has a stake in knowing the source of illness among its troops. It wants to know whether the source was on a particular ship, military base, battlefield location or somewhere else that needs to be addressed. The military also wants to guard against unwittingly spreading a disease when soldiers return home.

The 1918 “Spanish flu” pandemic was first observed in the U.S. at the Army’s Fort Riley, Kan. In 1976, when swine flu was first identified, it was at another Army post, Fort Dix, N.J.

The research in Southern Nevada, officially known as “Bio-surveillance in a Highly Mobile Population,” “is all about the potential for more timely and targeted intervention during an outbreak or bioterror attack,” says Nick CerJanic, a QinetiQ director in Las Vegas. “The financial impact, and much more importantly the human toll of a life-threatening virus or an aerosol anthrax attack, increases exponentially with time.”

To simulate the limited war zone entrances to and exits from Iraq and Afghanistan, Cochran and QinetiQ are working on computer models that aim to track tourists who wind up in Las Vegas hospitals. Las Vegas is a natural for the study because tens of millions of tourists pass through annually, and there are only a handful of ways they get in and out of town.

So far, the researchers are focused on tourists who exhibit flu-like illnesses while in town.

“The reason we’re using influenza-like illnesses is that we are going to see far more cases of that than we are rare diseases,” Cochran says. “The greater the volume of data the more you can confirm the validity of the model you are trying to use, so that we would be able to use it down the road to track a rarer disease.”

Since last fall, Cochran has been receiving data from University Medical Center on everyone who has gone to the hospital. The data is limited to the patients’ ZIP codes and ailments, together with patient codes assigned by the hospital that mask the identities of those individuals from the researchers. Cochran and

QinetiQ, in other words, have no way of identifying patients by name or address.

ZIP codes give them an idea where patients come from, which is helpful in attempting to isolate the source of a virus attack. This is particularly true in cases where there is a cluster of individuals from proximate ZIP codes.

“This could help every health organization in town if we see spikes,” says Jim Poulos, UMC’s director of application development and support. “You might be able to prepare supplies and staff for an increase in patients.”

Cochran is hoping that Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, Valley Hospital Medical Center and other Southern Nevada hospitals agree to participate, too. The more data gathered, the greater chance that the researchers will succeed.

Researchers are also seeking resorts’ participation. They would like to know which hospitals the resorts send hotel guests to when they get sick and the nature of those illnesses. This could help determine whether a particular hotel was the source of the outbreak or whether the viral disease emanated from somewhere else.

Resorts are hesitant, to say the least, because they don’t want the reputation of playing loose with their guests’ privacy and don’t want to be identified as the site of infection.

Cochran is optimistic that they will come around, though.

“We’re sensitive to the confidentiality issue,” he says. “We also know that the information has to be provided in a way where it can benefit the hotels in terms of not only keeping their visitors safe but their workers, too. It would be good for the hotels to participate because the quicker they know something is going on, the faster they can make corrections.”

Researchers are also trying to compile what is known as social modeling data to estimate the number of people a typical tourist comes in contact with while in town — in an elevator, at a card table, walking the Strip, at a show, in a bar.

Likewise, Cochran and his QinetiQ teammates would like to collect passenger information from airlines to give researchers the ability to tell whether an outbreak could be linked to a particular flight. The whole point is to trace the path of the virus.

“Tourism professionals in Las Vegas already invest significant resources to ensure the health and safety of our visitors,” CerJanic says. “Both UNLV and QinetiQ North America expect to leverage the results of this project to benefit the vital industry of Las Vegas to better protect their guests and workers.”

UMC shares certain early-warning information on contagious diseases with the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the CDC’s BioSense program, a national health surveillance network. This network identifies the existence of outbreaks in specific communities but not the source of the virus or the paths it took to reach a particular city, as Cochran is seeking to accomplish.

“There are some problems with BioSense in terms of how well it really drills into the information that it has,” he says. “What we want to be able to do is to drill further into the data so we can find where the people came from. The more information we can gather on tourists the better.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy