Sunday, Sept. 20, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Coverage

Sun Archives

- Nationwide tour promoting health care reform ends in Las Vegas (9-18-2009)

- Desperate for insurance, residents share health care woes (9-18-2009)

- Harry Reid: Health care bill won't work for Nevada (9-16-2009)

- Grant to aid 400 waiting for Medicare (9-14-2009)

- Editorial: Lowering Medicare costs (9-2-2009)

- Medicare Advantage plans may lose federal cash (1-16-2009)

With a greater percentage of uninsured residents than most states, Nevada faces a key question arising from the health care debate: At what price is the state willing to expand its coverage of the poor?

Would the state pony up a nickel to gain an additional $1 in care if the federal government paid the difference? How about a dime? Or 18 cents?

For cash-strapped Nevada, it’s a vexing question — one that has set off a feud between the state’s Republican governor, Jim Gibbons, and its top Democrat, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, both of whom face tough reelection battles next year.

Under the health care bills before Congress, state Medicaid programs, which now primarily cover low-income children, parents, seniors and people with disabilities, would be expanded to include a new segment of the population — poor, childless adults.

The group makes up 21 percent of the uninsured nationwide, and a slightly larger share in Nevada. Many of them are poor, which the government defines as individuals making less than $14,400 a year.

With nearly 470,000 uninsured in Nevada and a soaring jobless rate adding to those ranks, uninsured, childless adults are a vast group. The state won’t hazard a guess at the number.

Under the legislation, the federal government would help states pay to cover them, but the states would have to chip in.

In Nevada, the money would come from the state’s sagging general fund.

One Washington estimate is that Nevada’s current $800 million Medicaid bill would grow by 5 percent, about $40 million annually.

Gibbons complains the feds are attempting to saddle the state with an unfunded mandate at a time when the tourism economy is in the tank and the state’s finances are in crisis.

Reid barked back that he is working to boost the federal share to Nevada — something he succeeded in doing this year and will likely be able to accomplish again.

Regardless, the state would have to pay more than it is currently. Hence the question: How much is too much for Nevada to pay to help cover its uninsured?

Nevada is a libertarian leaning state and has long avoided giving government a sizable role in health care. The result of that lack of government investment is that Nevada dwells at the bottom of national rankings on health care.

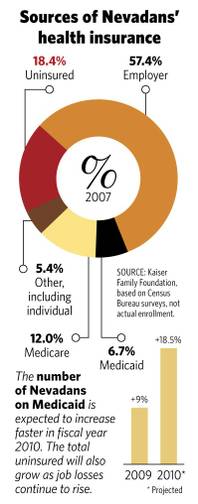

The state is in the top 10 for uninsured, with nearly one in five residents going without coverage — just eight states fare worse, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s statehealthfacts.org.

Nevada is ranked at the bottom for public assistance, sharing the cellar with four other states where just 11 percent of the population is enrolled in Medicaid, according to enrollment reports from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

While other states have over the years pushed to expand Medicaid coverage by digging into state coffers to supplement federal contributions, “We’ve not, as a state, decided to do that,” said Charles Duarte, the state’s Medicaid administrator.

•••

Now, Medicaid expansion is at the center of the health care debate in Washington, where reform advocates see it as the simplest way to increase the number of people with coverage.

Both the House and Senate bills propose an expansion of Medicaid to cover those on the lower-end of the income scale as part of the new requirement that every American carry health insurance.

States have historically had great leeway to decide who is eligible for Medicaid as long as they cover the basics — children, pregnant women, parents, seniors, the disabled.

Nevada essentially offers the minimum program required — coverage for kids from poor households (income of no more than $24,300 for a family of three, and slightly less if the children are older), pregnant women (income below about $20,000), parents (income of no more than $16,600 for a family of three) and low-income seniors and the disabled.

Both the House and Senate bills would require states to loosen the income requirement, allowing those who make a few dollars more to qualify. The bills would also require states to cover that new swath of residents — low-income, childless non-senior adults.

Duarte won’t estimate how many childless adults earning less than $14,400 annually exist in Nevada — but he knows it’s a large number. High-rollers skew Nevada’s average income upward, but there are countless shift workers at casinos and mom-and-pop stores who are not covered by generous union health plans or company insurance policies and are not making much money.

Estimates put the number of uninsured childless adults under 65 in Nevada at 250,200, according to statehealthfacts.org. And 198,400 non-senior adults are classified as low-income.

Plus, Duarte worries about the “woodwork effect” — the estimated 70,000 Nevadans who are eligible for Medicaid but have not signed up and might come out of the woodwork once they are faced with the new requirement that all Americans have insurance.

The state saw a 9 percent jump in Medicaid recipients in fiscal 2009, which ended June 30, and because of the recession expects an 18.5 percent increase in fiscal 2010. That’s a lot of poor people needing health care.

“Huge,” Duarte said.

For the governor, nothing short of full federal payment would work.

“We can’t even afford our current coverage, much less an additional expansion of coverage,” said Stacey Woodbury, the governor’s deputy chief of staff. “We don’t have any money.”

Even if the federal government paid 100 percent of the costs, the state would still be wary, she said. “Will they pay it forever?”

But others see in that approach more of the same for a state that has historically lagged in caring for the poor and is suffering the consequences of that underinvestment — burdened emergency rooms and unpaid bills.

“Nevada’s Medicaid has always been one of the lowest funded in the country,” said Democratic Rep. Dina Titus, the former state Senate leader. If Reid can fix the formula to get Nevada a greater share, she said, “It’s worth looking at.”

•••

The House and Senate bills take a slightly different approach to funding a Medicaid expansion.

Currently, the federal government splits the Medicaid cost with Nevada 50-50. Some states with lower incomes get more federal help.

Under the House bill, the federal government would provide 100 percent — the full cost of covering the new category of childless adults — for the first two years. Then the federal share would drop to 90 percent by 2015.

That means the state would eventually have to pony up a dime for every new $1 spent.

Under the Senate bill, the federal government helps states with the toughest climb, those such as Nevada that are not currently offering much Medicaid. The feds would initially provide 87.3 percent when the law goes into effect in 2014, dropping down to 82.3 percent by 2019.

The bottom line: Under the Senate plan, the state would pay 13 cents to get $1 in expanded care now, and 18 cents on the dollar into perpetuity.

That’s a tall order for a state staring down a $2.4 billion deficit.

Duarte notes that the extra federal funding applies only to those newly covered by the program, low-income childless adults. For the woodwork-effect people, who could have been covered in the past but are only now joining Medicaid, the state would still be reimbursed at the 50-50 rate.

Assemblywoman Sheila Leslie, D-Reno, an early supporter of President Barack Obama and one of the state’s most liberal legislators, understands the state’s dilemma.

“One of the best ways to attack the high percentage of uninsured is to increase the number of eligible participants on Medicaid,” Leslie said. “But even if the state has to pay 10 percent of the cost, it’s going to be very difficult. We have no money.”

•••

A chart floating around Washington last week showed that under the health care legislation being debated in Congress, Nevada would have to increase its spending on Medicaid by 5 percent — the second highest increase in the nation. The average was 0.89 percent.

Reid called the increase for Nevada unacceptable and vowed not to bring a bill to the Senate floor unless the state got a better deal. “During this time of economic crisis, our state cannot afford to shoulder the second highest increase in Medicaid funding,” Reid said in a statement last week after the bill was introduced.

“I spoke to the chair of the Finance Committee and he assured me that this bill will be improved for Nevada before he takes it to the committee,” Reid said. “Let me be very clear, I will not bring a health insurance reform bill to the Senate floor that is not good for Nevada.”

Reid’s ability to address the problem is not overstated.

He made sure Nevada received the largest increase in Medicaid funding in the economic recovery act by changing the formula to consider states with high unemployment rates. Nevada’s jobless rate, 13.2 percent at last count, is among the highest in the nation.

The result was one of the unsung victories for Nevada in the recovery act. The state’s usual 50 percent match from the feds was temporarily boosted to 63.9 percent, bringing in an additional $125 million so far this year.

The Senate Finance Committee chairman, Sen. Max Baucus of Montana, confirmed to the Sun that various “senators have requests on Medicaid payments and we’re working with them.”

But even Reid’s clout is not likely to get Nevada a 100 percent match. Both House and Senate bills require states to chip in something. A nickel, a dime, maybe 18 cents on the dollar.

So the question now is: How much would Nevada be willing to pay to reduce the ranks of its uninsured?

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy