Sunday, Jan. 25, 2009 | 2 a.m.

BY THE NUMBERS: COLLECTIONS

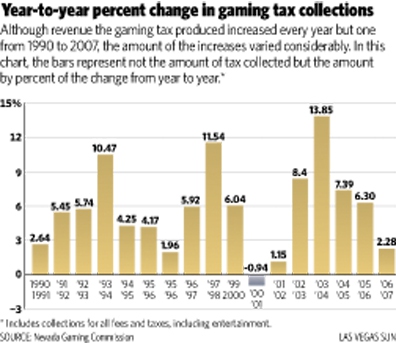

How hard did Nevada get hit by the drop in tax revenue from gaming? It’s hard to tell exactly because just the first three quarters of 2008’s total collections have been reported. Using figures for those quarters, here’s how collections from 2007 and 2008 compare.

$782,895,430 — In 2007, revenue increases slow: From 2004 to 2006, collections from gaming in each year increased by 8 percent to 9 percent. Collections increased by 2 percent in 2007.

$718,447,028 — And then the drop: Collections were down by 8.23 percent for the first three quarters of 2008.

* Includes collections for all fees and taxes, including entertainment.

Sun Archives

- UNLV economist foresees darker times (1-23-2009)

- Businesses brace for legislative session (1-23-2009)

- Legislators must look outside gaming industry for budget solutions (1-22-2009)

- Annual report shows dramatic fall of casino profits (1-16-2009)

- Group proposes new taxes to fix state budget (1-12-2009)

When Nevada legalized gaming in 1931, it was almost an afterthought.

The modest levies on card games and slots would be the garnish. The main course through tough economic times, state leaders believed, would be looser divorce laws adopted during the same legislative session to lure unhappy spouses to spend time — and money — in Nevada.

The gaming bill’s author, freshman legislator Phil Tobin, couldn’t know that 78 years later the quality of Nevada’s schools, public safety and services to the poor would depend on how much tourists drop in the slot machines and bet at the tables.

Over the decades, as the gaming industry grew and along with it gaming tax revenue, attempts to tax other businesses or the people themselves usually went nowhere.

Some warned against becoming overly reliant on a single industry to fund government. But almost by default, gaming became Nevada’s meal ticket, though not necessarily a generous one.

Gaming directly provides a third of state revenue. Add in sales tax paid by tourists and other levies related to casinos, and the industry accounts for half of all state money, according to some estimates.

Once thought to be at least resistant to economic recessions, gaming has staggered in this one. The warnings of an overreliance on gaming now seem prescient.

Revenue has fallen. Thousands of casino employees have been laid off. Massive projects that promised to bring greater prosperity to the state have been mothballed.

Statewide gambling revenue declined by 8.23 percent for the first three quarters of 2008 compared with a year earlier.

As the Legislature prepares to convene on Feb. 2, Democrats, who control the Assembly and Senate, and many Republicans are hinting tax increases might be needed to avoid the most drastic cuts proposed in Gov. Jim Gibbons’ budget.

For the first time in perhaps 50 years, however, almost no one is talking about raising the gaming tax. Even the industry’s biggest critics — among them groups that have always said the industry doesn’t pay all it should — have backed off suggestions that the state should look at increasing the gaming tax.

State leaders will likely have to find their way without the gaming industry.

•••

The gaming industry’s unlikely founding father never owned a casino, didn’t gamble and died having never seen the Las Vegas Strip.

Tobin, a quiet cowboy who had run for the Assembly to solve irrigation problems for ranchers in Humboldt County, couldn’t have foreseen that legalized gaming would become Nevada’s economic engine and largest source of tax revenue.

In a story published in 1964, he told Las Vegas Sun Carson City Bureau Chief Cy Ryan that he had two reasons for proposing gambling’s legalization.

“First, illegal gambling was prevalent. Everyone had a blanket and a deck of cards or dice and it was getting out of hand. Some of those tinhorn cops were collecting 50 bucks a month for allowing it.

“Secondly, the state needed revenue. This way we could pick up the money from the license fee for the games.”

Those fees were modest: card games were taxed at $25 per table, per month ($337 in today’s dollars) and slot machines were charged $10 per month for “each handle.”

The state, counties and cities shared the revenue.

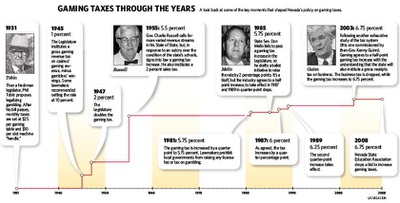

In 1945, the Legislature changed the way it taxed casinos, forever linking Nevada’s financial stability with the prosperity of its gaming industry. The state began taxing gross gaming revenue — the casinos’ gaming revenue, minus gamblers’ winnings.

“There was never some type of bargain struck” that legalized gaming would fund state government, said David G. Schwartz, director of the Center for Gaming Research at UNLV. “As gaming developed, it assumed the tax burden. No other industry did. But gaming could keep its taxes low compared to other states with gaming.”

In the debate that preceded the passage of the gross gaming tax in 1945, some argued the levy should be as high as 10 percent. Lawmakers eventually set it at 1 percent. (Two years later it was increased to 2 percent.)

Still, the industry protested. “The gamblers themselves ... claimed the new tax law would put them out of business and serve as a bar to the construction of new and elaborate hotels which they said were planned in the state,” the Reno Evening Gazette reported after the 1945 session.

Similar arguments would be repeated over the next 50 years, each time lawmakers entertained a proposal to raise the gaming tax. Despite the repeated forecasts that a higher gaming tax would be the death of the industry, gambling and the state boomed.

•••

The gaming tax embodied and perpetuated a quintessential Nevada philosophy — fund government by taxing the other guy.

The gambling levy wasn’t the only manifestation of Nevada’s anti-tax ethos.

Around the time gambling became legal, the state launched a campaign to lure wealthy individuals from across the country, promising them a safe harbor from taxes if they became residents. “The One Sound State” campaign, detailed in a 1937 Time magazine article, promised the well-heeled: “A balanced budget. No corporation tax. No income tax. No inheritance tax. No tax on gifts. No tax on intangibles. The greatest per capita wealth ($5,985).”

The magazine noted the state’s uniquely western philosophy, describing it as a place “where easy divorce, open prostitution, licensed gambling and legalized cockfighting are only the more luridly publicized manifestations of a free & easy, individualist spirit deriving straight from the mining camp and cattle ranch.”

During the session the Legislature legalized gaming, it also reduced the waiting period for a divorce to six weeks from three months. It was an attempt to increase Nevada’s share of the nation’s divorce tourism market.

The divorce trade was supposed to save us, said Bill Thompson, a UNLV professor who has studied gaming. Legalized gaming was “almost an afterthought,” he said.

The Legislature also debated instituting a lottery and eliminating all other taxes. (A lottery has remained a popular proposal to address the state’s funding problems. Bills to put a lottery before voters have been introduced in almost every legislative session since 1975.)

•••

In 1955, the state was at a crossroads, according to Collier’s Magazine, which published a scathing cover story on “The Sorry State of Nevada.” It had nation-leading suicide and crime rates, lacked a mental health clinic and was the only state that didn’t accept federal money for poor children in widowed or broken families.

“Too rich to accept normal taxes, too poor to maintain its institutions and agencies on a decent twentieth-century level, coddling known racketeers and making them respectable by legalizing their operations, while turning a cold, poormaster’s eye to its poor, its sick, its socially misshapen.”

Later that year, Charlie Russell, a Republican, won the governor’s seat on a no-new-taxes platform. However, in his State of the State address, Russell called for new sources of revenue.

Post-World War II Baby Boomers were entering schools and parents were horrified at what they found. Schools were underfunded and crowded; teachers were underpaid.

“For too long, Nevada has not met the responsibility of a planned program for the schools,” Russell said. “Every two years the problem has been met only with stopgap measures.”

Two years earlier, the Legislature had attempted to address the problem by increasing the kindergarten age, thus keeping enrollment down. But parents continued to protest. Hundreds showed up at PTA meetings, and they organized.

The “little mothers,” as they came to be known, lobbied legislators and generally raised a ruckus.

“You couldn’t turn a corner without one of the ‘little mothers’ buttonholing lawmakers in the hallways of the Statehouse,” Mary Ellen Glass, a little mother, wrote in the book “Nevada’s Turbulent 50s.”

Although some historians think Glass overstated the effect of the “little mothers,” it’s clear there was public pressure to better fund schools. Las Vegas’ superintendent of schools told newspapers that unless funding was increased, there would be a ballot initiative to raise taxes.

“Inevitably (gaming companies) would declare that they were carrying more than their fair share of the tax burden already, and thus the citizenry should prepare to pick up their own part,” Glass wrote.

In the face of gaming industry opposition, Russell signed a bill that more than doubled the state’s gaming tax to 5 1/2 percent. That session, Russell also signed into law the state’s first sales tax, which was 2 percent.

There was an uproar, particularly over the sales tax. Opponents put a referendum to strike it down on the ballot the following year. It failed by a 2-1 margin.

•••

The bill signed by Russell would be the last large increase in the gaming tax.

Despite polls showing voters overwhelmingly in favor of raising it, the political will was rarely there. When it was raised, the increase was incremental.

In 1959, a state study recommended the gaming tax be raised to 7 percent and that taxes on alcohol and cigarettes be increased. Nevada shouldn’t rely on a sales tax because it placed an undue burden on the poor, the report concluded.

But the prospering gaming industry had gained the necessary influence with state political leaders, who balked at raising the tax.

“We could kill the golden goose,” Assemblyman Thomas Kean, R-Washoe, said of the proposed gaming tax increase.

The gaming tax proposal died, while the levies on alcohol and cigarettes passed.

The gaming tax would remain unchanged until 1981, when the Legislature increased it by a quarter point, along with enacting a prohibition on local governments raising any license fee or tax on gambling.

That year the state enacted what would become known as the “tax shift,” moving sales tax money from local governments to the state and giving them property tax revenue in return.

With sales tax disproportionately paid by tourists, the state, in effect, became even more dependent on gaming.

The industry’s growing power was evident to state Sen. Don Mello, who took up a populist call to raise the gaming tax during the 1985 Legislature. “When you’re talking about raising the gaming tax, people tend to walk on the other side of the hall when they see you,” Mello said in an interview last year.

After failing to get the increase through the Legislature, Mello drafted a ballot initiative to increase the gaming tax by 2 percentage points. With the threat of the petition, the gaming industry agreed to an increase of a half point, a quarter point each in 1987 and 1989.

“It was probably 100 percent a bluff,” Mello said of his petition. “The teachers wouldn’t help me; the senior citizens wouldn’t help. No one. When you look at the fact that no one is coming to you, even if you’ve earmarked money for them, then that’s pretty bad.”

Bill Bible, of the Nevada Resort Association, attributes the gaming tax rate’s stubborn inching upward to an overall aversion to taxes in the state.

The state did continue to increase the sales tax as politicians repeatedly noted that it was paid disproportionately by tourists.

In the 1980s, amid a growing anti-tax movement nationally, groups in Nevada began pushing for a constitutional ban on personal and corporate income taxes.

The gaming industry feared that, with those options ruled out, the Legislature would go after gaming whenever the state needed new revenue. Making a political calculation, the industry funded a constitutional amendment of its own to ban a personal income tax, but not a corporate income tax.

The gaming-sponsored ballot measure won.

Despite gaming’s political muscle, it has failed to spread the tax burden to other businesses in Nevada, where native sons and daughters are still raised on the anti-tax philosophy of the past.

In 2003, following yet another exhaustive study of the tax system, this one commissioned by then-Gov. Kenny Guinn, an effort was made to introduce a gross receipts tax on businesses. As part of that proposal, gaming companies agreed to an increase in the gaming tax rate.

The business tax fell apart and the compromise — a patchwork of tax hikes that, combined, was the largest tax increase in state history — included a half point increase in the gaming tax.

Gaming industry leaders still grumble that they were again left holding the bag, while the state’s chambers of commerce walked away virtually unscathed.

•••

In the 1940s and ’50s, newspapers often editorialized that a reliance on gaming would give the industry too much influence over public policy. “The people who pay the piper will call the tunes,” one stated.

In later decades, concerns shifted to the potential economic perils of relying on a single industry to largely fund the state.

A study commissioned by the Legislature and completed in 1989 warned that Nevada would need to diversify its tax base to maintain services. A 1996 study concluded the state’s growth “will increasingly pressure Nevadans to look for government revenue sources other than gaming if current levels of government services are to be maintained.”

It’s an issue that has been debated each time the state faced recessions and budget shortfalls — in 1983, 1991 and 2003. And it will be debated again this year.

But the belief during tough times that gaming would come back always prevailed, said Guy Rocha, the state’s archivist. Las Vegas would build itself bigger and grander. And gaming taxes would continue to get us by.

“We had this unbounded optimism,” Rocha said. And it was always borne out.

This time might be different, Rocha said. “I’m of the opinion that it will come back. I don’t know if it will come back so big,” he said.

Not having gaming to shoulder most of the burden, Rocha said, will test Nevada’s “don’t tax me, tax the guy behind the tree” ethos.

“The growth of Las Vegas is not going to be the same anymore. I’m not saying it’s going to go away. I’m not saying people aren’t going to profit. But the revenue hand over fist, the geometrical expansion of gaming, I don’t think it will come back.”

And that may force political leaders to ask residents to, at last, pay for their own schools, roads and health care.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy