Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

Beyond the Sun

Nevada’s rate of infants born with syphilis is no longer the nation’s worst, according to a government report released Tuesday, but experts warn that the problem could worsen as low-income women face a shortage of prenatal care.

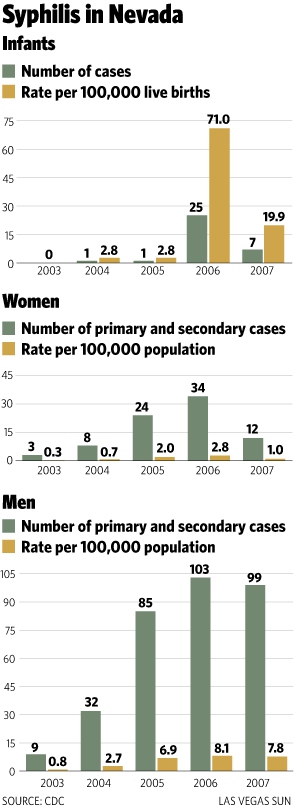

In its annual report on sexually transmitted diseases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that Nevada’s rate of congenital syphilis dropped to 19.9 cases per 100,000 live births in 2007, ranking seventh nationally.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease that had been nearly eliminated, has seen a resurgence in the United States since 2001 and a 15 percent increase between 2006 and 2007, the CDC reported. Syphilis, which is easily cured with penicillin, is spreading because sexually active people who aren’t tested are unaware they have it.

Rick Reich, communicable disease supervisor of the Southern Nevada Health District, said Las Vegas is in the midst of a “full blown outbreak” of syphilis. The number of reported cases in Las Vegas jumped from eight in 2003 to 102 in 2007. Part of the problem, he said, is that people don’t take the symptoms seriously because they don’t cause pain.

The CDC reported that gay and bisexual men made up 65 percent of syphilis cases in the country in 2007. The disease is primarily a threat to this population, which, health officials said, seems to be increasingly promiscuous and taking fewer protective measures because of a sense that HIV and AIDS are treatable.

Some of the men pass the disease to women, who can easily give it to their babies if it’s left untreated. Congenital syphilis, which can be easily prevented, is rare — there were 25 cases in the state in 2006 and seven in 2007 and can cause permanent problems for the newborn, including physical deformities, neurological dysfunction and mental retardation, with a resulting sharp increase in health care costs.

“It’s heart-wrenching,” Reich said of mothers who pass syphilis to their children. “It’s the easiest thing in the world to treat — two shots of penicillin and that’s it.”

The rate of congenital syphilis is also a sign of other public health problems, including women who are not getting appropriate prenatal care. The situation may worsen because University Medical Center, the county’s only public hospital, recently eliminated its prenatal services because of the state budget crisis. UMC’s prenatal program was one of the few options for low-income patients in Southern Nevada.

Local health experts say shuttering UMC’s program could lead to an uptick in congenital syphilis cases. Dr. Carl Heard, chief medical officer for Nevada Health Centers, a nonprofit organization that runs low-income clinics, said there’s been a “significant increase” in women seeking services since UMC stopped accepting new patients. Clark County has one of the highest rates in the country of women who receive no prenatal care and just drop in to the emergency room to give birth.

In 2004, statistics show, 9.6 percent of women giving birth in Clark County received no prenatal care until their third trimester or none at all, compared with 3.6 percent nationally.

“In the end we don’t really have a state that invests in the needs of its underserved population, and that’s why we have such poor public health measures,” Heard said. The state’s rate of pediatric syphilis is sure to rise as future budget cuts reduce the available prenatal care, Heard said.

As for Nevada’s rank in cases of congenital syphilis: “We can count on being number one later,” Heard said.

UMC officials said they do not think eliminating their prenatal services will have any negative effect on the ability of women to get prenatal services in Las Vegas. Through the hospital’s Family Resource Center, pregnant women are referred to other providers for care, UMC officials contended, so there will not be a reduction in service to the community.

But in fact, other doctors may not take patients who don’t have the ability to pay.

Heard, one of the providers that now takes UMC patients, said he’s sensitive to the challenges that led UMC to cut its prenatal care, but that the cuts do reduce the ability to get prenatal care.

“You take a safety network player and pull them out, and there has to be a reduction in services or else they weren’t providing any services in the first place,” Heard said.

Reich, of the Southern Nevada Health District, said the outcome when prenatal programs are cut is that fewer women will get the care they need. He urges them to, at a minimum, get tested for syphilis.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy