Sunday, Aug. 2, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- City quietly ends arena talks with REI Neon (10-15-2008)

- city holds out hope for arena downtown (8-21-2008)

- Told you, critics of arena play say (8-2-2008)

- Casino plan may survive arena's death (5-30-2008)

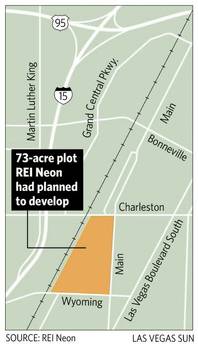

From the beginning, city officials acknowledged the $10.5-billion dreams of REI Neon — a basketball arena, casino and boutique hotel on 73 gritty downtown acres — were a long shot.

Mayor Oscar Goodman, whose enthusiasm for efforts to redevelop his downtown is legendary, acknowledged at the time that it would be a “miracle” if the Bloomfield Hills, Mich., company pulled off its plan for the site south of Charleston Boulevard.

Critics voiced similar doubts, even suggesting the proposal was a ruse.

Chuck Gardner, the attorney for concerned residents who live near the site, claimed the developers — including local real estate firm TR Las Vegas, which worked with REI Neon to assemble the land — simply wanted to “flip,” or sell at a higher price, the property with gaming rights attached.

Although the City Council formally ended REI Neon’s quest to build an arena in October, the future of the “gaming overlay district,” which would allow casinos on the site, is unclear.

At his most recent weekly news conference, the mayor said city officials had told him the gaming district remains intact, even though REI Neon’s project is dead. Goodman added that although the project was the reason the City Council approved the gaming district, he would “love to see more casinos in that area.”

Critics of the plan, however, have sued, arguing the gaming district shouldn’t outlive the project.

The future of the gaming district could be decided when District Court Judge Linda Bell hears a lawsuit over the matter on Aug. 11.

• • •

REI Neon’s plan was doomed practically from the moment of its approval, two years ago.

A few businesses within the site — south of Charleston Boulevard and north of Wyoming Avenue, east of the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and west of Main Street — never agreed to sell their land.

Outraged neighbors filed suit to stop the project. Some were concerned that a huge basketball arena and casino could radically alter the aesthetic of the arts district and possibly wipe it out through jacked-up rents that would force out modest arts-related businesses.

Perhaps most significantly, credit markets collapsed just weeks after REI Neon’s deal with eager city leaders was inked.

Financing was a serious question even when credit was more readily available.

To put REI Neon’s $10.5 billion price tag into perspective, CityCenter is currently estimated to cost $8.4 billion. And the REI Neon project was slated to be built downtown amidst auto repair bays, cheap furniture and fast-food stores and precious little foot traffic — a universe away from the CityCenter’s middle-of-the-Strip location.

At a June 2007 council meeting, an REI Neon official promised the developers would be able to tap the deep financial pockets of “multiple billionaires.” At one point, Goodman asked REI Neon official Greg Borgel to confirm that four billionaires “who have contacts with the business community” were lined up to be principal investors.

“I’m not asking for their names,” Goodman said, according to a transcript of the meeting.

“Oh good, ’cause I can’t tell you,” Borgel replied. Borgel later added that several of these rich investors “are the kinds of billionaires that own portions of NBA teams.”

As of that meeting, REI Neon investors had spent more than $20 million in “hard and soft costs.”

According to REI Neon President Jon Weaver, the project’s failure was the result of a severely soured economy and dried-up credit markets — something that couldn’t have been predicted when the deal with the city was cut.

In one regard the timing of the deal’s failure might be beneficial, Weaver said, considering construction never began. The site isn’t home to the stilled cranes and half-built structures that dot the Strip, he said.

“From a community standpoint, I think there’s a benefit that the project never started,” Weaver said.

REI Neon has left the state and let its business registration with the secretary of state lapse in January.

• • •

The two lawsuits involving the site are a complaint by Gardner’s clients and a suit by the Culinary Union, whose offices are near the downtown site.

The suits, which have been consolidated, claim that the city had no right to approve REI Neon’s land use applications — including the gaming rights — because the developer didn’t own the land. TR Las Vegas had gained preliminary approval from most of the property owners in the area to sell their parcels provided the project was financed and built.

Paul Larsen, a lawyer for REI Neon, agreed with the position of Gardner and the Culinary. Larsen wrote on July 9 that REI Neon “concurs … that the gaming enterprise district (and underlying land use entitlements) under review in this case expired on June 20, 2009, and no extension of time was sought before the City of Las Vegas.”

Robert Reel, a principal with TR Las Vegas, did not return calls for comment. But during a July 14 hearing in the case, he said his group had asked for an extension for the eight land use applications in the case.

But according to a transcript of the hearing before District Judge Tim Williams, an assistant city attorney said TR Las Vegas’ extension applications had been rejected. On July 19 Judge Williams found that each of the city’s land use applications for the REI Neon site had expired.

On its Web site, TR Las Vegas claims it continues to hold the right to sell parcels within the REI Neon site.

“The site had achieved zoning for a mixed use development including gaming, retail, condo, hotel and a 22,000 seat events arena,” the company states. The project “may be acquired in its entirety or in portions with financing options available.”

In other words, TR Las Vegas continues to contend — with Goodman’s apparent backing — that the site could and should be sold again to developers for a big casino project.

That’s a misrepresentation of the situation, Gardner says.

First, there’s no longer one gaming enterprise district, there are four, because the city never vacated the streets and alleys within the 73-acre site that separate them, Gardner says. But it doesn’t matter how many gaming districts might still technically exist, because none legally should now that REI Neon’s plan is dead in the water.

Gardner said he hopes to persuade Judge Bell to order the City Council to make it clear that any gaming district on that site no longer exists.

Said Gardner: “We just want to make sure the city makes it clear — and makes it go away.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy