Construction continues Monday at MGM Mirage’s $9.2 billion CityCenter project, where six workers have suffered fatal injuries in the past year and a half. Recent studies gauged workers’ perceptions about safety at the site.

Tuesday, Nov. 18, 2008 | 2 a.m.

The Reports

The Center for Construction Research and Training was created by the National Building and Construction Trades department of the AFL-CIO to conduct research and training in construction safety and health. Its research initiatives are funded by the federal government.

The Site Visit Report for CityCenter and Cosmopolitan was conducted by Janie Gittleman, Center for Construction Research and Training associate director of safety and health research; Don Ellenberger, director of the Hazardous Waste Training Program for the center; Pete Stafford, executive director of the center; Matt Gillen, coordinator of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health construction program; and Max Kiefer of NIOSH.

The worker survey for CityCenter and Cosmopolitan was completed by Gittleman, Stafford, Elizabeth Haile, Peter Chen, professor of industrial-occupational psychology at the Colorado State University, Paige Gardner, and Konstantin Petkov Cigularov, assistant professor of industrial-organizational psychology at Illinois Institute of Technology.

Enlargeable graphic

Workers Express Concerns Over Safety

Open-ended questions at the bottom of a survey taken by nearly 2,000 workers at CityCenter and Cosmopolitan provoked a range of concerns. Among them:

On housekeeping

- Portable toilets are not emptied often enough.

- Water isn’t replenished frequently enough.

- Not enough trash receptacles. Trades don’t clean up after themselves before the next one comes in.

On communication

- Concern about job loss if trade-offs are made to favor safety over production.

- Better scheduling is necessary so that each trade has the time to complete its work without interference from other trades.

- Remediation of problems identified by workers isn’t done in a timely fashion.

- Safety people preach safety, but in their absence general foremen and superintendents start yelling for production. They care more about their bonuses than for the people who work for them.

- The only time safety is a priority is when OSHA visits the site.

- If safety concerns are reported, workers get punished for holding up progress, or laid off. “I used to be a good person and not look the other way, but now I must or I won’t have a job.”

On safety and injury hazards

- Holes in floor often are not covered and properly marked.

- Small debris, wood, nails and metal clippings falling from higher floors.

- There aren’t enough safety people.

- Perini seems satisfied with the illusion of safety: A Perini safety person walked up a damaged ladder, stepped over a hole and sent a guy home for not wearing safety glasses. The next day the ladder was still damaged and the hole was not covered.

On health hazards

- Insufficient ventilation.

- Complaints about exhaust, fumes and dust are unaddressed.

- Workers get sick from the heat.

Sun Topics

For the past year, Perini Building Co. has said repeatedly it is doing everything it can to create safe work sites at CityCenter and Cosmopolitan, the giant Strip construction projects where the deaths of eight workers in a year and a half have sparked widespread concern.

Now, two stinging reports say there’s more the general contractor can and should do.

Perini sends mixed messages about the importance of safety to workers, avoids finding the root causes of accidents and instead places full blame on workers, and is perceived by some workers as placing scheduling concerns ahead of safety, according to the studies, issued by the Center for Construction Research and Training with assistance from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

The reports from worker surveys and visits conducted in August paint a picture of a site dangerously congested with workers who fear falling debris, feel pressured by supervisors to ignore safety in the rush to finish a job, suffer from heat and exhaustion and don’t always have access to drinking water, get in arguments with workers of other trades because of scheduling conflicts, and often don’t wear basic personal protective gear — particularly safety glasses.

“Noncompliance with basic (personal protective equipment) requirements is indicative of a poor safety culture, an ineffective safety program, and lack of supervisor/foreman understanding of their responsibility for safety,” researchers wrote.

Safety concerns at the massive Strip construction sites were amplified after six workers died at MGM Mirage’s $9.2 billion CityCenter project and two died at the adjacent $3.5 billion Cosmopolitan between February 2007 and June 2008. Both projects are overseen by Perini. Together they are without peer among private commercial projects in their level of complexity, cost, speed and number of workers in proximity.

The research was the result of an agreement reached between the Southern Nevada Building Trades Council and Perini after a one-day worker walkout over safety in June. That job action followed a Sun investigation that found a pattern of safety oversight problems at Strip construction sites, based on a review of accident reports from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and interviews with safety experts, union officials and workers. They complained to the Sun about the rush to get the massive project completed, leading to site congestion, worker fatigue and other factors that undermine safety.

Perini allowed the safety researchers to walk the site, talk to workers and managers and conduct a limited review of documents in August.

The researchers saw for themselves safety issues at the site, watching as a crane operator left his cab, stepped onto an external ledge of an unguarded platform with no fall protection or hard hat and grabbed a tag line to assist an ironworker and glazier hang a corner piece of curtain wall on the 54th floor of the Aria building. A Perini safety staff member told the crane operator to get back in his cab. But the observers, all construction safety experts, were disturbed that Perini didn’t appear to have a policy to warn others against making the same mistake, or a practice to better understand the worker’s motivation.

That extra step of finding and acknowledging root causes of safety breakdowns seemed to the researchers a missing link in safety practices at CityCenter and Cosmopolitan.

Understanding how safety problems arise out of efficient construction “can lead to ‘teachable moments’ for the individuals involved and valuable insights for safety program management,” the report states.

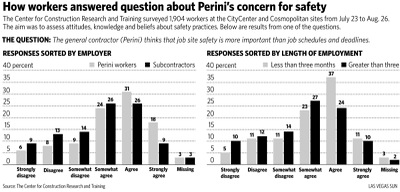

Similar patterns were found in preliminary results of a safety-climate survey, designed by the researchers, of 1,904 workers who attended a safety training class in July and August.

In addition to those two reports, both obtained by the Sun, the center has also provided Perini with an audit of fall hazards conducted by researchers from West Virginia University. The research will culminate in a final safety climate survey report to be issued in December.

Representatives of both Perini and the Southern Nevada Building and Construction Trades Council declined to comment until they had more time to review the reports. Center for Construction Research and Training Executive Director Pete Stafford said he won’t comment until the center has heard back from Perini, which he expects to happen next week.

Perini has maintained in past interviews and statements that individual worker mistakes caused fatalities and injuries and said there is no pattern of problems. It has ramped up a series of marketing campaigns to educate workers about the importance of following safety rules. The company maintains “zero tolerance” for safety violations and fires workers who do not follow safety rules, executives say.

But in laying out a series of examples and recommendations, the new reports caution the company not to rely on that approach alone.

“It appeared that the safety program philosophy emphasized enforcement and discipline for workers who did not follow rules and policies (as opposed to holding supervisors and contractor management responsible),” the report states.

Researchers emphasized points where management could do a better job of taking responsibility for safety. For example, they found through safety-meeting minutes that 47 percent of the safety personnel who were supposed to attend a particular safety meeting did not show up, apparently without consequences. The patterns of problems raised at safety meetings did not always appear to be reviewed and addressed by management, the report states.

Researchers also observed safety personnel tell workers to fix safety problems such as leaking oil or electrical cord trip hazards, instead of involving management and supervisors.

“This is not conducive to a successful safety program,” they wrote.

Also of concern, researchers found that the company’s accident investigations are conducted by the foremen who oversees the crew involved in the incident rather than a more impartial person who could investigate whether the foreman’s conduct had contributed to the accident.

Perini’s accident investigation reports also omit many possible key root causes of accidents including bad supervision, design issues, schedule and production pressure, training problems, factors caused by multiple contractors sharing the same workspace, fatigue, inadequate maintenance or inspection, faulty procedures, language problems, or coordination issues.

The researchers warned against the “natural tendency” to blame errors and accidents on individual workers without looking into “latent conditions such as time pressure, understaffing, inadequate equipment, fatigue, inexperience, unworkable procedures, or unanticipated conditions.”

Perini was faulted for not following up with subcontractors after accidents or tracking accidents across the job site to learn whether certain contractors on the site have suffered a particularly problematic pattern of injuries.

The researchers who attended a daylong safety orientation for new hires said the workers were given indirect messages that undermine safety. For example, Perini told workers to report safety problems when they see them, but didn’t explain how or to whom, according to the report.

They noted that a Spanish translator stopped translating just 15 minutes into the orientation, even though about 30 percent of the workforce doesn’t speak English.

Nor was there mention at the orientation about fatalities at the site.

“Not discussing the previous site fatalities contradicts messages about commitment, openness, and the importance of communicating about safety and health problems,” the report states.

Researchers recommended that Perini not only tell new hires about the fatalities, but also circulate detailed information about accidents among workers so that they can dispel rumors and prevent reoccurrence of the same problems.

For some workers, the message that Perini places a priority on safety does not appear to be internalized.

In the survey of nearly 2,000 workers, more than one-third said they believe Perini considers job schedules and deadlines more important than safety and 59 percent said they can’t do their job safely because of other trades being in their way. Thirty-nine percent of workers believe Perini does not solicit safety feedback from workers, 30 percent believe the safety staff does not follow up on safety problems, and 23 percent report they sometimes ignore a hazard, work around it and don’t report it because of time pressure.

“I used to be a good person and not look the other way, but now I must or I won’t have a job,” one worker said in an open-ended question at the end of the survey.

Workers and supervisors told the researchers that work site congestion, coupled with scheduling problems, created tensions among the trades and more risk of injury from falling objects.

“Workers don’t care what happens to the other workers, because of the ill will that has developed,” one worker said.

The report stated, “One sheet metal worker said he’s been working in the trade for over 20 years, that this was the first job he’s been on where he really worried that he might get injured, due to what other trades were doing that he had no control over.”

A sheet metal foreman said that “scheduling and pressure from top management were responsible for the safety incidents that have occurred” and described an incident where someone on his crew could have been seriously injured by a piece of iron grating installed by ironworkers that fell onto the area where they work.

“He believes the pressure to get work done was responsible for the go-ahead to work below the ironworkers while they were installing the grating,” the report said.

On the other hand, some workers told researchers they observed the site is getting safer over time.

In June and July, OSHA conducted a comprehensive inspection of the site. Some workers said that Perini “was trying to do the right thing regarding safety” and “emphasized that before OSHA showed up the situation was a lot worse.”

Yet, on Aug. 14, the researchers said they observed a near-miss incident with a vehicle at an excavation project in which the swing radius of a backhoe extended beyond the controlled work zone and into areas of vehicular and pedestrian traffic.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy