Sunday, May 25, 2008 | 2 a.m.

The economic downturn is hitting low-income residents in Nevada faster and harder than in the rest of the country, according to a Las Vegas Sun analysis.

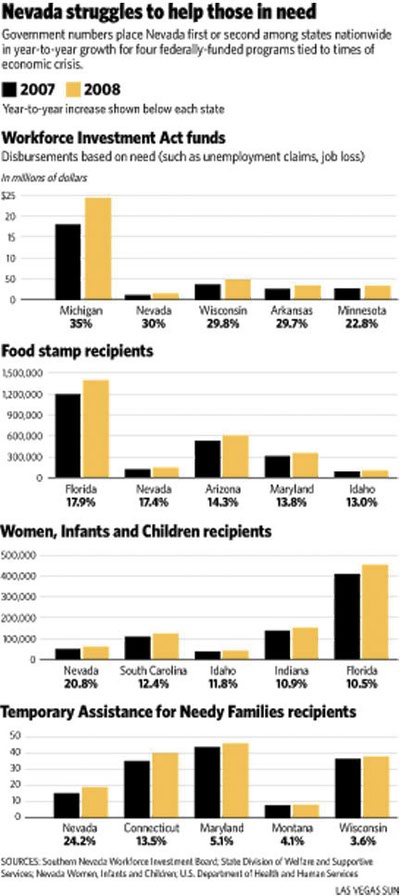

Tens of thousands of Las Vegas Valley residents are seeking a lifeline from government services, pushing up caseload numbers faster than in the rest of the nation at key federally-funded programs tied to times of economic crisis. Nevada is first or second among states nationwide in year-to-year growth in those programs.

The data are “jaw-dropping,” said John Ball, executive director of the Southern Nevada Workforce Investment Board, an agency that receives federal money to train people for jobs.

His program is one of the four looked at by the Sun. The other three are food stamps; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, which people more commonly refer to as welfare; and Women, Infants and Children, known as WIC, which supplies food and information to mothers.

During the past year, the number of people in Nevada’s welfare and WIC programs grew 24.2 percent and 20.8 percent, respectively — tops nationwide. And workforce funds, which are based on need, shot up 30 percent, while the number of people getting food stamps increased 17.4 percent. Those increases were second highest among all states.

“We’ve clearly got a pattern here,” Ball said.

Ball said the numbers are a reflection of an economy built on two increasingly unsteady pillars: homebuilding, hit hard as a trickle-down outcome of the foreclosure and mortgage crises, and tourism, affected by high gas prices and the overall economic downturn. As those pillars waver, people have lost jobs or taken pay cuts.

Nevada’s rankings also show how far we had to fall, says Jeremy Aguero, principal of Applied Analysis, a research firm.

“We’re a victim of our own success — the remarkable strength of the economy ... was simply unsustainable,” Aguero said. “Now it’s right-sizing.”

Blows to our local economy together with nationwide spikes in food and gas prices may be the reason for longer lines at welfare offices across the state.

Data from the four programs show that during rough times in the valley, “those that have the least to lose — the poor — lose the most,” according to Aguero, whose list of clients includes Clark County, Wynn Las Vegas and the Legislative Counsel Bureau, the state’s research arm.

Ball thinks the numbers could foretell growth in the gap between the haves and the have-nots in Nevada. “If communities aren’t careful, they can get into a scenario where there is a large divide between the successful and the unsuccessful.”

But all the analysis means nothing to those who, like Gina Larason, are adding the increased price of a gallon of milk to the price of a box of cereal and coming up short. Three months ago, Larason’s boyfriend lost his job as a computer technician. They couldn’t pay the rent so they lost their apartment. She and her daughters moved in with her relatives, and her boyfriend went to live with his family.

A recent hot afternoon found her pacing outside a state office on Flamingo Road, waiting for her number to be called.

Applying for food stamps at the office “seemed like the right thing to do,” she said with resignation.

A high-school dropout who later earned a GED, the 24-year-old mother has few job skills, but she has been looking for work just the same.

She has also applied for welfare to go along with the food stamps, a situation she hopes is temporary, because she never pictured herself depending on the government for help.

“It don’t feel good to be there,” she said, shaking her head and motioning to the busy waiting room behind the state agency’s doors. “I don’t want to get enabled.”

Tens of thousands of Las Vegas Valley residents are reaching similar conclusions. Nearly everyone outside the Welfare and Supportive Services Division office that afternoon was there for the first time, applying for food stamps and other benefits.

Aguero said many people who came to the valley during its chart-topping growth of the past decade-plus didn’t bring marketable skills or college degrees. Many left friends and family behind. And considering the dearth of privately run programs here, it’s clear why people would turn to government programs in times of need, he said.

Still, Stacy Dean, director of food assistance policy for the Washington, D.C.-based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said many families turn to such programs as a last resort, often letting pride or shame stop them from seeking help. Now, she said, “the bite of the economy coupled with rising prices has proved too much.”

Tony Urich stood outside the Flamingo Road office on a recent afternoon, having a smoke, pretty confident he would receive medical help for his epileptic 3-year-old daughter, but also hoping he would qualify for food stamps. The 38-year-old single father of four is among the growing number of Nevadans who seek help not because they’re out of work, but because their paychecks don’t stretch far enough.

Urich works about 40 hours a week in landscaping, earning $8 an hour. He said that doesn’t cut it, especially because “everything costs double now” and his children “like junk food like pizza.”

Urich’s situation reflects another change that may be driving up Nevada’s numbers, Dean said.

“The working poor historically haven’t been seen turning to these programs,” she said.

About three of four Nevada households receiving food stamps report some form of income, about twice the national average.

At one of the 14 WIC clinics in the valley recently, several mothers were in the same situation: working full-time but unable to make ends meet.

The program’s data reflect changes in food prices in Nevada. According to David Crockett, state WIC program manager, the average WIC participant spent $34.42 on milk, cereal, eggs, cheese and other foods allowed by the program in March 2008. During the same month a year ago, the same foods cost $30.24. That’s a 13.8 percent increase. Crockett thinks the cost will reach $37 by the end of summer.

Giselda Garcia, five months pregnant, stood in the parking lot behind the office. The 21-year-old had just applied to WIC for the first time. She works full-time at a King Ranch supermarket and earns $8 an hour. The program will help her learn about staying healthy during her pregnancy, as well as give her ATM-like cards for buying food.

Other mothers and couples leaving the WIC office had jobs but needed help paying their bills.

Of course, federally funded programs such as the workforce investment board, food stamps, welfare and WIC aren’t the only places where people seek that help.

Clark County Social Service, with a $175 million annual budget, is the other large source of benefits for the valley’s poor, providing everything from rental assistance of $400 a month to health care. Its director, Nancy McLane, said 35 percent more people came to the doors of her agency in April than in the same month a year ago.

“I’ve never seen a jump like this before,” said McLane, a 26-year county employee.

“People are making choices between buying gas and food,” she added.

McLane said her agency is closely monitoring the fiscal effects of increased need, noting that the agency’s budget comes from property taxes and seems to be in good shape — for now. Her main concern is customer service — she’s trying to find ways to have staff spend less time on the phone so they have more time to see clients in person. Her agency is also looking into seeking grants for the first time.

Officials at state agencies offering federally funded services are also asking themselves where to trim if demand continues to rise. Crockett said increasing numbers of participants and rising food prices have caused him to seek $400,000 from the federal government to get his agency through the fiscal year, which ends Sept. 30. If the bigger caseloads and higher costs aren’t met by increased funding next year, Crockett said, his agency might have to make waiting lists or limit eligibility — say, by, removing 4- and 5-year-olds from the program.

Nancy Ford, administrator for the state Welfare and Supportive Services Division, said the federal government will fund food stamps according to need. But the state pays for administering the program. Welfare funding, meanwhile, is finite. Ford said money for that program has not included any increase for population growth since 2001. Nor has it increased to match rising costs of living.

So her agency has been holding public hearings throughout the state this year to solicit the public’s opinion on the widest range of cost-saving measures in years, including several ways of limiting eligibility for food stamp and welfare programs.

Several analysts said the current numbers have meaning beyond the programs themselves. The increases may point to deepening poverty that may in turn lead to other social problems down the road, they said.

“We know that bad outcomes are related to economic deprivation, especially for children,” said Keith Schwer, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at UNLV. Those outcomes include falling test scores in school stemming from poor nutrition, he said.

“What comes right behind these numbers,” Ball said, “are increased numbers of people in jail and in the justice system and increased drug and alcohol problems and domestic violence, not to mention the stress placed on families.”

He sees the numbers as a wake-up call that says: Diversify the local economy and get serious about education.

McLane isn’t sure we should draw sweeping conclusions from the data just yet. She said some of the increase in demand for help may come from increased population, or from greater access to services.

Ford is less sanguine.

“Historically, we’ve been able to weather recessions,” she said. “There’s no end in sight this time.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy