Friday, May 16, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Beyond the Sun

By shuttering its kidney transplant program and shifting its patients to University Medical Center, Sunrise Hospital & Medical Center is shedding a fledgling program that consistently failed to meet expectations.

UMC, a cash-strapped county hospital seeking paying patients, now will become the only hospital in Nevada to perform kidney transplants. Accepting patients who otherwise might have gone to Sunrise will bolster UMC’s program, which should help its bottom line, justify new equipment purchases and help recruit doctors.

In giving their announcement the best possible spin, Sunrise officials emphasized this week that patients would benefit from consolidation of the two transplant programs. And this will likely be true.

Left unmentioned was Sunrise’s poor track record for kidney transplants. Its program has generally failed to meet the expected outcomes for such procedures, based on comparisons with other transplant centers nationally.

The two doctors who performed the procedures at Sunrise will join the UMC transplant team.

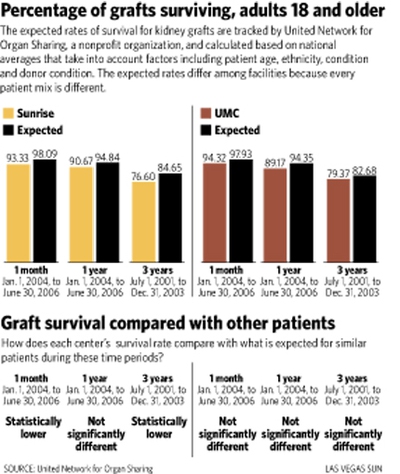

Every kidney transplant in the United States is tracked and regulated by the United Network for Organ Sharing, a nonprofit organization that reports the observed and expected survival rates for transplanted kidneys and patients who receive transplants. The expected rates of survival — for kidney grafts and patients — are calculated based on national averages that take into account factors including patient age, ethnicity, condition and donor condition.

The UMC numbers are within the expected range of performance compared with the averages from the nation’s 248 kidney transplant programs. But Sunrise’s kidney graft survival rates have been perennially lower.

According to the organ-sharing network, from July 1997 to June 1999 about 10 percent of Sunrise kidney grafts did not survive the first month — almost three times the expected failure rate — and 38 percent did not survive 34 months, about twice the expected failure rate.

From January 2001 to June 2006, the network found, almost 7 percent of kidney grafts did not survive the first month — more than three times the expected failure rate — and about 24 percent did not survive three years, about 1 1/2 times the expected failure rate. Both figures were found to be statistically significant.

Ashlee Seymour, spokeswoman for Sunrise, said the United Network for Organ Sharing had worked with the hospital to improve the program, making recommendations so it could improve its outcomes.

Still, Sunrise patients died at a higher-than-expected rate, though the numbers are not statistically significant, the network’s data show.

Dr. Scott Slavis, the surgeon who performs the operations at Sunrise, said the low performance numbers were attributable to older, sicker, higher-risk patients. It took many years for the organ-sharing network to provide Sunrise with data that showed its lower success rate compared with other programs, he said. Once it became clear that more patients were dying at Sunrise and that more kidneys were failing, doctors more aggressively screened applicants for a transplant, he said.

In the three years since, Sunrise’s performance has improved greatly, Slavis said. The network data are too dated to reflect the positive change, he said.

Slavis praised the UMC and Sunrise administrators for cooperating when they had been competitive in the past. He said it will certainly benefit the community.

“One program can focus on spending their financial resources and time to handle this properly rather than two places doing it part time,” Slavis said.

Sunrise Chief Executive Sylvia Young said she would not address the poor performance numbers specifically, but said that generally “the lower-volume programs struggle” because practitioners and staff are less experienced.

“The higher your volume, the better your outcomes are going to be,” Young said.

The Sunrise program struggled to expand because insurance companies will often not refer to programs unless they perform at least 50 transplants a year for three straight years, Young said. Since 1990 the program had 50 or more transplants only in 1999 and 2000, when it had 51 and 50, respectively, and the numbers dwindled to 25 in 2007, network data show.

The precipitous decline was hastened by the breakdown in late 2006 in the contract between insurance giant Sierra Health Services and HCA, the corporation that owns Sunrise, Young said.

Young, who has been in her position for about a year, said shifting Sunrise’s program to UMC will help the county hospital draw more than 50 patients a year and may help UMC recruit a multiorgan surgeon.

Sunrise will end its program July 1.

UMC spokesman Rick Plummer said UMC hopes to recruit a multiorgan transplant surgeon, and boasting a larger program will help draw the right person. Combining the two programs increases the collective knowledge, which will improve outcomes for patients, he said.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy