Thursday, May 15, 2008 | 3 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Test Site is once again making noise (4-30-2006)

- Personal stories bring Test Site history to life (12-7-2004)

- Blast from the Past: Nevada Test Site proves a powerful tourist hot spot (9-5-2002)

- Weatherman Gives 'Green Light' For Observer Project (4-22-1952)

- All Radio Networks to Cover Test (4-22-1952)

- Vegans Advised To Take Precautions Against Shock Wave (4-22-1952)

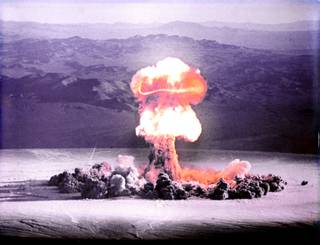

Predawn atomic fireballs and billowing mushroom clouds — plus the radioactive and political fallout accompanying them — are all part of Nevada's long-time association with nuclear weapons testing.

The government's nuclear testing, which was at one time capitalized on by Las Vegas businesses as a super fireworks spectacle for tourists, began six years after the first atomic bomb, Trinity, exploded on July 16, 1945, in New Mexico.

At that time, the government wanted a nuclear proving ground on the continent to save money after it conducted expensive atomic tests in the Pacific Ocean. It also wanted federal scientists to be able to continue their secret work far from the Korean War.

That lead to President Harry Truman approving on Dec. 18, 1950, the Nevada Test Site, which was 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas. The barren testing range carved out of the Mojave desert would be home for the next several decades to 928 of the 1,054 above- and below-ground nuclear experiments conducted by the U.S. The testing finally ended in September 1992 when a moratorium went into effect.

Over the years, up to 100,000 people have worked at the Test Site, with more than 12,000 employed there during the peak years of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The first nuclear experiment in Nevada lit up the desert sky on Jan. 27, 1951. In May 1953 the government triggered an above-ground nuclear blast code-named “Harry,” whose radioactive fallout blanketed not only the arid desert, but farm fields, homes, schools, factories and businesses across the country. The fallout even wiped out film at Kodak headquarters in Rochester, N.Y. Government agents washed cars and brushed (with whisk brooms) the clothes of residents of St. George, Utah. The government assured those residents everything was safe, but at least 4,390 sheep grazing in Utah died from radiation sickness. The government admitted nothing.

Since the beginning of the Test Site, protesters have demonstrated against the tests. Included in the numerous groups were homemakers who showed up in the 1950s, wearing shirtwaist dresses and carrying parasols. The largest protest occurred in the 1980s when more than 3,000 demonstrators made their feelings known. Famous protesters included scientist Carl Sagan, actor Martin Sheen and singer/songwriter/actor Kris Kristofferson.

Supporters of nuclear testing considered themselves “Cold Warriors,” fighting a major nuclear threat from the Soviet Union. Others, many of whom called themselves “downwinders” because the wind had placed them in the path of the radioactive fallout clouds, fought the secrecy and silence surrounding the U.S. nuclear testing program.

In 1984 a federal judge in Salt Lake City ruled the government had been negligent by exposing thousands of downwinders to radioactive fallout. Utah, Nevada and Arizona residents described the cancers and other radioactive illnesses they or their families suffered. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate 11,000 people died from diseases directly related to nuclear test fallout. Later, Test Site workers sued the government and lost their case.

The Test Site was the second largest employer in Nevada during its peak years, behind the mining industry, according to Energy Department records. The casino industry came in a distant third. Workers labored in secrecy at the remote site, which is larger than Rhode Island. Employees weren’t allowed to tell their families about nuclear activities witnessed there.

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev signed a treaty that required the superpowers to conduct nuclear experiments underground. The historic treaty banned nuclear testing in the air, oceans or space.

Kennedy has been the only sitting president who visited the Test Site. He toured it in 1962.

From 1980 to 1984 the Test Site became an outdoor laboratory for experimenting with a nuclear defense shield envisioned by President Ronald Reagan. Critics named the project “Star Wars.”

Today the Test Site offers a remote location for chemical tests and training for homeland security. In addition, researchers conduct subcritical experiments, testing radioactive components of nuclear weapons, but the explosions do not cause a nuclear chain reaction. By presidential order, the site must be ready to resume nuclear weapons tests within 18 months to three years after a presidential or congressional order.

It wasn’t until 1993 when President Bill Clinton and Energy Secretary Hazel O’Leary released more information to the public about how military personnel and citizens had been exposed to radioactive fallout. Still, many of the secrets of atomic testing in Nevada remain under lock and key.

Explore Las Vegas’ past and present

Explore Las Vegas’ past and present Boomtown: The Story Behind Sin City

Boomtown: The Story Behind Sin City Neon Boneyard: A 360° look

Neon Boneyard: A 360° look Mob Ties: See the connections

Mob Ties: See the connections Implosions: Classic casinos crumble

Implosions: Classic casinos crumble