Tuesday, July 22, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Audio Clip

- Jerry Tarkanian on spending summers in San Diego.

-

Audio Clip

- Tarkanian on Charlie Spoonhour and Lon Kruger embracing him when they coached UNLV.

-

Audio Clip

- Tarkanian on fielding regular calls from Lloyd Daniels.

-

Audio Clip

- Tarkanian on battling the NCAA and winning a $2.5 million settlement in 1998.

-

Sun Archives

- Columnist Ron Kantowski: Why Tark is missing from Hall of Fame (11-29-2005)

- Tark hangs it up (3-15-2002)

Jerry Tarkanian sits on a decades-old green vinyl couch near the front desk of the basketball academy that bears his name and plops his sore feet on a coffee table.

His three granddaughters yell from a balcony. Poppa! He glances up and smiles. He glares over his left shoulder at 23 concrete stairs.

“I hardly ever come here,” Tarkanian says. “I don’t like walking up those stairs.”

A nerve in his back is pinched. His legs have been bothering him for three years. He regrets starting physical therapy only a month ago. He fears back surgery.

Many are alarmed by his measured gait. He dreads fetching the mail in the morning. A friend recently insisted on a wheelchair at a function in Los Angeles.

He didn’t know which was worse, fans seeing him struggling with each step or sitting in a wheelchair. Embarrassing, he says.

Since giving a eulogy at the funeral of one of his former Rebels, Frank “Spoon” James, in early June, the 77-year-old Tarkanian has never felt so mortal.

“It won’t be long for me either,” he says. “I started feeling sad. Never thought about it before.”

It’s easy to see Vito Corleone, the aged mob boss played by Marlon Brando who gets melancholy in the sunset of his life, in Tark. He might slip an orange peel into his mouth to tease and chase his granddaughters at any moment.

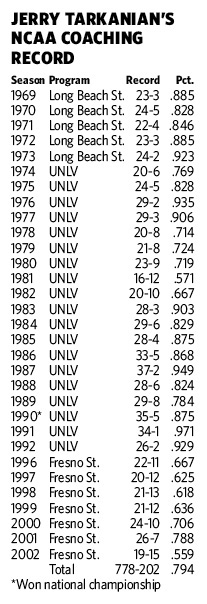

No doubt some believe Brando’s rogue character fits Tarkanian in other ways. The NCAA hit every program he touched — Long Beach State, UNLV and Fresno State — with sanctions. But he didn’t see it the same way and sued the NCAA. After a long battle, he won a $2.5 million settlement in 1998.

“Yeah, it was a big check,” Tarkanian says. “But it didn’t make up for all the problems they caused.”

In 1992, an infamous photo of three Rebels in a hot tub with a known gambler led to Tarkanian’s ouster at UNLV. He had knocked heads with longtime President Robert Maxson for years.

Athletic Director Dennis Finfrock, in poor health, recently said he regrets following Maxson’s orders to badger Tarkanian.

But many view Tarkanian as a beloved figure who gave disadvantaged and troubled kids a second, or third, chance, and guided the Rebels to four Final Four appearances. The 103-73 victory over Duke for the national championship in 1990 set a title-game record for margin of victory.

“Some of the happiest times of my life,” Tarkanian says. “I never anticipated we’d do what we did. I thought we’d be competitive. I never thought we’d win a national championship.”

A three-hour visit with the Godfather of UNLV hoops flies by.

Cell phones constantly interrupt his train of thought. So do the well-wishers who stop to pay their respects or thank him for something. He needs a ring on his pinkie for them to kiss.

The interruptions bounce the conversation like the basketballs on a gym floor.

Someone rings for his summer address near San Diego. Crates of white peaches and nectarines are soon on their way to his 10th-floor, ocean-view condo.

Tarkanian says he can’t wait to escape triple-digit heat.

He is a regular at the Del Mar racetrack, where friends such as Sid Craig — his college roommate at Fresno State and weight-loss magnate Jenny’s husband — circle horses in his program. A jockey even gives him tips. No, he says, he better not reveal the rider’s name.

On Tuesday mornings, former basketball coaches Pete Newell and Bill Frieder, current San Diego State boss Steve Fisher and other coaching friends meet at the track to shoot the breeze.

Back at the Tarkanian Basketball Academy, former TCU forward Shannon Long walks by and extends a hand. Remember me, Coach? We went to the Piccadilly Deli in Fresno on my recruiting trip.

You screwed up by not coming, Tarkanian says.

“I did screw up,” says Long, laughing. “Good to see you. I didn’t mean to cut you off.” He laughs as he pushes a glass door and walks outside.

Tarkanian beams about his family’s annual summer reunion, held a few weeks ago at Mammoth Lake in California.

Forty-three Tarkanians attended. He and his brother, Myron, mostly sat by a pool, ate Armenian staples shish kebab and grape leaves, and watched their 18 grandchildren frolic.

Danny Tarkanian, Jerry’s eldest son, brought two scrapbooks to reminisce about his father’s Long Beach State days. Instead, he watched his dad slowly flip through them.

“It was probably as much fun as I’ve had in the last five years,” Tarkanian says. “It brought back memories. In a lot of ways, what we did there was better than what we did here (at UNLV). We had no money.”

Tarkanian taps his cell phone. He just missed a call from Lloyd Daniels, the Brooklyn playground legend who was recruited by Tarkanian but was caught trying to buy cocaine from an undercover police officer in Las Vegas.

Wanted to say hello, Coach, Daniels says. Hope you’re doing well. Thinking of you. Take care, Coach.

Daniels never played for Tarkanian at UNLV, but Tarkanian brought Daniels with him when he briefly coached the San Antonio Spurs. Daniels played in the NBA for parts of five seasons.

He has two children in New Jersey and coaches a youth team he named the Runnin’ Rebels. He calls at least once a week. Tarkanian hands over the phone.

“It backfired on me, totally,” Tarkanian says. “I didn’t know he was in the drug scene. He couldn’t get out. It almost killed him. Now he has his life in order. I’m so proud of him.

“He says I saved his life. He says that meant more to him than anything. He just keeps thanking me, over and over. He says, ‘Coach, I love you. You did so much for me.’ ”

Tarkanian returns to his health. He has six heart stents and was so tired from medication that he refuses to take prescription drugs or any pain relief for his pinched nerve.

Therapist Carolyn Vanzlow puts him through a battery of stretches and balancing exercises that, he hopes, will alleviate his pain.

“She thinks she can help,” he says. “At my age, I don’t want to have back surgery. Other than that, I’m OK. Beats the alternative, I guess.”

Radio shows in Fresno and on the Sirius satellite network keep him busy, as do annual trips to the National Association of Basketball Coaches’ convention at the Final Four.

In San Antonio last spring, he roomed with close friend and ex-Maryland hoops coach Lefty Driesell, whose legs were sore and whose back was bothering him.

“We were hobbling around,” Tarkanian says, “and I’m thinking, ‘Isn’t this something?’ ”

Tarkanian books about six speaking engagements a year. His motivational theme always centers on pride.

“If you can make them proud of their organization and have them believe in themselves, then it’s easy to motivate them,” he says. “It’s difficult to motivate disgruntled people.”

College football motivates Tarkanian, who makes plans to see the Miami-Florida State, Alabama-Mississippi and Georgia-Arizona State games when his travel agent rings.

The Mtn. cable TV station calls to arrange an interview with him for a Legends series, and film outfits in Los Angeles and San Diego want to produce Tarkanian documentaries.

Tarkanian’s legacy, he says, is for others to determine.

To the delight of many veteran Rebels fans, Charlie Spoonhour and Lon Kruger have embraced Tarkanian, inviting him to every practice and game over the past six years.

He often has lunch at an Orleans coffee shop with Spoonhour, ex-Hawaii coach Riley Wallace and former UNLV Athletic Director Brad Rothermel.

Another ex-boss, former Long Beach State Athletic Director Fred Miller, rang around Christmas. Just calling the people who meant a lot in my life, Miller said. I’m getting sentimental. After he hung up, Tarkanian dialed Driesell, announcers Billy Packer and Dick Vitale, and former assistant coach Tim Grgurich and repeated the line.

Spoon James is still on Tarkanian’s mind. He says he believes in an afterlife. He has outlived six former players. A True Rebel. Yeah, he says, maybe that’s an appropriate tombstone.

“I’m in the overtime of my life,” Tarkanian says. “It’s a tie game. I hope we can keep winning. I want to get into that second OT.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy