Vincent F. Gordacan, president and chief executive of Bio-Fine Pharmaceuticals, is one of many Las Vegans who invested money with VesCor Development, a company run by Val Southwick. Gordacan says he saw half of his monthly income evaporate when he lost the money he invested with VesCor.

Sunday, July 6, 2008 | 2 a.m.

By April 2005, when the deal was inked, the signs of trouble were everywhere if anyone had bothered to look.

Twice in 1992, the Utah Division of Securities found that businessman Val Southwick had sold fraudulent securities to Utahans.

Two years later in Nevada, Southwick agreed to pay a $50,000 penalty and to stop doing business after the state Securities Division alleged that he had illegally sold $4.3 million in unregistered securities.

Court records contained civil suits that had been filed against Southwick over the years in Utah, Nevada and elsewhere.

Everything was publicly available.

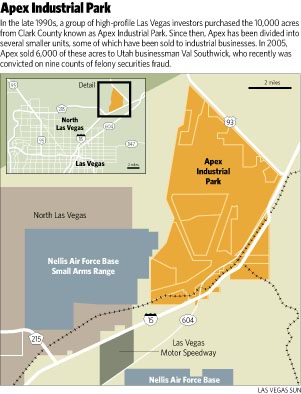

So how is it that in April 2005, a group of high-profile Las Vegas investors, including Mayor Oscar Goodman, went into business with Southwick? They agreed to sell him 6,000 acres in Apex Industrial Park for a whopping $123.6 million.

The deal soon fell apart, but the big-name investors were secured and made $16 million on the deal before getting their land back.

A host of smaller investors weren’t so lucky. Lured by Southwick and his company’s deal with Apex, those investors lost nearly everything.

Southwick was a real estate scam artist who preyed on the elderly. At the same time he was dealing with Apex, he was operating a massive Ponzi scheme in which he ripped off more than 800 people beginning in the early 1990s in Utah, Nevada and several other states to the tune of $180 million.

Southwick pleaded guilty in March to nine counts of felony securities fraud stemming from that scheme. On June 12, a Utah judge gave sentenced him to one to 15 years on each of the counts. Southwick is expected to spend a minimum of nine years in prison before he is eligible for parole.

Among the people he burned badly is 73-year-old Vince Gordacan, a Las Vegas pharmaceutical researcher. Gordacan says he saw half of his monthly income evaporate when he lost the money he invested with Southwick’s company, VesCor Development.

“To be really honest with you, I don’t know how I’m going to pay my rent,” Gordacan told the Sun.

The initial group of Apex investors who could be reached for this story, including Goodman and Tony Tegano, the founder of Tango Pools, said they were only passive investors who had no knowledge of Southwick’s misdeeds. In a recent deposition, Apex’s longtime property manager said essentially the same thing.

The manager, Adam Titus, who reports to Apex’s board of directors, said in the deposition that a background check on Southwick was conducted before the April 2005 sale.

Apex Holding Co. “did not learn anything during that time period ... that caused it not to go forward with the sale,” Titus said in a March 21 deposition in a U.S. Bankruptcy Court case. That case involves the Chapter 11 trustee who now has control over the Southwick companies that filed for bankruptcy in recent years in Nevada.

Neither Titus nor his Las Vegas attorney, Tina Yan, returned calls seeking comment.

Titus, by the way, worked for a VesCor-related company in 2005 and 2006 while also working for Apex through his own company, Industrial Properties Development.

According to Titus, the research into Southwick and VesCor was done by an Apex attorney named George Ralphs, a Las Vegas real estate lawyer.

Ralphs told the Sun that his background search on Southwick consisted of one business database search and one call to a friend in Utah. The database search yielded nothing, as neither Southwick’s nor VesCor’s name came up, Ralphs said. Likewise, his friend provided Ralphs with little pertinent information, he said.

Ralphs didn’t check any court files, didn’t call the securities divisions in Utah or Nevada or do any other checking up on Southwick. He said those are not normally things one does for a real estate deal, even one for 6,000 acres and $123 million.

“There’s not a lot of risk” for his client, Apex, in a deal like this, he said. “It’s an installment sale and we got a down payment.”

Plus, Apex was protected by a trust deed that allowed the company to foreclose on the property and get back the land if Southwick missed payments — which is exactly what happened when VesCor filed for bankruptcy.

It’s unclear exactly how Southwick and Apex came to be in business together; those who know aren’t talking.

The trustee in the Chapter 11 bankruptcy, Miami-based attorney Lewis Freeman, said in a May 12 court filing that he is suspicious of both Southwick and Apex.

In the first few years after the Apex investment group purchased the 10,000 barren acres near Nellis Air Force Base, it managed to sell about 40 percent of the land to real estate speculators and industrial businesses, according to Freeman’s research. By late 2004, Freeman wrote, the investors already had done well, more than doubling the roughly $18 million they had ponied up.

Southwick and VesCor then offered to buy the remaining land.

Freeman accused Apex of going into the deal with VesCor knowing that VesCor could never make good on the contract. Apex went along anyway so that the original investors could pick up the hefty $16 million down payment, attain favorable capital gains tax rates and still have the comfort of knowing they could reacquire the 6,000 acres “for nothing” when VesCor couldn’t make its payments, Freeman said.

There was conning going on, Freeman speculated in the court filing. He just didn’t know which party was conning which.

“In conclusion, my investigation is incomplete as to whether Southwick/VesCor were scammers that got scammed or just greedy fraudsters who reached for the sky and fell on their face,” Freeman wrote.

At his weekly news conference June 12, Goodman hotly denied the implicit accusations.

All Apex was trying to do — all he was trying to do — was make money through a legitimate deal, the mayor said. Goodman said repeatedly that he had no idea who Southwick was and that it is unfair to expect him and other passive investors to know about the sins of those with whom Apex was doing business.

“I made a legitimate investment before I was the mayor,” he said. Goodman’s involvement with Apex dates to the early 1990s. He became mayor in 1999.

Goodman said that if he’d had suspicions about Southwick at the time of the VesCor sale in 2005, he would not have agreed to do business with him.

“As far as I was concerned it was a legitimate company making a legitimate bid, and I was ticked off that they, uh, I think they went into bankruptcy or something,” Goodman said. “They didn’t pay me. That’s all I ... cared about.”

Goodman said that his original investment of roughly $700,000 gave him a 4 percent share of the Apex deal. He said he has since invested another $2 million, for a total investment of $2.7 million, and that he’s made $1.6 million in profits so far.

He stood to make about another $5 million if Southwick had followed through with his payments to Apex.

Tegano, the Tango Pools founder who originally bought into Apex for the same percentage as Goodman, said the investors didn’t know anything bad about Southwick prior to the deal.

“We were just looking to make money,” Tegano said. “Never heard a word about that guy.”

In addition to Goodman and Tegano, the Apex investors included prominent developers Peter and Tom Thomas of the Thomas & Mack Co., Ralph Engelstad, the now-deceased owner of the Imperial Palace, developers Joanne and Andrew Levy and Ed Hoffman, retired advertising executive Rod Reber and former Southern Nevada Paving owner Floyd Meldrum.

None of the other investors could be reached for comment.

Titus, the Apex manager, said in his deposition that Apex had a total of 21 investors. The group was put together by former Las Vegas City Councilman Al Levy in the early 1990s.

The deal stemmed from a 1989 congressional action that allowed Clark County to purchase 21,000 acres, including the 10,000 acres later acquired by the Apex investors, from the federal Bureau of Land Management.

The goal was to create an industrial park to house businesses such as power plants and manufacturers that would be unsafe in residential neighborhoods. The idea was spurred by a 1988 explosion at a rocket fuel plant in Henderson that killed two workers.

According to reports at the time, Levy, who has since died, approached the county in 1995 about the possibility of a private group’s taking over 10,000 acres.

In 1999, the Apex investors received the final go-ahead to purchase the 10,000 acres from the county for about $9 million. The investors then spent about another $9 million on “soft costs” such as legal fees and environmental and engineering studies, according to Freeman’s court filing.

Southwick came along in 2004. It’s unclear what he wanted to do with the land, if anything. Southwick’s Salt Lake City-based attorney, Max Wheeler, did not return a call.

According to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which filed a civil action against VesCor and Southwick the same day in February that Utah prosecutors filed their charges, Southwick, 63, never moved to develop the industrial park beyond subdividing the land and raising investor funds.

Southwick’s Ponzi scheme was typical of such scams, according to the SEC. He sold promissory notes and other securities to finance real estate projects he developed and others he only proposed.

But rather than invest most of the money, he applied “a significant amount of money to pay VesCor Companies’ promised returns to earlier investors,” SEC officials said in their Feb. 6 papers.

Eventually, Southwick’s scheme imploded, along with the vast network of companies he created to support it.

There was a great human cost to Southwick’s crimes, officials and victims said. Some of the hardest hit were the many seniors whom he frequently targeted. Often families’ savings went down the drain when Southwick investors tried but failed to get their money back.

“I’ve never seen a case where we had a greater victim impact,” Utah Chief Deputy Attorney General Kirk Torgensen said after Southwick’s recent sentencing. “These people were devastated.”

Although Southwick did most of his business in Utah and was prosecuted there, almost as much impact was felt in Southern Nevada.

According to the Utah Division of Securities, of the roughly 800 VesCor victims, 300 cooperated with state authorities, said division analyst Jennifer Korb. Of that smaller pool, 113 victims were from Nevada — all but two from the Las Vegas area.

Those smaller investors were not necessarily told their money was going directly into Apex. But the Apex deal did boost the VesCor portfolio — on paper — and as such, gave the company more legitimacy.

One of Southwick’s investors was Alicia Foutz, a Las Vegas dental hygienist born and raised in the area, who said she first invested some of her inheritance and savings through a Southwick associate named Bill Hammons in 1999 or 2000.

Hammons had been bishop of Foutz’s Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints ward in Las Vegas. Foutz said she felt reassured about him because she sensed that he had already been quite successful in real estate.

Foutz, 64, said that with Hammons’ encouragement, she liquidated stocks and bonds, and even transferred her retirement savings into a VesCor-controlled bank to make it easier for the money to be transferred regularly to VesCor coffers. She gave a total of $1.3 million to VesCor, money she may never see again.

The interest checks from VesCor slowed in 2005 and stopped completely the following year, Foutz said.

Foutz said she had planned on using her VesCor investment money to augment her retirement, to travel and to make charitable donations in her will. The loss of the money forced her to go into debt and drop her health and disability insurance for a long period.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Foutz said.

Neither Hammons nor his St. George, Utah-based attorney, Adam Dunn, returned calls.

Another defrauded investor, Gordacan, the pharmaceutical reasearcher, said he was first approached by Hammons in 2001 and persuaded to invest $100,000 in one of VesCor’s Nevada properties, the Siena Office Park medical complex in Henderson. The following year, Gordacan invested $75,000 more.

In the next few years he received several monthly interest payments. Those checks made up half his income, with his and his wife’s Social Security checks making up the other half, he said.

Then in 2005 he was notified by his bank that the VesCor checks had started bouncing. He found that he couldn’t gain access to his original principal, the $175,000. It was, for all intents and purposes, gone.

Gordacan said he received a letter in 2006 from VesCor noting that the overwhelming majority of his investment money actually went to buying the Apex land, not the Henderson office park as promised. Gordacan said he had never heard of Apex before that letter.

Now that name has joined Southwick, VesCor and Hammons on the list of those he says left him so broke that he can’t afford to hire a lawyer to sue them.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy