Tuesday, Feb. 19, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Oregon Mayor Unnerved by Lingerie Photos (1-19-2008)

- Flawed sex offender tracking leads to wrong door (11-18-2007)

- Dark side of the Internet revolution (8-9-2006)

- Editorial: Personal space in a public venue (1-18-2006)

Beyond the Sun

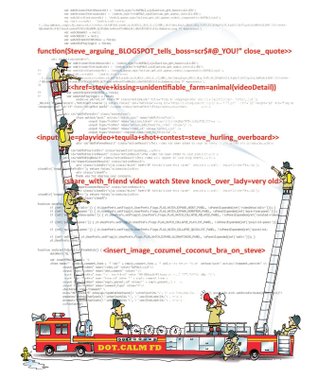

Cheating on his wife was not Steve’s first or worst mistake. His real problem was he had married a woman whose brother had a flair for revenge.

Steve’s brother-in-law — we’ll call him Tim — didn’t squeeze apologies out of the adulterer in a boozy back-alley fight, didn’t key his car, slash his tires or even help his sister hire a shark of a lawyer.

What Tim did was more modern — and meaner. He took his rage online, where it could run rampant. On Web sites and in chat rooms, Tim called Steve a cheat, a liar and worse. Wherever he could, he soured Steve’s name and shamed him online for the world to see.

And when he was done, instead of feeling triumphant, Tim realized he felt really, really bad. But it was too late. Tim’s fury had become bigger than the brother-in-law himself. His hate had been cast so far and wide in the Internet ether that he couldn’t take it down or take it back.

So he hired someone else to: ReputationDefender, a California company that specializes in the erasure of Internet embarrassments and harassment — a crime scene cleanup of the digital age. Tim hired the company to seek out and destroy all his nasty postings, and he’s just one of the company’s thousands of clients.

Want to eighty-six those blurry photos from the Antigua nudist resort, the ones the boss saw? Dying to bury the online diary an ex was writing, the one that details the drugs you two did together? Desperate to spike the nasty little posting on that blog that made you sound nuts? Hoping to hide that Web site someone started just to make you look bad?

It happens all the time, ReputationDefender Chief Executive Michael Fertik says.

“Maybe you just want to establish your good name on the Web,” Fertik said. “Maybe you’re doing it to bury some bad stuff.”

A lot of people want to do one or the other or both.

The company launched in October 2006. One year later, ReputationDefender’s revenue was up 2,500 percent, and the company had made its first million dollars, Fertik said.

Basic services are just shy of $10. More complicated cases cost more. ReputationDefender recently set its base rate for challenging jobs at $25,000.

It has been successful enough that copycat companies are cropping up — defendmyname.com, reputationhawk.com, chatterguard.com and so on.

ReputationDefender has had 28 clients from Nevada, 27 of whom refused to comment. For the same reasons Steve and Tim don’t want their real names online, Nevada’s Internet ashamed and remorseful didn’t want to talk about it. They hired Fertik to make their names vanish, not appear in newspaper articles.

Reno student Abel del Real Nava, 18, was the only Nevada ReputationDefender client willing to talk. He signed up for the company’s $9.95 monthly service, MyReputation. All it does, really, is scan the Internet for information about you. If you don’t like what it finds, the company will destroy it for $29.95. Combing the Internet, the company came up with a heated online exchange del Real Nava had with someone over a decidedly uncool thing to argue about: the virtues of Macintosh vs. Microsoft.

Of course, that he cared enough to argue about it, and then duked it out online, is evidence of why Fertik’s company can’t help but grow. So much of what matters to a kid like del Real Nava happens on the Internet, or is in some way related to technology: his MySpace page, the Web sites where he gets his news, the smart cell phone that allows him to be online all the time. But a life lived online can haunt you forever, and del Real Nava was afraid a prospective employer would google his name (as one in five does, studies show) and refuse to hire him when he or she saw the colorful language he’d used to make his point about a computer brand.

ReputationDefender got rid of the dialogue. Fertik won’t say how, except that it’s a guarded combination of asking nicely and skewing Internet search schematics. A “math problem” that makes things go away, he says. Think of it as the Internet mafia’s cement shoes.

“If you are ruining other people’s lives,” Fertik said, “prepare for the consequences.”

When Geoffrey VanderPal ran for secretary of state in 2006, the Las Vegas financial planner learned quickly that his campaign wars would be waged online. A series of nasty blog entries, and comments left by readers of online newspaper articles about the secretary of state race, cut VanderPal to the quick. He was mocked, his credentials were questioned, he lost the race.

But it didn’t end. When the election was over, VanderPal told The Washington Post, the Internet attacks he’d weathered still scared away business.

VanderPal hired ReputationDefender, who contacted the particularly cruel bloggers, according to press accounts, and asked them to stop. They didn’t. In fact, the effort made things worse, so the company went to work manipulating the Internet so that bad information about VanderPal was “buried.”

At the time, ReputationDefender was charging only $10,000 for this type of premium service, although it’s unclear how much VanderPal paid. He did not return calls for comment.

What is clear is what happens when you google his name: A few negative blog posts come up, but they are outnumbered by a string of positive Web sites that appear, although Fertik won’t confirm it, to have been created for the express purpose of drowning out the others.

Half the time, people do the damage to themselves. Like the woman who wrote long online journal entries about her eating disorder, only to find she couldn’t take them down when she wanted to. Or the student who wrote about his depression while studying clinical psychiatry. When he graduated, people searching for his published research online would find out about his own struggles with mental illness. And then there are the scads of people who let their photographs loose on the Internet, only to see them pop up in undesirable places. One of Fertik’s clients found her face superimposed on pornographic photos. It was the work of an ex-boyfriend.

Other times, it’s just happenstance.

John got married twice — the first was a mistake and the second was fine, except for one thing: When you googled John’s name (which he doesn’t want printed, for fear you’ll do it), the Internet search returned an account of his stunning wedding ceremony. His first stunning wedding ceremony, which didn’t make his second wife too happy. She called ReputationDefender. Now she’s pleased.

And occasionally it’s just pure evil, Fertik says. People who delight in the anonymity the Internet affords and attack like dogs.

Nikki Catsouras, a California teenager, was killed when she drove her father’s Porsche at 100 mph into a concrete toll plaza after clipping another car on Halloween. Highway Patrol officers took photographs of the accident, which was wildly gory, and e-mailed them around the office.

Then they appeared online.

Someone sent them to Catsouras’ family and put them on a MySpace page created in the teen’s name, and quickly they were on thousands of Web sites. Catsouras’ sister was taken out of school for fear someone would slip the photos into her locker, while other family members stopped using their e-mail entirely.

They hired ReputationDefender, which has gotten the photos taken down from hundreds of sites, although far from all of them.

“Some of the worst creeps work very hard to remain anonymous,” Fertik said, “and sometimes you have to work very hard to uncover them.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy