Clark County Family Court Judge William Voy presides over the juvenile sex offender calendar at the Clark County Family Court Building in December.

Sunday, Dec. 7, 2008 | 2 a.m.

No. 1

I realize that if I keep going down the path that I'm going I'll only end up dead, hurt, or constantly here. This not how I pictured myself or my lifestlye future being. I want to change for myself, and I've realizzed that I've degrated myself ... I can't keep crying, hoping and wishing things didn't happen I can't change my past. Mom I'm sorry I hurt and abused you and every other person that cared, and I didn't listen

No. 2

I cannot ask and beg you to release me, because I know that it all depends on my actions ... I dont want this letter to seem like a cry for help but I would like you to know that I am willing to do what I have to do not just to get behind the locked doors and barbed wire but also so I can make a improvement in my life. I believe that this is a wake up call for me to get my life on track.

No. 3

I am just writing this Little Letter to tell you why I Think I shooud be in chilldren of the night * here are the reasons. They will work on my prostutoson, & They will take me to my drug class's and parenting' class's They will help me get a job and a appartment and get my (GED). They have a good support system and I can continue my counseling and I can werke my plan to get my son back.

No. 4

I went home and I manage to find a job that payed under the table. Because Im not a citizen I was able to find a better job but after they went bankrupt. I had no other job options because of my legal status ... During the time I was working I complete prorroll successfully. I was discurage and frustrated ... my desperation led me into making a mistake ... I’m not saying what I did was right ... It was wrong.

* Children of the Night is a program dedicated to helping juvenile prostitutes. In Los Angeles, the nonprofit runs a 24-bed home that provides schooling and counseling.

Face to Face: Blind Eye?

A new report says Las Vegas' commercial sex industry creates a culture of tolerance that allows teen prostitution to flourish. Jon talks with Family Court Judge William Voy and UNLV Assistant Professor Alexis Kennedy about what's being done to address the complex problem.

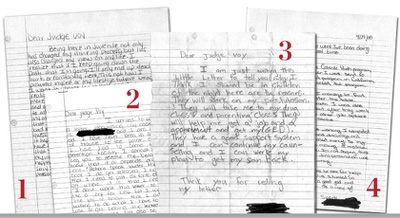

Teenage prostitutes write Judge William Voy letters from detention before sentencing. Their pencil-scratch pleas for leniency are composed on ruled notebook paper, with spelling and grammar so shoddy it often speaks louder than the content of the letter — revealing the circumstances that lead a teenage girl into prostitution, one strained sentence at a time.

“I knew that the life stile I was living will probably kill me. But I liked to tell my self it wouln’d happen to me. When I was yunge I had dreams of becoming a model. Inted I became a prostitud.”

Instead she became a prostitute, one of hundreds who land before Judge Voy in his juvenile prostitution court, held every Wednesday morning, 9:30 to 11.

Not every girl writes a letter, Voy says. Usually it’s the ones who are slipping into the system, back for a second or third time. They hope Voy won’t send them to a reformatory school in rural Nevada, with strict rules and dress codes and constant supervision — a teenager’s nightmare.

That’s just what they are: teenagers. Some are younger: 12 years old. This is obvious in the sampling of letters Voy gave to the Sun, with identifying information blacked out. The compositions look like they’re written by middle-school students — on subjects for adults.

No matter how old, Voy says, all of the girls age quickly in “the game” — prostitution parlance for the flesh trade.

“I dont wont to be like this forever I wont to make something of myself. I dont wont to be in the game anymore i gave it up im focuse on something else.”

Certain similarities flow through the letters, and the overlaps paint a broader picture of juvenile prostitution. Many of the letters are written by girls who want to stay in Clark County, not just because probation or group homes are preferable to long-distance boarding, but because this way they can be with their children — the babies of babies.

“They will take me to my drug class’s and parenting class’s They will help me get a job and a appartement and get my GED. They have a good support system and I can continue my counseling and I can werke my plan to get my son back.”

Another:

“I really want to do good. Not just for the sake of me. But for the sake of my baby well being too. And judge Voy just let me tell you. Now that I got somebody els to look after I cant be quick to jump and make all the decisions. Because I know the courts can take me baby from me. I’ll be damned if I get my baby tooken for my wrong doings and all my wrong stupid mistakes.”

Sixty percent of the juvenile prostitutes who come into Voy’s court are from out of state, 60 percent from California. They land in Las Vegas because it’s part of the prostitution circuit, Voy said, teenagers hopping from city to city, looking for clients. The teenagers who get caught are only a small fraction of the unknown total — the kids who solicited undercover vice cops.

In letters, they know they’ve disappointed the judge.

“I know you’re tired of seeing my face ... I hope you can forgive me for what I’ve done if you can find it in your heart to forgive me for breaking my promise to you and me ... P. S. Please 4give me for messing up.”

There aren’t many options — sending a girl to state boarding school is the judge’s last resort. Otherwise, Voy’s sentencing options are a group home, a shelter, some out-of-state programs or juvenile hall. Voy has been trying to drum up support to build a safe house for sexually exploited youth in Clark County, but he can’t convince enough people to get behind the cause. Teenagers from out of state are often shipped back to their home jurisdiction, where what happens is out of Voy’s hands until they return, and they often do.

“I know you are wondering why you are looking at me like why are you back in my court room ... I just wonted to have a little fun for a change ... I end up back in the same position that I was trying to get out of. I can admit what I have done was wrong and I can accept the fact that I was wrong doing.”

Other letters give quick glimpses that don’t need explanation:

“The past two weeks have been the worst in my life. Sir you dont know what I went threw the 2 week I was a runaway. I DID want to go home, but I was afraid to go home because my little brothers life was being threatened by a man that wanted to pimp me.”

Another:

“I believe I am trying to escape reality I am running from my problems by using and I need some serious counseling. Ive never had any kind of help since the first time I was raped at 10 and my life has become unmanagable ever since. There is a circle I keep going in because of my dishonesty about my drug use ...”

And another:

“I sold my life for money dreaming of a better life and that hopefuly the game will get me out. Out of my strugles. But inted it brought pain ... now I see myself lying dead.”

Voy uses the letters to gauge what the girls are thinking, whether they see they’ve made serious mistakes, and whether they’re stable enough for certain programs or need more comprehensive care. Most of the letters are sincere, but sincerity isn’t enough, Voy says. It’s a matter of whether they have the capability, the emotional stability, and the tools to pull themselves out of a criminal justice system that seems to tug them in.

“This is not how I pictured myself or my lifestlye future being. I want to change for myself, and I’ve realized that I’ve degraded myself. I want more for myself. I want to move forward and not keep making the same mistakes.”

Few of the letters are consciously about reflection; most are about getting out of boarding school.

Sometimes the judge gets waves of letters that exploit the same angles for the judge’s favor. He chalks this up to kids talking with each other in the detention facility, comparing notes on what worked and didn’t. What kept one girl out of reform school, what got another sent to a program in California. Sometimes, the judge says, there’s manipulation.

“P.S. If The Lord Can Forgive Me You Can To!”

Voy sighs heavily when you ask him if some kids are in too deep to go after with any success. If you don’t have hope, the judge says, you can’t do this job. And he’s not the only person nursing private hopes.

“I got my mind made up this time im going to school maybe even collage hopefully ... I have a chance to make it right that what im going to do. I now cant nothing get in my way.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy