Josh Gilbert, left, and his mother, Nancy Gilbert, meet with Global Community High School Principal Mike Piccininni. Josh and his brother Angelo attend the alternative school, where they are doing well, after they were referred for expulsion from Eldorado High and then sent to a behavior school.

Monday, April 14, 2008 | 2 a.m.

For the past few weeks, Clark County principals have been recommending up to 100 students for expulsion each day, putting extra strain on a disciplinary system that many say has long been stretched too thin.

The School District’s daily volume of expulsion referrals is at an all-time high, according to Associate Superintendent Edward Goldman.

The increase is putting pressure on the district to find enough seats at its three continuation schools for expelled students and at its five behavior schools for students given less severe punishments. In the past, Goldman, who is in charge of the Clark County School District’s education services division, has been forced to close behavior school campuses to new arrivals until other students rotate out of the program. As of Friday, at least one campus was teetering on the edge of closure. No one’s knows for sure what’s driving the spike in expulsion referrals, but the main theories are:

• In the wake of school-related shootings, educators are more closely and critically monitoring student behavior.

• Pressure from parents and the community has schools taking a harder line with first-time offenders.

• More students are fighting, engaging in gang activity and being caught with contraband.

Whatever the reasons for the spike, it comes amid growing concerns that the district’s approach to discipline is falling short.

One bone of contention is the shuffling of students who have been expelled. Once those students’ time at a continuation school is up, they typically are not allowed to go back to the school from which they are expelled, so they are sent into a different school. Critics say that spreads the problem students throughout the valley, effectively ensuring that no school can remain immune.

In the wake of the recent spate of school-related shootings, Clark County Schools Superintendent Walt Rulffes said he has heard plenty of suggestions about how to improve campus safety.

“A number of people have told me to just throw the bad kids out and never let them back in,” Rulffes said. “But all that does is move the problem from the school to the streets.”

Still, he worries that the current system “is not good for the learning process,” Rulffes said. “Every time you break the continuity, there are setbacks.”

Also, the behavior schools were never intended to be a therapeutic setting, where the district would try to “fix” its troublemakers. Rather, the behavior campuses are more like depot stations, with students arriving and departing on a regular basis. The teachers’ primary goal is to keep the students on track academically. Whenever possible, intervention strategies such as character education are included in the curriculum, but it’s far from the main focus.

•••

There is scant data about students who pass through the district’s behavior and continuation schools. The district does not track their academic performance or behavior once the students return to a comprehensive campus, and there are no statistics showing dropout or graduation rates.

Goldman’s office does track recidivism. Of the more than 4,000 students referred for expulsion in the 2006-07 academic year, 17 percent were referred a second time for a new offense after completing a stint in a behavior or continuation school. So far this year, the recidivism rate is 22 percent.

The district has about 1,000 seats spread among its behavior and continuation schools throughout the district. The program has not added seats since Peterson Behavior Center opened in the northwest in 2002. Because of staffing limitations and safety concerns, Peterson’s enrollment tops out at about 200 students.

Students are not released early from a behavior program to make room for other students, Goldman said. But occasionally he has to tell principals that a behavior school campus is full, and no new students will be accepted. When that happens, principals are expected to handle the minor offenders themselves.

At Spring Valley High School, Principal Bob Geyre said he frequently has students transfer in after a stint in a behavior or continuation school.

“They come here, and immediately within two or three weeks they get into trouble and they’re sent out again to a behavior school,” Geyre said.

The behavior schools would be a better option if students stayed for the entire nine weeks, and had access to the intensive intervention programs and services that would improve their chances at success when they return to a comprehensive high school, Geyre said.

“Instead, we churn the same kids through, again and again,” Geyre said. “That’s the best we can do, because if we don’t, the whole system stops.”

•••

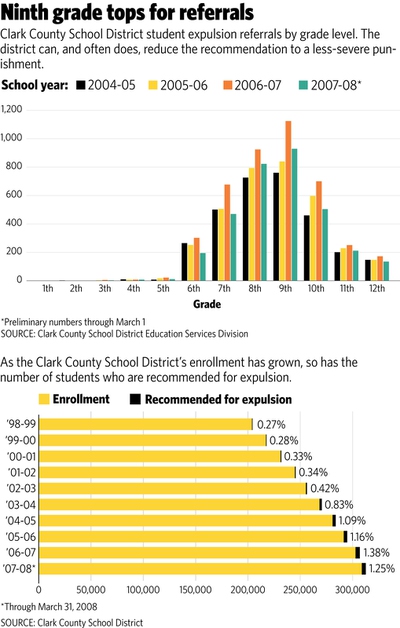

As of April 9, with two months remaining until summer vacation, 4,049 students had been referred for expulsion. The total for the entire 2006-07 school year was 4,188.

This year there were notable increases in two particular months.

With students only on campus for two weeks before leaving for winter break, December is typically a slow month when it comes to discipline problems. But in December 2007, principals referred 535 students for expulsion, compared with 344 in December 2006. One theory is that the Dec. 11 wounding of several Mojave High School students who were shot after getting off a school bus spurred the expulsion referrals.

The number for February, 590, was also up sharply from 2007, when 455 referrals were submitted. On Feb. 15, Palo Verde High School freshman Chris Privett was killed while walking home from school, allegedly by a schoolmate who fired at Privett from a passing car.

All expulsion referrals are sent to Goldman’s division for adjudication. The district can, and often does, modify a student’s punishment to something less severe than formal expulsion.

“You have to use discretion,” Goldman said. “Every case, every kid, is different. They are entitled to a hearing, and we look at their academic and disciplinary history. Otherwise, there wouldn’t be due process.”

Of last year’s referrals, 1,112 students were formally expelled and spent at least 18 weeks at one of the district’s three continuation schools.

Expelled students are not allowed to return to their home schools, but may apply for a trial enrollment at another campus. The remaining students referred for expulsion were spared the most serious punishment, and instead were sent to one of the district’s behavior schools. After serving their time, the students are assigned back to their home school or another campus.

Certain crimes, such as arson or selling drugs on campus, require an expulsion referral. Principals have more leeway, particularly with first-time offenders, when it comes to lesser offenses. An expulsion referral is not a requirement for a student to be sent to a behavior school.

District regulation does not require a minimum “sentence” in a behavior school, but it’s long been the practice to have students spend nine weeks, the equivalent of an academic quarter, away from their home campus.

The district measures the nine-week period beginning with the date of the infraction, not when student actually reports to the behavior program. If a school administrator lags in submitting the required paperwork, a student may end up spending two weeks at home and seven weeks in the behavior program. Four weeks is the minimum stay at a behavior school, Goldman said.

In addition to the behavior and continuation program, the district has about 1,800 seats in its alternative schools, for students who prefer a nontraditional program such as evening classes or independent study. Goldman said there is no shortage of students interested in the alternative schools, and he could easily fill twice as many seats.

The alternative schools are also popular with students who have completed a stint in a behavior program, but prefer not to return to a comprehensive campus. For some of them, it’s the best way to get a fresh start and leave behind the friends and bad habits that contributed to past mistakes.

•••

One alternative campus is Global Community High School, which was set up to help newcomers to the United States immerse themselves in English-language instruction. The school has a few seats set aside for native English speakers. For Maria Gomez, who was kicked out of Desert Pines High School in 2006 after getting caught with a tagging crew, Global Community has been nothing less than her salvation.

After finishing several months in a behavior school, Gomez wasn’t ready to go back to a regular high school. She had arrived at Desert Pines as a frightened freshman, overwhelmed by the school’s size. When a group of kids invited her to join them on a spray-painting spree after school, she agreed. Soon, she was a member of the crew.

“I was trying to fit in,” said Gomez, now a sophomore. “It was a stupid thing to do.”

At Global Community, she’s more interested in photography and world history than in what’s become of the crowd she used to run with at Desert Pines. She credited the personal attention she gets from her teachers, as well as the positive influence of being around other students who share her goal of graduating, for her turnaround. “I get good grades now,” Gomez said. “I want to become a lawyer and help people.”

Rulffes said he’s in favor of more alternative programs that might help steer students away from trouble and toward academic success. But “before we expand, we need to know the facts,” he said.

Acknowledging the dearth of statistics, Rulffes said he’s planning a study for this summer that would examine student achievement in the district’s behavior and continuation schools, as well as the associated costs. He’s also interested in exploring whether schools would benefit from having on-campus alternatives for behavior students, particularly those who commit less-serious offenses.

But like so many things, improvements will depend on the availability of funding. There’s a long line of students who need more programs and services, including the gifted and talented kids Rulffes said have been “under-challenged” for too long.

“The cost of the alternative programs can be shocking,” Rulffes said. “Before we put more money into it, we need some evidence that it’s working.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy