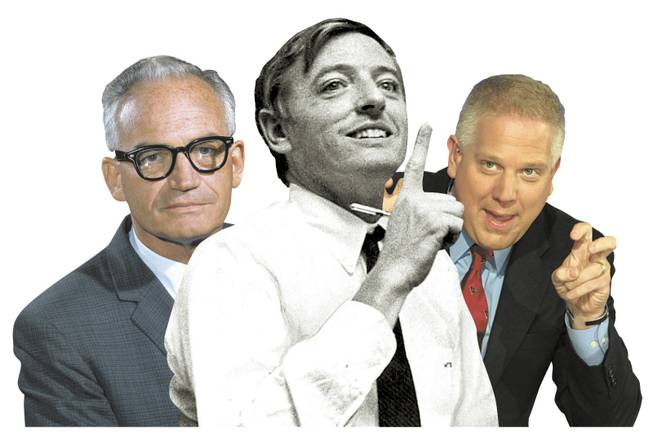

LAS VEGAS SUN PHOTO ILLUSTRATION

Current and past leaders of the conservative movement, from left, Barry Goldwater, William F. Buckley and Glenn Beck.

Sunday, Jan. 24, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- ‘Tea Party’ set turns out in Las Vegas at its anti-Harry Reid finest (1-13-2010)

- Grass roots or not, Nevada tea parties had assist (9-1-2009)

- Hundreds rally against Harry Reid, proposed health care reform (8-31-2009)

- Countering the hysteria (8-26-2009)

- Anti-tax advocates rally against spending, Obama (4-15-2009)

Sun Coverage

The federal government, under the guise of helping the mentally ill, is establishing a concentration camp in Alaska to house political opponents — a new step on the path toward totalitarianism.

Dan Smoot and other historical footnotes made the allegation in 1956, and it briefly became an obsessive cause of the right-wing grass roots, with each new allegation topping the last.

Perhaps this episode sounds vaguely familiar. That’s because Fox commentator Glenn Beck said last year he had tried but could not refute claims that the Obama administration was creating FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) camps that would house its political opponents.

Remarking on the camps and his failed attempt to “debunk” the allegation, Beck said: “If you have any kind fear that we might be heading toward a totalitarian state, look out. Buckle up. There is something happening in our country and it ain’t good.”

He would later correct his FEMA camp story, but by then, the myth had implanted itself.

Beck and the Tea Party movement of which he is a central figure are often portrayed as a new and exotic political phenomenon. Pollsters treat the Tea Party movement like a third political party, and indeed, it is especially popular at the moment among unaffiliated voters new to politics.

For voters — most recently in last week’s Massachusetts special election — who believe big government and big business are engaged in a corrupt marriage, the movement feels like a refreshing voice for average people who aren’t in those backrooms and so aren’t getting cut in on the deals, like during health care reform negotiations.

Indeed, Kay Lawrence, a retired art gallery manager who attended a Tea Party event in Las Vegas recently, voices this complaint: “We’re sick of these sweetheart deals.”

For all its apparent freshness, however, the Tea Party movement is neither new nor novel, historians and political scientists say.

It is firmly rooted, in its ideology, rhetoric and — there’s no polite word for it — its paranoia, in the post-World War II American right.

Every few years, usually though not always during a Democratic administration, the movement reappears, with a similar set of grievances: The expansion of government is moving us toward socialism; there’s been a dangerous weakening of the national security apparatus but also, paradoxically, the threat of police state provisions at home; an alien subversive of nefarious intentions, composed of cosmopolitan elites and corrupt “one worlders” has infected the government.

In the 1950s, conservatives were angered when their champion, Ohio Sen. Robert Taft, was shoved aside by Republican elites in favor of the moderate Dwight Eisenhower.

Kathy Olmsted, a University of California, Davis historian of the period, notes that they accused the one-time Supreme Allied Commander of being a communist agent, an allegation made repeatedly by candy tycoon Robert Welch.

Consider the far-right rallying cry during the presidency of Bill Clinton: Jackbooted government thugs were on the loose; American soldiers were fighting under the U.N. flag; the 1993 tax increase — and yet another failed attempt at health care reform — the marks of a closet socialist.

The most fitting parallel, however, may be the early 1960s, when right-wing activists believed the civil rights movement was the work of the Soviets and, as Ronald Reagan alleged, Medicare a push for socialized medicine.

“The tropes, the rhetoric, the cultural profile — there are profound similarities,” says Rick Perlstein, who has completed two books of a trilogy on the history of the conservative movement and is widely viewed by conservatives and liberals alike as its key chronicler.

Like President Barack Obama, John F. Kennedy was a “first” — the first Catholic president in a nation with a long history of anti-Catholic bigotry and conspiracy theories about powerful papists. Like Obama, Kennedy’s administration was staffed with Eastern elites from the best schools and largest corporations, all viewed warily by Sun Belt and rural Americans.

Another parallel, Olmsted says, the Tea Party movement is not unlike a right-wing activist group of the time, The John Birch Society. “The John Birch Society was extreme, but also connected to the Republican Party, and Republican politicians had to make a decision about whether they were with the movement,” she says.

Then there’s the paranoia: Before it was communist plots, now it is “death panels” and the belief that the administration is eager to seize guns.

Gun sales have skyrocketed since Obama’s election. In November 2008, FBI background checks for prospective gun buyers rose 41.6 percent compared with a year earlier, even though Democratic politicians have shown no interest in meaningful gun control in years and have blamed the issue for electoral losses in 1994 and 2000.

Even reasonable Tea Party activists, such as some from the recent Las Vegas event interviewed by the Sun, take it as given that Obama is a socialist. It hardly seems to matter that a significant chunk of the stimulus was a tax cut, or that his chief economist is centrist Larry Summers, or that the bailouts of the auto and banking industries began under President George W. Bush, or that Reagan favored the bailout of Chrysler in 1980, or that Reagan raised taxes to save Social Security.

Obama is a socialist, if he’s not a fascist, a Nazi, or a totalitarian.

Like the Tea Party movement, this paranoia is not new, nor is it confined to the right.

In 2005, as the left pulled at its hair over imagined Bush conspiracies, conservative columnist David Brooks recalled Richard Hofstadter’s seminal 1964 essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.”

“The paranoid spokesman sees the fate of conspiracy in apocalyptic terms — he traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds, whole political orders, whole systems of human values,” Hofstadter wrote. “He is always manning the barricades of civilization.”

As for the enemy, “He makes crises, starts runs on banks, causes depressions, manufactures disasters, and then enjoys and profits from the misery he has produced.”

And, “He is a perfect model of malice, a kind of amoral superman — sinister, ubiquitous, powerful ...”

David Brown, a Hofstadter biographer and historian at Elizabethtown College, notes that Hofstadter places the populist right in the context of America’s long tradition of paranoid political movements that effectively “magnify the opposition.”

The use of the clinical term “paranoid” to describe the president’s opponents is surely condescending.

“It’s condescending, but it also happens to be true,” says Michael Munger, a Duke University political scientist who is a libertarian and has been a keynote speaker at a number of Tea Party rallies.

He says we’ve reached a tipping point of paranoia and conspiracy mongering, fed by two trends: loss of credibility of official sources culminating, as far as conservatives are concerned, with this administration; and the profusion of media outlets that feed on conspiracy and paranoia.

Indeed, there are differences between the current Tea Party movement and its ancestors, especially in the media.

Whereas there were once a handful of powerful media voices, now there are thousands.

Perlstein notes that establishment media of the early 1960s acted as a filter against extremism. Walter Cronkite, for instance, would never countenance the likes of Orly Taitz, a leader of the movement to prove Obama was born in Kenya. And, yet, there she is on the cable networks.

As Olmsted notes, “With cable, there’s an endless appetite for feeding the monster. And with Fox, it’s made to order.”

There was another check on the extremism of the early 1960s — the conservative movement itself. As conservative historian Sam Tanenhaus and Perlstein have noted, the godfather of the conservative movement, William F. Buckley, acted as de facto disciplinarian, casting out the Birch Society and the radical libertarian Ayn Rand.

Buckley is dead, and there are no voices of such singular influence who could play the same role.

Also different: The Republican Party of the early 1960s had a strong contingent of moderates or “Rockefeller Republicans” who favored civil rights and opposed the destruction of the New Deal.

They are gone now, as much a relic as Brylcreem, which makes “purifying” the party an ever more extreme proposition.

What is unknown at this point is whether the Tea Party will have the same lasting success as the conservatives of the early 1960s.

Whatever their now-discredited views about Medicare and the civil rights movement, conservative activists were effective — they overthrew the Republican Party’s Eastern establishment and nominated then-Sen. Barry M. Goldwater in 1964.

The Cuban Missile Crisis, the assassination of Kennedy and Goldwater’s own rhetoric — “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice!” — scared voters and led to a landslide for Democrats in 1964.

But Goldwater’s “The Conscience of a Conservative” remained a founding text of the modern movement, a work of elegant prose and cogent argument, while a speech Reagan gave just before the 1964 defeat would live on like a Homeric poem.

And just 16 years later, the Reagan Revolution was on.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy