An aerial view of Callville Bay Resort & Marina on Monday, Aug. 18, 2014, at Lake Mead.

Monday, March 21, 2016 | 2:01 a.m.

The impact of pipes

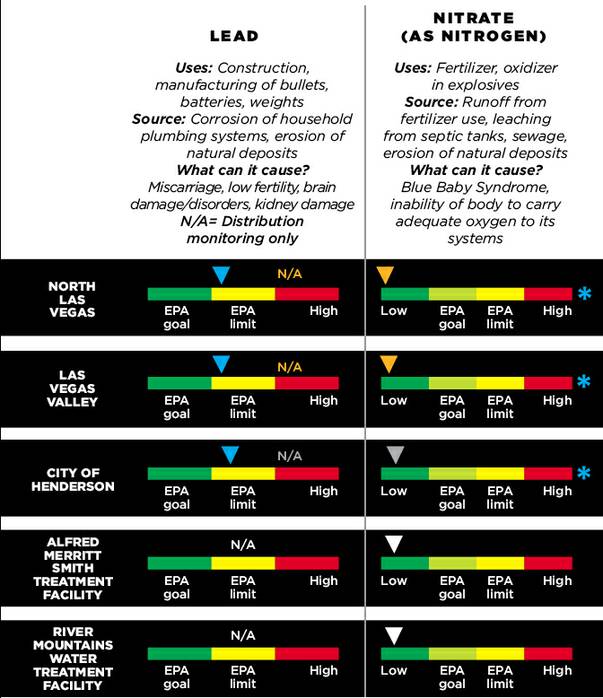

Unlike Flint, lead pipes are not an issue in Southern Nevada, where the region’s comparatively new water system is comprised of copper pipes. Copper can leach into drinking water through plumbing, but the valley’s water agencies take steps to protect pipes so they don’t corrode and release copper particles in the water. Copper and brass fixtures, faucets and fittings also can be a source of contamination. The amount of copper in your water typically depends on the type and amount of minerals in the water, how long the water stays in the pipes, the amount of wear in the pipes, the water’s acidity and the water temperature.

Southern Nevada water officials followed with interest the unfolding story of contaminated drinking water in Flint, Mich. It was a case study in what not to let happen here.

When Flint officials made a cost-cutting decision to switch water sources, water from the new source, the Flint River, corroded the city’s aging lead pipes, exposing 8,000 children 6 years old and younger to unsafe levels of lead in their drinking water. Lead is a toxic metal; exposure to it has been linked to nervous system damage, learning disabilities, hearing impairment and other health problems.

Federal and state officials declared a state of emergency in January in Flint, and several lawsuits have been filed against the government as a result of the contamination.

Flint is an extreme example, but the city’s cautionary tale has trickled to Southern Nevada, where we grapple with drought, a finite water supply and the battle to keep America’s nuclear waste outside of our backyard.

The Flint situation “is an incredible blemish on the reputation this country has enjoyed around the world of being one of the most reliable and progressive countries in the world of water-resource management,” Pat Mulroy, former head of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, said this year.

Flint has left officials here and across the country scratching their heads, wondering how everything could have gone so wrong. Multiple government officials from the city of Flint, Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency resigned over the mishandling of the crisis.

“It’s difficult for me to understand at any level what happened in Flint,” said Dave Johnson, a deputy manager at the Southern Nevada Water Authority. “What we have here and the systems that we have, the regulatory oversight that we have — it’s just very, very difficult and a very unfortunate circumstance.”

• • •

Water is a subject of intense testing and scrutiny in Southern Nevada, arguably more so than in other parts of the country.

What is the Safe Drinking Water Act?

It’s a federal law that was enacted in 1974 to protect public health by regulating public drinking water across the nation. The law authorizes the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to set national health-based standards to regulate drinking water to protect against contaminants, both naturally-occurring and man-made.

The original version focused mainly on water treatment to protect water quality, but amendments made in 1996 added regulations regarding source water protection and funding for water system improvements. The amendments also introduced a public information requirement. Water systems operators now must prepare annual consumer confidence reports to distribute to residents outlining detected contaminants, possible health effects and the water’s source.

Why? Not only is water scarce in our desert, it is the lifeblood of our economy. No clean water, no tourism.

“When you are safeguarding the resource for not only the 2 million residents that we have but the 40 million annual visitors, we need to make absolutely sure that our water is not only meeting the standards but is much better quality,” Johnson said.

In 2014, the Las Vegas Valley Water District, the Water Authority’s largest member utility, collected 36,000 water samples on which scientists conducted 327,000 analyses. The Water Authority also has its own research and development department that tests and monitors compounds in the water. Experts say the valley’s water testing is more extensive than in many other parts of the country.

Daniel Gerrity, a UNLV professor of environmental engineering, said the Southern Nevada Water Authority lab was one of the first to study in detail pharmaceuticals in the water supply.

“A utility doesn’t necessarily have to do that,” Gerrity said. “But they view that as being warranted to make sure that they’re ahead of all the issues.”

One of the primary functions of the Aater Authority is monitoring the valley’s water supply for harmful chemicals regulated by the EPA under the Safe Water Drinking Act, a federal law that protects public drinking water supplies throughout the nation.

A 2009 study by the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit environmental research group in Washington, D.C., ranked Las Vegas and North Las Vegas drinking water among the worst in the nation.

Las Vegas water contained 30 pollutants, including small amounts of radium, arsenic and lead; a dozen exceeded the EPA’s health guidelines. North Las Vegas water contained 11 chemicals that exceeded health guidelines set by federal and state agencies. Researchers found the drinking water had traces of 26 contaminants, including uranium.

Both then and now, Water Authority officials said the valley’s drinking water fared poorly in the survey because the agency does more robust monitoring and sampling than other municipalities and has more sensitive instruments.

“We have very sophisticated capabilities for being able to detect anything in the water,” Johnson said. “So with that, there are many, many utilities that would never be able to see or know the kinds of things that may be in the water that may show up as a result of our advanced testing.”

Should residents be afraid to drink local tap water?

“No, absolutely not,” said Lynn Thorp, national campaigns director at Clean Water Action, a national citizens’ organization working for clean, safe, affordable water.

Challenges special to our area

An atypical challenge the Southern Nevada Water Authority has faced in recent years is perchlorate contamination. The nation’s largest perchlorate concentration is in Henderson, northeast of U.S. Highway 95 and Lake Mead Parkway, at the site of the former Kerr-McGee chemical plant.

The factory produced 30,000 tons of sodium perchlorate and ammonium perchlorate each month for rocket fuel. Both chemicals dissolve in water like salt.

Perchlorate can interfere with the production of thyroid hormones. The perchlorate in Henderson leeched into groundwater, which traveled via the Las Vegas wash into Lake Mead.

The Nevada Division of Environmental Protection began overseeing cleanup of the site in 1997. Perchlorate levels have dropped from about 10 parts per billion in 2001 to 1.2 parts per billion — a barely detectable level — in 2014.

Though perchlorate is not regulated by the federal government, local water agencies track its presence in water.

“We enjoy some of the highest-quality tap water in the world,” Thorp said. “People should not, by any means, be afraid to drink it.”

Thorp agreed that more sophisticated water authorities, like Las Vegas’, might have the ability to detect compounds at smaller concentrations than smaller water systems with less sophisticated technology.

That the valley’s systems are in compliance with EPA standards is a good sign, Thorp said. While EPA regulations aren’t perfect, they’re set through a fairly detailed process that aims to protect human health while still considering cost, industry and economy and the capabilities of municipal authorities.

“It’s not like very many of our water systems have sources that are so pristine that they don’t need treatment,” Thorp said.

• • •

Months after news broke about Flint’s water crisis, it still is difficult for water officials here to say what went wrong there. What they do know is they have no intention of letting the same happen here.

“We’ve been talking a lot about water safety,” Johnson said. “One of the things you have to do, that’s required by law to do, is to protect water from the treatment plant all the way to the residence.”

Unlike in Flint, where proven systems were changed to save money, there has been substantial investment in water infrastructure and technology in the valley, both on the state and local government levels and in higher education.

“We realize it’s such a scarce resource; it’s so important to Las Vegas’s survival,” Gerrity said. “Every component of that water issue we micromanage, basically. If you’re in a place like Michigan, where there’s water everywhere — one of the largest freshwater sources right next door — you kind of overlook the water issue. It’s kind of a side note.”

How are quagga mussels affecting our water?

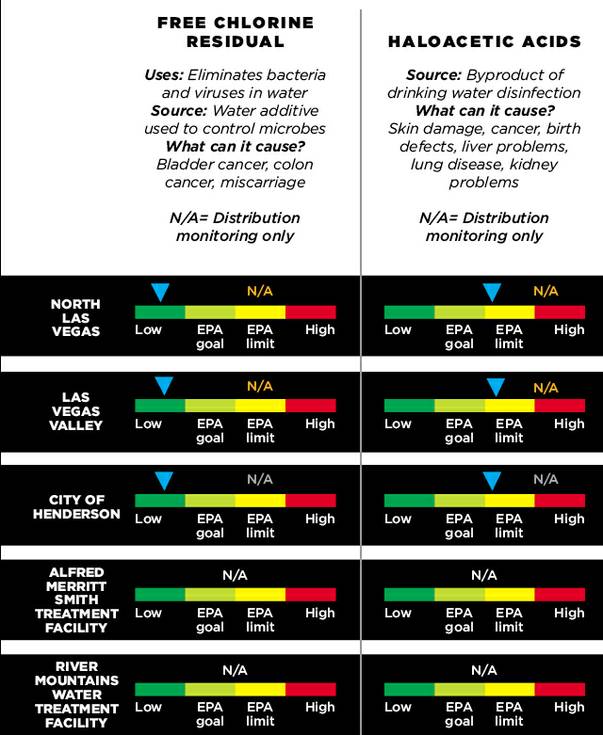

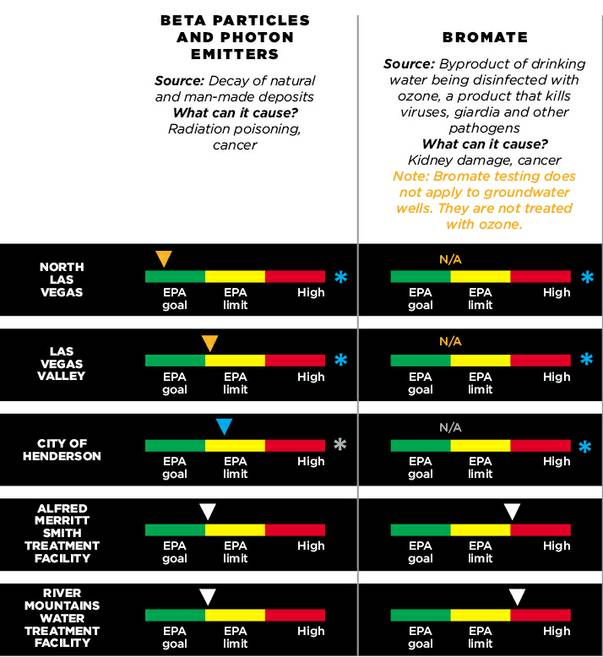

Part of the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s job is to combat invasive quagga mussels in Lake Mead. The mussels threaten the natural ecosystem and pose a threat to water infrastructure because they clog pipes and restrict water flow. The agency uses chloramine, rather than chlorine, to kill quagga mussel larvae. Chloramines are more stable and are removed during the water treatment process. Chlorine is used in the water system to preserve water quality.

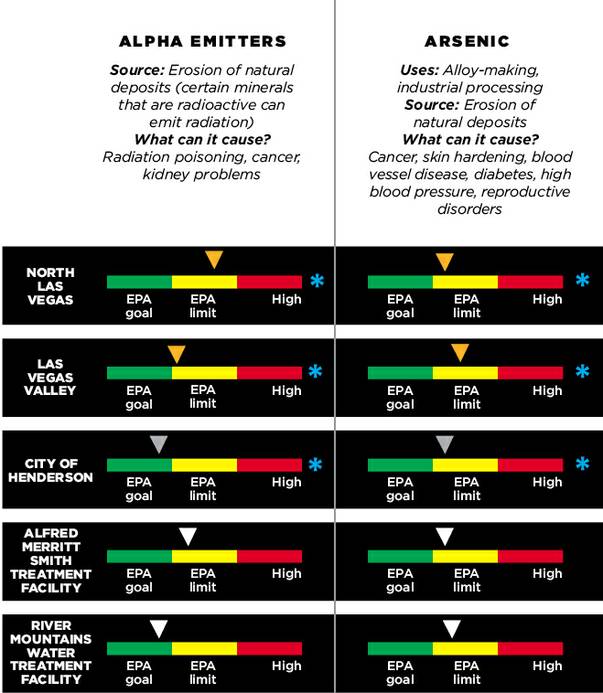

Do we have radioactive water?

There is no indication valley groundwater has been affected by nuclear testing, said JoAnn Kittrell of the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Uranium and radon are naturally occurring, she said.

The presence of uranium in drinking water typically is due to rocks that contain naturally occurring trace amounts of mildly radioactive elements. The radioactive contaminants can accumulate in drinking water sources to levels of concern.

Radon also is a naturally occurring material, related to the decay of uranium in the natural environment.

The average person will be exposed to the same amount of radiation after a year of drinking tap water as he or she would receiving an arm X-ray. Typically, the trace radioactive elements present in drinking water are too weak and too few to release enough energy to seriously affect humans.

How is water quality is tested?

Contaminants in drinking water are monitored using a mass spectrometer, which measures the mass and concentration of atoms and molecules. Mass spectrometry is used for a variety of chemical analyses across a number of fields.

The Southern Nevada Water Authority is unusual in that it has a water quality lab in-house, rather than having to send samples to a state agency for testing, said Bronson Mack, the Water Authority’s spokesman. The lab houses high-tech equipment that allows scientists to measure water quality and to develop and research new treatment techniques and protocols for new contaminants. The lab’s instruments also are more sensitive than typical devices used to measure water quality. They detect contaminants at parts per trillion rather than parts per billion. Whereas other water departments might detect no contaminants in a sample, the Southern Nevada Water Authority may be able to detect a trace amount.

Are filters effective?

Faucet and pitcher filters can be effective for removing organic material and metals from water, but the filters are used primarily to improve the taste and smell of water, not to improve its healthfulness, said Lynn Thorp, national campaigns director at Clean Water Action, a water advocacy citizens’ group.

The filters typically are packed with activated carbon granules, derived from charcoal, that trap dirt while allowing water to pass. The granules don’t remove minerals. For that reason, many filters include a layer of resins to deionize the water and remove minerals.

With any filter, maintenance is key. If the filter isn’t properly cleaned and the cartridges replaced, sediment and bacteria could accumulate, causing more harm than good.

Is bottled water better?

No. Bottled water essentially is tap water that has been treated a second time, typically through reverse osmosis, which removes minerals.

“In general, we don’t recommend bottled water,” Thorp said. “For one, it costs 6,000 times the amount, and we believe our nation’s water systems are serving up water that’s at least as clean and has other benefits.”

Water that’s the most beneficial for human health balances a good amount of nutrients with the least amount of harmful chemicals. Minerals such as potassium and magnesium give water its taste and are essential for the body, but they are eliminated during the purification process. That’s why magnesium sulfate and potassium chloride often are added to bottled water — to improve the taste and add nutrients.

Also, bottled water is not regulated by the FDA and is subject to less stringent regulations than public water systems, Thorp said.

How much radiation am I exposed to in ...

• .1 µSv* = Eating one banana

• ~1 µSv = Drinking tap water for a year

• 40 µSv = Flying from New York City to Los Angeles

• 250 µSv = Annual EPA emission limit for nuclear power plants

• 400 µSv = One mammogram

• 10,000 µSv = One full-body CT scan

• 36,000 µSv = Chain smoking for a year

• 100,000 µSv = Yearly amount linked to an increased risk of cancer

• 1,000,000 µSv = Acute dose causing temporary radiation sickness

• 10,000,000 µSv = Fatal dose; death within weeks

• 20,000,000 µSv = Fatal dose; death within days

• 50,000,000 µSv = Ten minutes next to the Chernobyl reactor during the meltdown

* µSv is a microSievert, a measurement of radiation.

How can I get involved?

You don’t have to be a scientist or water expert to become involved in protecting the valley’s most important resource. With a little research, all of us can be advocates for clean, healthy water.

1. Read your drinking water Consumer Confidence Report. Each year, you should receive in the mail a short report from your water supplier that outlines where your water comes from and what pollutants were found in it. The report also provides details about the likely source of any contaminants.

2. Review the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s “Pocket Guide to Source Water Protection” available at epa.gov. The guide provides an overview of the Source Water Assessment program and suggests steps you can take to protect source water.

3. Track down your Source Water Assessment. Each public water system should have one. The assessment provides information about where your drinking water comes from and what kinds of threats the water supply faces. To find your Source Water Assessment, visit ndep.nv.gov/bsdw/swap.htm.

4. Reach out to your community’s water officials. Call the operators of your public water system to ask questions, gather information and discuss next steps.

5. Talk with others about what you have learned. Call health care providers, conservationists, elected officials or neighbors. Ask them what they know about the community’s drinking water and if they’d like to become involved in water protection.

6. Take action. Volunteer with a water conservation organization or tackle a protection or restoration project yourself.

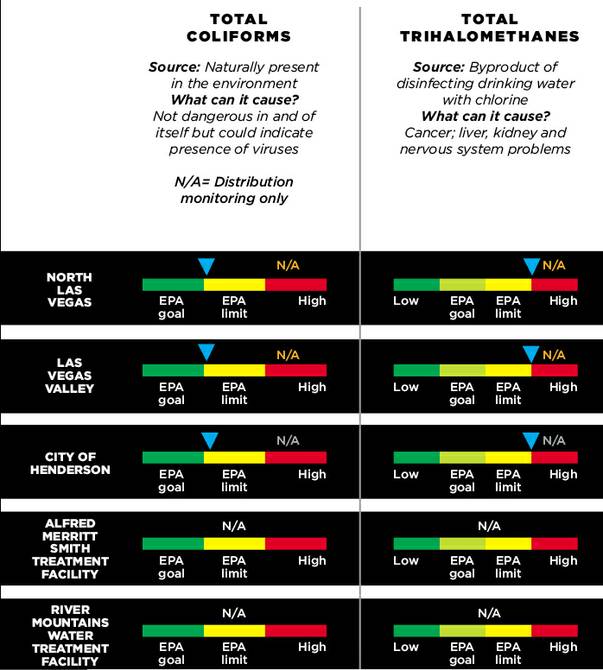

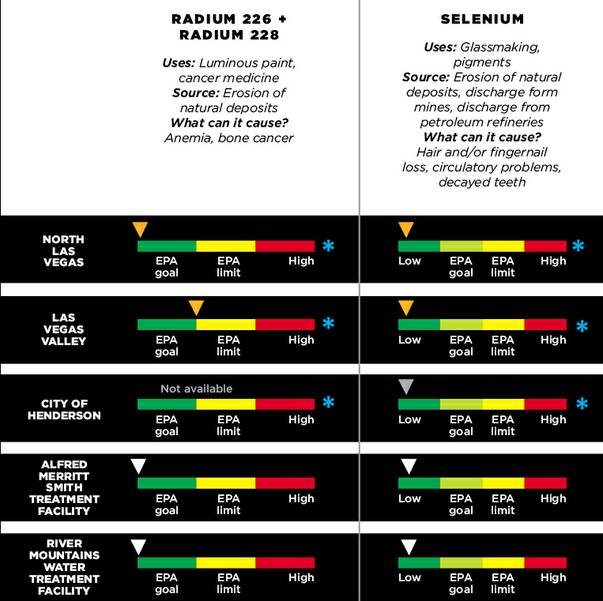

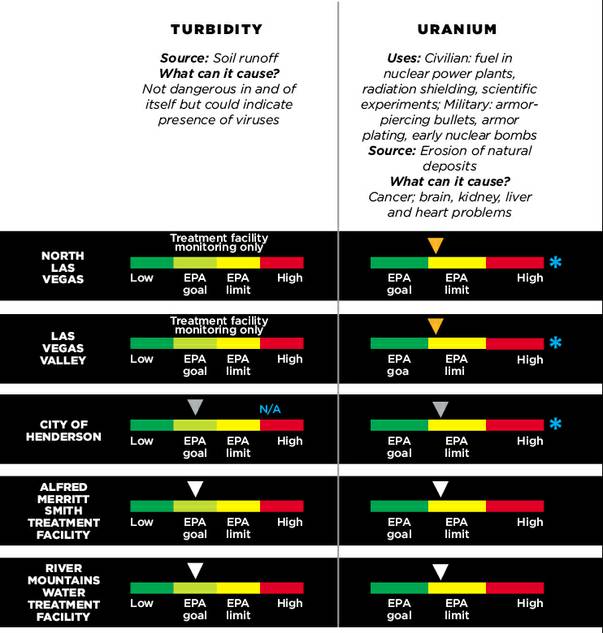

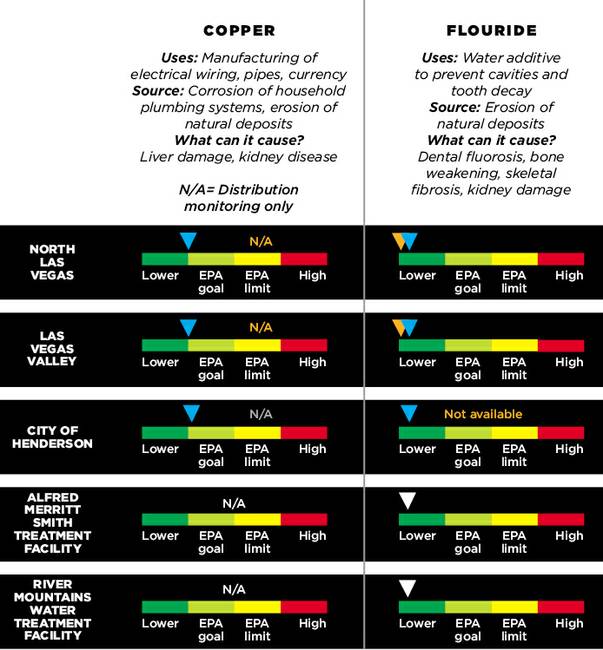

The compounds in our water

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency sets two levels for compounds regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act: a goal and a legal limit.

The goal is a non-enforceable public health ideal. It’s the maximum level at which the agency has determined there are no known or expected health risks. Most of these levels are set at zero because ideally you wouldn’t want anyone to be exposed to any amount of lead or carcinogens.

The legal limit is the enforceable standard. The EPA sets it based on how harmful a chemical is, how difficult it is to detect and how practical it is to treat. EPA officials aim to consider and balance all of the potential interests involved when setting legal limits.

The Southern Nevada Water Authority and its member utilities are in compliance with EPA regulations. Some of the average levels of some of the compounds in the valley’s water supply exceed the EPA goal, but none exceeds the legal limit. A few of the maximum levels measured exceed the legal limit, but that is considered acceptable under EPA regulations.

Ian Whitaker and Delen Goldberg contributed to this report.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy