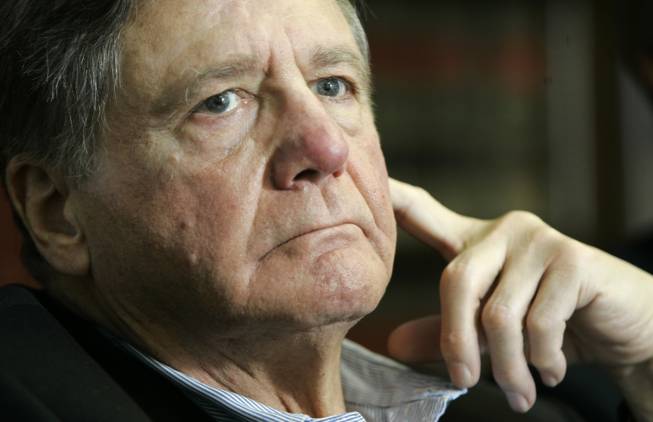

Kiichiro Sato / AP

In this Feb. 1, 2008, file photo, Jeb Magruder is interviewed by The Associated Press in Columbus, Ohio. Magruder, an aide to President Nixon who spent seven months in prison for his role in covering up the 1972 break-in at Washington’s Watergate complex, died Sunday, May 11, 2014, due to complications from a stroke. He was 79.

Friday, May 16, 2014 | 11:05 a.m.

COLUMBUS, Ohio — Jeb Stuart Magruder, a Watergate conspirator who claimed in later years to have heard President Richard Nixon order the office break-in, has died. He was 79.

Magruder died May 11 in Danbury, Connecticut, Hull Funeral Service director Jeff Hull said Friday.

Magruder, a businessman when he began working for the Republican president, later became a minister, serving in California, Ohio and Kentucky. He also served as a church fundraising consultant.

He spent seven months in prison for lying about the involvement of Nixon's re-election committee in the 1972 break-in at Washington's Watergate complex, which eventually led to the president's resignation.

In a 2008 interview, Magruder told The Associated Press he had long ago come to peace with his place in history and didn't let the occasional notoriety bother him. The interview came after he pleaded guilty to reckless operation of a motor vehicle following a 2007 car crash.

"I don't worry about Watergate, I don't worry about news articles," Magruder said. "I go to the court, I'm going to be in the paper — I know that."

Magruder, who moved to suburban Columbus in 2003, served as Nixon's deputy campaign director, an aide to Nixon's chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, and deputy communications director at the White House.

In 2003, Magruder said he was meeting with John Mitchell, the former attorney general running the Nixon re-election campaign, when he heard the president tell Mitchell over the phone to go ahead with the plan to break into the Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate office building.

Magruder previously had gone no further than saying that Mitchell approved the plan to get into the Democrats' office and bug the telephone of the party chairman, Larry O'Brien.

Magruder made his claims in a PBS documentary and an Associated Press interview.

He said he met with Mitchell on March 30, 1972, and discussed a break-in plan by G. Gordon Liddy, finance counsel at the re-election committee and a former FBI agent. Mitchell asked Magruder to call Haldeman to see "if this is really necessary."

Haldeman said it was, Magruder said, and then asked to speak to Mitchell. The two men talked, and then "the president gets on the line," Magruder said.

Magruder told the AP he knew it was Nixon "because his voice is very distinct, and you couldn't miss who was on the phone."

He said he could hear Nixon tell Mitchell, "John, ... we need to get the information on Larry O'Brien, and the only way we can do that is through Liddy's plan. And you need to do that."

Historians dismiss the notion as unlikely.

"There is just no evidence that Richard Nixon directly ordered the Watergate break-in," legal historian Stanley Kutler told the AP in 2007. "Did Magruder hear otherwise? I doubt it."

Magruder stuck to his guns in the 2008 AP interview, saying historians had it wrong.

He became a born-again Christian after Watergate, an experience he described in his 1978 biography, "From Power to Peace."

"All the earthly supports I had ever known had given way, and when I saw how flimsy they were I understood why they had never been able to make me happy," he wrote. "The missing ingredient in my life was Jesus Christ and a personal relationship with him."

He was absent from headlines in later years, although the comic strip Doonesbury featured him in a June 12, 2012 episode as two characters reminisced about attending a Jeb Magruder "concert" in 1973.

Magruder, who was born in New York City on Nov. 5, 1934, held sales and management jobs at several companies, including paper company Crown Zellerbach and Jewel Food Stores. He also became active in Republican politics, including serving as Southern California coordinator for the 1968 Nixon campaign. Bob Haldeman, Nixon's chief of staff, hired him to join the White House in 1969.

He received a master's degree in divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1981, then worked at a Presbyterian church in California. First Community Church in suburban Columbus, and First Presbyterian Church, a 200-year-old parish in Lexington, Kentucky.

But he could never fully leave the scandal behind.

In 1988, Dana Rinehart, then Columbus mayor, appointed Magruder head of a city ethics commission and charged him to lead a yearlong honesty campaign. The city was reacting to an incident in which people scrambled to scoop up money that spilled from the back of an armored car.

An ethics commission "headed by none other than (are you ready America?) Jeb Stuart Magruder," quipped Time magazine.

Magruder took it in stride, saying at the time, "it's a characteristic in American life that there is redemption."

At Dallas-based RSI-Ketchum, a church fundraising consulting group, his Watergate reputation opened doors but could also make it difficult to carry out his job because people were so eager to talk about the scandal, Jim Keith, the company's senior vice president, said in 2007.

During those years Magruder seemed to accept his role in one of the country's most famous political scandals.

"There was a long time where he ran from that stuff, but it finally got to the point where he accepted it and the celebrity that went with it," Keith said in 2007.

Magruder had new struggles in retirement.

In 2003, he pleaded no contest to disorderly conduct after police in the Columbus suburb of Grandview found him passed out on a sidewalk. In 2007, he was hospitalized after police said he crashed on a highway after hitting a motorcycle and a truck with his Audi Sedan.

Accident investigators concluded he had a stroke, and he was cited with failure to maintain an assured clear distance and failure to stop after an accident or collision.

After pleading guilty to the reduced charge of reckless operation, Magruder was fined $300, placed on one year of probation and lost his driver's license for a year. A 60-day jail sentence was suspended.

The day after the plea, Magruder said he had no memory of the crash.

"It was not a pleasant experience, but I don't remember the details of it," he said.

Despite his problems, Magruder continued to advocate doing the right thing in retirement. He told The Columbus Dispatch in 2003 that Americans should work for moral change by helping the homeless or working with Habitat for Humanity.

"Can you change everything? No," he said. "I think you do what you can do."

In his 1974 book, "An American Life: One Man's Road to Watergate," Magruder blamed his role in the scandal on ambition and losing sight of an ethical compass.

"Instead of applying our private morality to public affairs, we accepted the President's standards of political behavior, and the results were tragic for him and for us," he wrote.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy