Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2013 | 2 a.m.

Sun coverage

The job itself pays a healthy annual base salary of about $133,500, but getting there could cost candidates a couple million dollars.

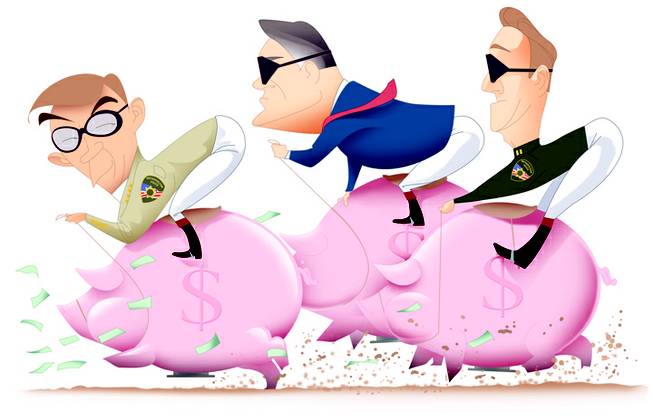

Welcome to the world of politicking for Clark County sheriff — an elected position widely regarded as the second-most influential in Nevada, behind the governor.

With the 2014 election less than a year away, a handful of candidates have emerged vying for the vacancy created by incumbent Sheriff Doug Gillespie, who is not seeking a third term. That means it’s open season on the Las Vegas Strip as sheriff candidates scramble to secure coveted big-money donations from resorts and gaming companies to bankroll their campaigns.

The upcoming election’s lineup of sheriff candidates includes, among others:

• Metro Police Capt. Larry Burns, who oversees an area command in West Las Vegas

• Former Assistant Sheriff Ted Moody, who retired from the police force in July in protest of Gillespie’s decision not to fire an officer.

• Former Las Vegas Township Constable Robert “Bobby G” Gronauer.

Assistant Sheriff Joseph Lombardo also has expressed interest in throwing his hat in the ring but, despite working with a political consultant, hasn’t made a formal announcement.

“I think any one of them in the next two, three months could catch some fire — could really move up,” said Billy Vassiliadis, CEO and principal of R&R Partners, who has managed past Clark County sheriff campaigns. “I think it’s just going to really come down to an awful lot of work. I don’t think anyone is going to overwhelmingly get the fundraising.”

But exactly how much will it cost candidates to wage competitive campaigns? Past elections provide some evidence.

When Gillespie sought election for the first time in 2006, he amassed more than $1.5 million in contributions, according to Clark County campaign expense reports.

His list of donors who contributed the maximum $10,000 allowed by state law reads like a Las Vegas travel brochure: Bellagio, Boulder Station, MGM Grand, Mirage, New York-New York, Palms, Wynn.

And that’s just naming a few of the resorts listed. There are also numerous hefty donations from gaming companies, high-profile lawyers and a smattering of Southern California-based production companies.

“The most challenging part of fundraising is getting to the big-money donors — the people who donate the maximum amount,” said Metro Officer Laurie Bisch, who ran for sheriff in 2006 and 2010.

Former candidates and political consultants expect the victorious sheriff candidate in this election to spend as much as $2 million on campaigning.

Many of those five-figure checks stem from face-to-face meetings between company executives and sheriff candidates, who give their best sales pitch and explain their platform, Vassiliadis said.

Vassiliadis served as campaign manager for John Moran in 1982 and Jerry Keller in 1994, helping steer both men to victory. He also acted as an unpaid adviser to Gillespie.

Vassiliadis’ decades-long experience has led him to make two conclusions about sheriff campaigns: Yes, money matters. But so does support from the law enforcement community — fellow officers, judges, district attorneys and other agencies.

Candidates who have strong support from the law enforcement community and a good rapport with casino security chiefs tend to rake in more of the large donations, Vassiliadis said.

“I know it has been said a thousand times, but that’s Nevada’s economy sitting on the Strip,” Vassiliadis said.

Not all successful candidates have spent the most money, though.

Gillespie’s challenger in the 2006 election — businessman Jerry Airola — spent roughly $3.8 million, largely funded by his own robust bank account. He lost anyway, which critics attributed to his lack of law enforcement experience.

Even so, Bisch said she supported a campaign-spending limit to level the playing field. Bisch spent about $75,000 on her 2010 campaign, according to campaign expense reports, but she believes $500,000 would be a fair spending limit.

“I think you could see who could do the most with the least amount of money,” said Bisch, who pulled out of the 2014 race to support Burns. “More bang for the buck.”

In lieu of a spending limit, Vassiliadis argues that state law should embrace stronger disclosure requirements, such as real-time reporting of campaign contributions.

“As long as people are aware — as long as there’s complete transparency — they can decide then if they think that some industry, some company or some individual has given too much money to any candidate,” he said.

Successful sheriff campaigns also hinge on politically savvy tactics, whether that’s reaching out to safety-conscious senior citizens or mothers worried about neighborhood violence, Vassiliadis said.

Because the sheriff election is nonpartisan, the differences among candidates tend to be more nuanced. Top contenders generally have good experience, so it comes down to how they will manage Metro on a daily and hourly basis, Vassiliadis said.

“There’s not a sexy way to say that in a 30-second TV spot,” he said.

The official filing period for sheriff candidates begins March 3. The primary election follows three months later on June 10, when the field will be narrowed to two candidates.

Vassiliadis predicts the top two sheriff candidates will become apparent before the primary based on their ability to raise money. Even more money will flow after the primary election.

“My sense is that they’re all working pretty hard right now,” he said. “They all recognize they’re in a real crowded field.”

Gronauer, the former constable turned small-business owner, said he plans a campaign fundraiser the second week of January. He’s busy talking to his network of friends in the Las Vegas Valley and seeking a political consultant who, as he says, will be “in it for me, not for them.”

He doesn’t buy the notion that successful candidates need to spend $500,000 on television ads leading up to the primary or shell out $400,000 for a campaign manager.

“You have to have people that believe in you. That’s all,” he said. “If you’re just another dollar sign to somebody, that’s difficult.”

Campaigns run on money, but Gronauer said he’s confident smart strategy can propel his campaign to victory — with or without an influx of checks from Las Vegas Boulevard.

“The resort corridor will stick with whomever the establishment is, and I’m not worried about that,” he said. “I have enough other avenues to get my money without the big hotels. Would I like to have them? Absolutely.”

But Gronauer, 66, isn’t a newcomer to this town or the election process. After a 24-year career with Metro, Gronauer was elected constable of Las Vegas Township in 1999.

“I have a whole lot of friends in this valley, and I hope to cultivate that into campaign funds,” he said.

As the mad dash for money and votes gains steam, Chris Collins, executive director of the union representing Metro Police officers, the Las Vegas Police Protective Association, hopes candidates keep in mind the large responsibility they could inherit.

“The next sheriff is going to be a very important guy,” he said. “They’re going to have to hit the ground running.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy