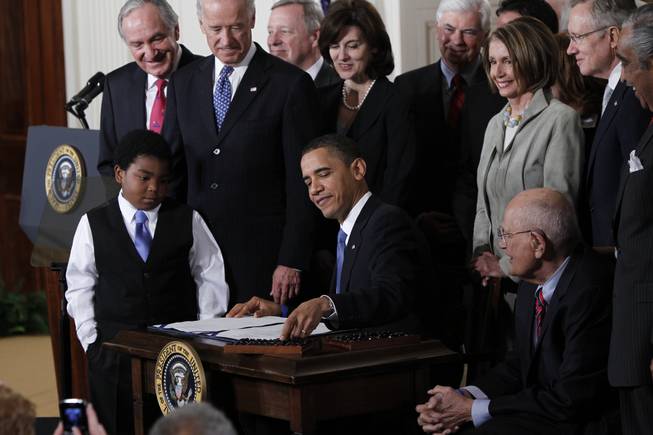

Charles Dharapak / AP

In this March 23, 2010, file photo, President Barack Obama reaches for a pen to sign the health care bill in the East Room of the White House in Washington.

Friday, Jan. 4, 2013 | 12:10 a.m.

Jan. 1, 2014, seemed far away when President Barack Obama signed his health care program into law back in 2010. That is the date as of which the law's main parts will take effect, including the mandate to buy insurance and the expansion of Medicaid.

Recent years have been rather hectic, however. Republicans hoped to gut "Obamacare," first in court and then by electing a Republican president. Obama is still in the White House, however, and — thanks to a surprise vote from Chief Justice John Roberts — Obamacare, as even the president now calls it, is still law.

Jan. 1, 2014, is still the day when its main parts must go into effect, however, so the next 12 months will be busy ones.

Even without controversy, implementation would be complex. The law tries to reform a sector that accounts for nearly one-fifth of America's GDP. Its 906 pages invite even more pages of regulation from the Department of Health and Human Services.

Implementation will be much harder than Democrats had imagined, however. Bickering has consumed precious time. HHS has delayed issuing essential regulations. Most important, many state governors remain uncooperative.

The big question is how the reality of reform will differ from the Democrats' vision of it. The huge law contains many provisions, but its main goal is to expand health insurance.

Beginning in 2014, insurers will no longer be allowed to refuse coverage to the sick. The cost of insuring them will be paid out of insurance fees from cheap, healthy consumers, which is why the law requires everyone to buy insurance or pay a penalty.

The law also seeks to extend Medicaid to all those earning as much as 138 percent of the federal poverty level, which was $15,415 for one adult in 2012. As of 2014 those with incomes of between 100 percent and 400 percent of the poverty level will qualify for subsidies on new state health exchanges, where individuals can shop for insurance.

The law's opponents had hoped that the Supreme Court would scrap all this. It did not, except for one piece: States may choose whether or not to expand Medicaid.

Some measures already have taken effect. HHS has started to reward hospitals for providing good care, rather than lots of it. Some employers are contesting the law's requirement that insurance should cover contraception, however, and the future of two main provisions, the health exchanges and the Medicaid expansion, is blurry.

The exchanges must be ready by October 2013, so that consumers can choose insurance beginning in 2014. Some states, most led by Democrats, have prepared diligently. HHS has doled out $1.8 billion to help. Many Republican governors have done nothing.

Even enthusiastic states will struggle to meet the deadline, however. HHS waited until after the election to propose important rules, such as the types of insurance that may be sold. The final regulations are still to come.

Republican governors who sat on their hands during the law's first years are now wagging their fingers at HHS for being slow. Many want nothing to do with the exchanges, anyway.

"For any state who's running an exchange, it is 'state' in name only," scoffed Gov. Scott Walker of Wisconsin in November.

Opposition to Obamacare is impeding even some Democratic governors. In Missouri voters passed a ballot measure to prevent their governor from moving forward. Democrats in Washington had hoped that each state would build its own exchange. On Dec. 17 HHS said that only 18 states had applied to do so. Of these, only five are led by Republicans.

The remaining states will have exchanges either wholly or partly run by the federal government. HHS is scurrying to prepare. A lawsuit in Oklahoma seeks to scuttle this effort, claiming that a legislative glitch prohibits subsidies on the federal exchanges. If the suit fails, as seems likely, conservatives will have achieved an odd result: The federal government will have a greater role in health care.

Medicaid is an even bigger source of uncertainty. In January state legislatures will meet for the first time since the Supreme Court ruling. They must decide whether to expand Medicaid for 2014. Obamacare promises to pay for 100 percent of costs from 2014 to 2016, inching down to 90 percent in 2020 and thereafter.

This is a good deal for states, according to scholars at the Urban Institute. An extra 21.3 million people would enroll in Medicaid by 2022. The expansion itself would require states to spend an extra $8.2 billion from 2013 to 2022, compared with an $800 billion jump in spending by the federal government. Savings from a drop in uncompensated care might even save some states money. At present the uninsured receive "free" treatment at hospital emergency rooms, with states picking up part of the bill.

States still are wary, though. Federal funding is not reliable. Obama's own budget suggested cutting the federal share of Medicaid spending. In the midst of talks about the fiscal cliff, HHS said that idea had been scrapped. Medicaid cuts may loom in the future, however.

All this uncertainty is difficult for state bureaucrats, not to mention hospitals and insurers. During negotiations for reform, hospitals accepted lower payment rates in exchange for the promise of more insured patients. If states don't expand Medicaid, this will be a bum deal. Most aggrieved, however, are the patients the law is supposed to benefit. Those with incomes below 100 percent of the poverty line will not qualify for subsidies on the exchanges. If states do not expand Medicaid, 11.5 million poor adults will be left without insurance.

The exchanges raise more questions. Will employers stop sponsoring insurance for their workers, leaving them to the exchanges? The insurance lobby says that the law's strict requirements will raise prices — for example, a limit on fees for the old will drive up fees for the young. How expensive will insurance become? HHS says that it may delay some requirements, to prevent a spike in prices, but which restrictions would it postpone? And if young consumers pay a penalty, rather than buy insurance, will prices go up for everyone else?

By this time next year, at least some of these questions will have answers.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy