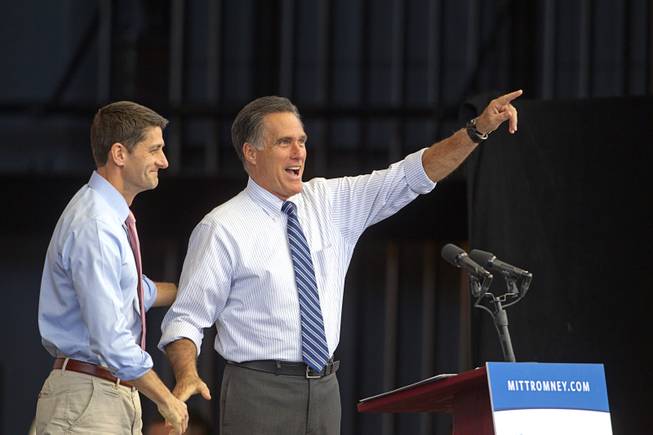

Republican vice presidential candidate Paul Ryan, left, introduces presidential candidate Mitt Romney during a campaign rally at the Henderson Pavilion Tuesday, Oct. 23, 2012.

Saturday, Oct. 27, 2012 | 2 a.m.

A small nonpartisan research center operated by professed “geeks” has found itself at the center of a rancorous $5 trillion debate between President Barack Obama and Mitt Romney.

No white paper or policy manifesto put out during the presidential campaign has proved more controversial than an August study by the Washington-based Tax Policy Center, a respected nonprofit that issues studiously detailed tax analyses.

That study found, in short, that Romney could not keep all of the promises he has made on individual tax reform, including cutting marginal tax rates by 20 percent, keeping protections for investment income, not widening the deficit and not increasing the tax burden on the poor or middle class. It concluded that Romney’s plan, on its face, would cut taxes for rich families and raise them for everyone else.

The detailed paper proved kindling for a political firestorm. Romney criticized the center as performing a “garbage-in, garbage-out” analysis, and his campaign accused it of partisan bias. The Obama campaign used the center’s numbers to argue that Romney had proposed a $5 trillion tax cut. Economists jumped on the bandwagon, too, flinging analyses back and forth and picking apart the projections and assumptions in the report.

At the Tax Policy Center, responses ranged from irritation at the partisan nature of some attacks to incredulity over the political hysteria.

“There was this résumé-hunting, White-House-visitor-log” searching feel to the response, said the center’s director, Donald Marron, a former Bush administration economist.

“That was unanticipated,” he added dryly.

In many ways, the report did just what the center was created to do: inject solid numbers into a shifty, accusatory, raucous political debate. The decade-old center — a joint project of the Brookings Institution and the Urban Institute, two nonpartisan grandes dames of the Washington world — was founded precisely to “fill that niche,” Marron said.

“A lot of tax policy discussions are — how to describe them? — people yelling at each other,” he said. “We believe that good information leads to better policy discussions and ultimately better policy outcomes.”

The center’s claim to provide reliable, nonpartisan information comes in part from its staff makeup. It has about four dozen affiliated staff members and scholars — most are economists, several are considered top experts in their fields, and a number have experience in either Republican or Democratic administrations.

It also is derived by virtue of its ownership of a highly sophisticated tax modeling system, one that took about two years to build and has a small coterie of specialists to tend it. The model resembles those used by government offices to forecast the effect of tax code changes, and it relies on about 150,000 anonymous tax returns and a wealth of data on pensions, education, consumer expenditures and economic growth.

“They’re one of the few groups that have this very big, very accurate model,” said Martin A. Sullivan, the chief economist and a contributing editor at Tax Analysts, a specialty publisher. “What they’re doing is just making the best computations available” for others to interpret.

That includes so-called distributional analyses that show how changes to the tax code would alter the relative burden on high-income and low-income families — a dry tax topic yet one of the most politically potent ones of the campaign, given the broader debate about tax fairness and inequality.

The analysis of the Romney proposal has proved highly controversial, not just among politicians, but also among some economists.

Researchers including Martin Feldstein of Harvard and Harvey S. Rosen of Princeton have argued that Romney’s tax math might work if he raised taxes on families making more than $100,000 a year — not $200,000 to $250,000 a year, as he promises — or if his plan gave a strong jolt to economic growth.

“Reasonable economists disagree on” the growth effects of plans like Romney’s, said Alan J. Auerbach, a tax expert at the University of California, Berkeley, who added that he did not see the math working out as currently described. “It matters a lot what kind of reductions you’re making or how you’re paying for tax cuts.”

Others have argued that the Tax Policy Center filled in too many of the holes in Romney’s light-on-detail proposal — making a full analysis impossible and skewing the results of the center’s paper.

“It is not an analysis of Gov. Romney’s plan,” said Scott A. Hodge, the president of the Tax Foundation, a nonprofit research group also based in Washington. “It has been, I think, mislabeled as such and misinterpreted as such. We don’t think there are enough details to analyze.”

He said he believes it is possible to devise a distributionally neutral, revenue-neutral tax reform that cuts rates in the way Romney has described.

The Tax Policy Center said it sought as many details as possible from the Romney campaign. (Its economists said it has a cordial back-and-forth with the economic policy teams in both campaigns, as it did in 2008.) Given the numbers available, it tried to perform the analysis in the most generous way possible and still did not see how Romney’s rate cuts could square with his other goals.

“We wrote a technical, accurate paper given the available information,” said William G. Gale of the Brookings Institution, one of the paper’s main authors. “The criticism that you can’t analyze the Romney tax plan because there isn’t one? That hasn’t stopped other economists from analyzing its growth effects. I like to have substantive discussions about tax policy. The uproar about the paper has not been substantive.”

Many economists across the political spectrum have said they found the report’s conclusions convincing, like Alan D. Viard, a tax expert at the right-of-center American Enterprise Institute.

Sullivan said: “I like tax reform. I want to broaden the base. It’s something I’ve devoted my life to. And I welcome Gov. Romney and the Republicans’ strong push, but the plan doesn’t work out. It’s not mathematically possible.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy