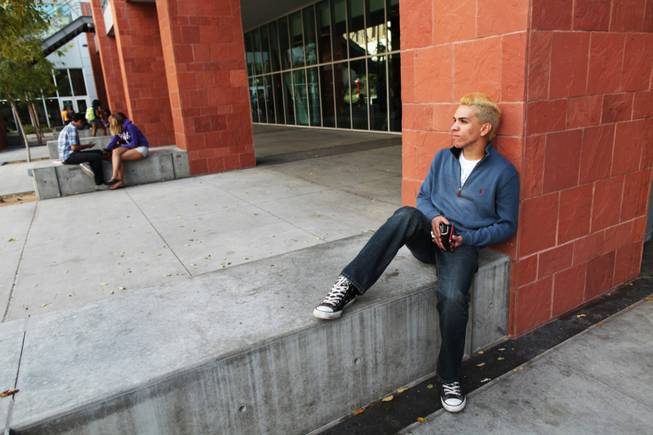

Rafael Lopez, 23, is a psychology major at UNLV who has applied for a work permit through deferred action, the federal program that allows some young immigrants who are residing in the country illegally to temporarily avoid deportation, Tuesday, Oct. 23, 2012.

Wednesday, Oct. 24, 2012 | 2 a.m.

Sun coverage

UNLV student Rafael Lopez, like thousands of young immigrants around the country, is old enough to drink alcohol but is eagerly anticipating a moment that most people experience halfway through high school: the chance to get a driver’s license.

Lopez, a 23-year-old psychology major, is one of nearly 180,000 applicants nationwide for deferred action, the federal program announced earlier this year that allows some immigrants without a legal residency status to obtain a work permit.

His application is in, his fingerprints have been taken, and now, while he waits, he affords himself some time to think of all of the doors the permit will open.

“Obviously, I want to get my license,” Lopez said. “I have been dreaming of the moment when I can have an actual ID and have a Social Security card. There are people who joke with me all the time: ‘Are you sure you want a Social Security card? Are you sure you want to pay all those taxes?’ I will pay as much taxes as the government wants as long I can stay. First thing is get my Social Security card, then get a license, then I’ll apply for a job.”

On Monday, Lopez saw firsthand the relief that awaits.

Alan Aleman, a 19-year-old College of Southern Nevada student, applied for deferred action on Aug. 15, the first day the government started accepting applications. Monday afternoon, he visited the office of Hermandad Mexicana, a nonprofit organization that provides immigration services where Lopez volunteers, to show off the work permit he received in the mail that morning.

Aleman, as far as activists and immigration attorneys in Las Vegas know, is the first in Southern Nevada to receive his permit. Before deferred action, Aleman was careful not to expose his status.

“Getting that card in my hand made it real,” Aleman said. “It’s hard to believe until you actually have the proof. I think it was cool for the others to see that it’s actually happening, too. Someone actually got their permit. The first thing I did was go to the Social Security office to get my number, and then I went to Hermandad to show everyone.”

Aleman, whose sister also entered the country illegally and is applying for a permit, said he wanted to join the Air Force and pursue a career in medicine.

Aleman was smart to get his application in early; the volume of submissions increases the wait for Lopez and others who delayed even a few weeks to apply.

In the first month of the program, more than 82,000 applications were received and 29 permits were granted, according to United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, which is administering the program. As of Oct. 10, 179,794 applications had been submitted and 4,591 had been approved. Some organizations have estimated that as many as 1.7 million people are eligible, 30,000 of them in Nevada.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, as the program is officially known, was announced June 15 by President Barack Obama. The program defers deportation or other immigration proceedings for a period of two years, does not offer an official legal residency status and provides accepted applicants with a work permit, not a visa.

Department of Homeland Security officials have said the wait time for application responses is expected to slow in the coming months.

Lopez is used to long waits, and stops and starts.

His parents brought him into the country illegally when he was 1 year old. He grew up aware of his status, warned to be careful and avoid detection.

In 2005, Lopez said, an unscrupulous immigration attorney approached his father’s employer about “legalizing” his staff of construction workers. Lopez’s father volunteered. However, Lopez said the lawyer scammed his father and the employer and filed asylum paperwork for the workers even though they were not eligible. Instead of receiving a legal residency status, the entire family, except for Lopez’s U.S. citizen younger sister, got a deportation order.

By that point, Lopez was a sophomore in Valley High School’s International Baccalaureate program. His parents, neither of whom graduated from high school, refused to give up on their children’s best chance for an education. In 2008, his parents were out of work and the entire family collected recycling and scrap metal to make ends meet. Lopez has left UNLV for semesters at a time so he could attend the College of Southern Nevada for less money.

“My thinking process is in English,” Lopez said. “If I’m going to be in school in an academic environment in Mexico, my Spanish would not be sufficient. I wouldn’t be able to write in a manner that my professors would understand. I wouldn’t be able to get very far. It’s also different culturally. At home, we eat Mexican food and watch Spanish-language TV, all that stuff, but it’s different. I’ve been here my whole life, and they are going to have different attitudes.”

Lopez said he wanted to go on to study immigration law at UNLV, a subject close to his experience. Even those who have job skills that should travel well have said that returning to their country of birth after entire childhoods spent in the United States is not as easy as it sounds.

Carlos Martinez was one of the first 30 people to receive a work permit under deferred action. The Tucson, Ariz., resident has a bachelor’s degree in computer science and a master’s degree in systems engineering from the University of Arizona. He received numerous academic awards and paid his way through college with private scholarships. Yet, when he looked for work in Mexico, he was rejected.

“I have family members in Mexico who told me, ‘Carlos, you are so smart. You can get any job in Mexico,” Martinez said. “I decided to throw my resume out there to Mexican companies, and no one called back. One guy asked me how I paid for college if I was undocumented, like he was accusing me of something or didn’t believe me. I told him I got private scholarships. I just didn’t feel welcome. God had a plan for me to stay here.”

At 30 years old, Martinez, who is now applying for jobs at Google, IBM and other tech companies, just barely slipped in under the deferred action age limit.

To qualify, applicants must have been under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012; arrived in the United States before age 16; and lived here for at least five years. They must attend school or have served in the military and cannot have criminal records or pose a threat to national security.

Las Vegas immigration attorney Peter Ashman said some young immigrants’ families avoided government agencies when they first arrived in the country, thus making it difficult to gather the necessary paperwork to prove continuous residency. Other cases are complicated by criminal histories that straddle the line of what is considered serious enough to warrant disqualification.

“Every one of the cases is as different as a snowflake,” Ashman said.

Local agencies also have had to adjust to the new program as applicants have been making document requests to meet the deferred action program's stipulations for continuous residency in the country. The Clark County School District said it has received a well-above-normal number of requests for transcripts since deferred action was announced. In August 2011, the district received 309 transcript requests; this year, the figure was 1,111. While the district has not added staff to deal with the extra requests, district spokeswoman Penny Ramos-Bennet said the standard wait for a records request has now doubled from five days to 10 days.

Deferred action has its critics. GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney and Republicans have called the program an election-year maneuver by Obama designed to win support from Hispanic voters, who overwhelmingly support the Dream Act. Romney said the problem of immigration reform deserves a permanent solution, a common criticism of deferred action. In August, 10 Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents sued Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano and ICE Director John Morton, arguing deferred action forces them to break the law when they willfully ignore deportable detainees.

Romney has stated he would not rescind work permits that already have been granted if he wins on Nov. 6, however, he indicated he would not allow the program to continue. That has left some of those who are eligible to continue their wait.

“I have cousins who are waiting to apply until after the election,” Lopez said. “They are so scared, and I get it. It’s not that easy to come out to the world and say, ‘I’m undocumented.’ It’s their future, and they are afraid that they will be taken away from their families and friends, your community and city and country you love. You are putting yourself at risk of losing everything you’ve done, your education. You could be deported. We’re going to have a big wave after the election. We’ll have a huge, massive wave of people if Obama wins.”

Lopez and the other applicants for the work permits are thankful for the opportunity to emerge from their marginalized existences, however temporary. Most of them have mixed families, where some are citizens or legal residents and others still hope for an immigration reform that offers permanent solutions for all.

“That’s the issue. ... This is not the end. This is just temporary, and our goal is to get a green card,” Lopez said. “Our goal is to get citizenship because we want to remain permanently. We don’t want to live with uncertainty. Until we remove that, the fight isn’t over. Even after the Dream Act, my fight for my parents will continue.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy