Special to the Las Vegas Sun

People look out their broken hotel room windows while they wait for help during the MGM Grand Nov. 21, 1980, fire.

Wednesday, Nov. 21, 2012 | 2 a.m.

Editor's Note: In remembrance of today's 32nd anniversary of the MGM Grand fire, the Sun arranged a gathering of a group of firefighters who were there to tell their personal stories, most of which have never been presented publicly until now. Members of the group included some of the first to arrive at the scene, where 85 people died and some 700 were injured. The firefighters, who have all retired from the Clark County Fire Department, also provided the Sun with many photos taken during the investigation — images which have also never been published.

Sun coverage

Related stories

MGM Grand 1980 Firefighters

On Nov. 7, 2012, seven firefighters came together for the first time to talk about what happened during the Nov. 21, 1980 MGM Grand fire.

MGM Grand 1980 Fire Footage

Footage of the Nov. 21, 1980 MGM Grand fire shows the fire in progress while rescue crews and firefighters attempt to put it out and save guest.

Two distant, black columns of smoke caught John Pappageorge’s eye as he drove to work on a crisp, 38-degree morning in November 1980.

Pappageorge, then a deputy chief with the Clark County Fire Department, wondered if the smoke might be coming from a pile of tires on fire. Or was it a building?

Before he could make a call on his two-way radio to find out, a voice from Fire Control crackled over the speakers.

“We have a report of a fire in a building in The Deli of the MGM, entrance No. 2. That’s entrance No. 2 to the MGM for The Deli.”

Within seconds, Pappageorge heard the first firefighters reporting in over the radio.

Crews from Fire Station 11 didn’t have far to go. They were on the north side of Flamingo Road, right across the street from the MGM Grand Hotel — now Bally’s — one of the largest resorts on the Strip at the time.

Pappageorge stepped on the gas as he headed to the 26-story high-rise at Las Vegas Boulevard and Flamingo Road. The smoke columns were growing larger.

“You’ve got a problem,” he told himself.

But he had no idea what that day was about to bring — the second-deadliest hotel fire in U.S. history.

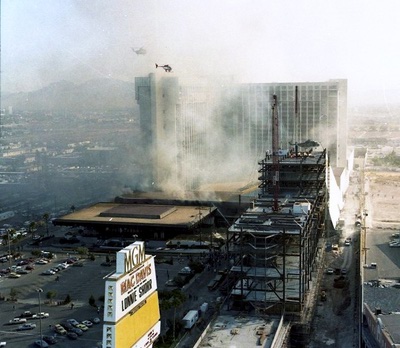

When it was over, the Nov. 21, 1980, fire killed 85 people and injured nearly 700 more. It could have been worse — there were 4,000 to 5,000 people in the building, including 3,400 guests.

The tragedy became a wake-up call that eventually spurred new safety codes and regulations for high-rise buildings that were adopted nationwide.

But on the day of the blaze, the resort resembled a war zone. Helicopters swirled through heavy smoke, plucking victims from the roof. Firefighters swarmed – 550 in all, from 28 engine companies, eight ladder companies and 15 rescue units. Body after body was pulled from the building, so many that the refrigerated morgue at the Coroner's Office couldn't hold them. A refrigerated truck was brought in, and the 84 people who died that day were placed there in body bags. The 85th victim died weeks later at a hospital in Houston, said Scott Browar, who was an assistant coroner.

Despite the passage of 32 years, the sights and sounds of the day remain scorched in the collective memories of the firefighters who were there.

"I absolutely believe what they did way back then was heroic," Pappageorge said. "The fact that they went in and got so many people out was unbelievable ... God knows how many more would have died if they hadn't have done that job. They are absolutely heroes."

First a spark, then a fireball

Sometime in the early morning hours, before The Deli opened, an electrical wire began sparking behind a wall of the restaurant.

How long it went unnoticed is not known, said Lorne Lomprey, who was then a captain and fire investigator. Lomprey would be on the scene for the next nine days trying to piece together what caused what he called the “monster fire.”

The monster first revealed itself after 7 a.m., when flames broke out of the wall and into a waitresses’ service station at The Deli.

A kitchen worker who had just arrived for work had a chance to put out the fire with a hose. But as he sprayed the flames, he was warned by another Deli worker not to put water on the electrical fire.

The blaze grew quickly, devouring everything in its path inside the ground-floor restaurant — wall coverings, cabinets, chairs and dining booths. At that point, the kitchen staff and the security guards were the only ones aware of the danger, because no customers were seated. As the fire grew out of control, the security staff called the fire department at 7:16 a.m. And a public address operator in the security office downstairs was instructed to make an announcement to evacuate the casino.

The operator made the announcement twice for emphasis, prompting those in the casino to grab their chips, cash and belongings and run to the exits. Casino operators and others working below the gaming floor described the noise above them sounding like a "herd of elephants." The operators were told to leave.

But high above the casino floor, those in the hotel tower had no idea the mayhem that was unfolding. In the confusion, no alarm was manually sounded to warn guests in the tower.

By 7:18 a.m., two minutes after the call came in to Station 11, Bert Sweeney and a few other firefighters from the station arrived at the MGM Grand and entered the hotel from the Flamingo Road entrance.

Sweeney, now 66, remembers getting 40 or 50 feet inside. “That’s when we saw the finger of smoke coming out of The Deli,” he said.

The smoke was drifting across the casino, above the slot machines and the pit area for blackjack, roulette and craps.

Sweeney saw people running away from the smoke to the west exit on the Las Vegas Boulevard side of the building, but there were still some people on the casino floor.

Then, Sweeney said, “we saw the fireball come out of The Deli. ... It bounced once off the casino floor at the very end of the casino and went up, and I think it hit the ceiling.”

The firefighters realized the light gear they were carrying wasn’t enough, so they raced back to their engine to grab heavy water lines. Right behind them, a wave of fire, heat and smoke blasted out of the building.

Sweeney looked at his helmet. The heat had melted part of his face visor into a clump of plastic. Looking through the doors, firefighters could see an inferno of swirling flames.

Back into the belly of the fire

Carrying heavy, 2 1/2-inch water lines, the firefighters fought their way back into the burning casino.

As they worked their way inside, Sweeney felt glops of something falling on him from above. The tiles and adhesive on the ceiling were melting.

“It was kind of a weird sensation. It was melting like gum,” Sweeney said.

About that time, Pappageorge arrived at the west entrance along the Strip. The fire had blown out the doors, and the porte cochere — the outdoor canopy over the valet area — was on fire.

He was the only one there. The other firefighters were staged along Flamingo Road. They didn’t even realize the fire had spread that far through the casino, Pappageorge said.

As Pappageorge joined the command area set up along Flamingo, Jerry Bendorf, then a 35-year-old rookie fire captain, was stunned by the scene in front of him as he arrived. The pressure from the casino fireball had gone into the sewer and blown the covers off the manholes on Flamingo Road, causing smoke to pour from the openings. Flames consuming the valet canopy had spread to the line of empty vehicles underneath it.

“It was amazing because there were cars that had been left there for valet parking and they were already on fire,” Bendorf said.

Then came, perhaps, the most terrifying sight.

As debris rained down from above — shards of window glass — Bendorf looked up. Frightened hotel guests, waving and yelling for help, were on their balconies and leaning out of smashed windows as smoke poured through the tower.

Firefighters shouted back, urging people not to jump.

Meanwhile, as Sweeney and his group attacked the fire on the north end, it continued to rage for at least another half-hour on the west side until firefighters knocked down most of the flames and started going inside. That's about the time Bill Lowe, then a 37-year-old engineer paramedic from Station 14, entered from the front entrance to help put out the remaining smaller fires scattered about the casino floor.

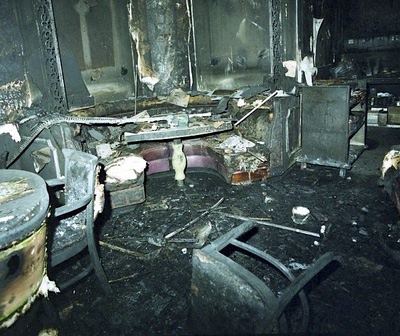

“It was unbelievable to walk in and see a whole casino charred,” Lowe said. “Every once in a while, you’d see something recognizable, like a slot machine or a table. But everything was just charred, like a big flash over.”

There were bodies all around. Eighteen people were found dead in the casino. City firefighters, who also responded, “had pointed out and said they’d found a cocktail waitress who was burned and to just make sure you didn’t step on her,” Lowe said.

Before Lowe had arrived, Skip Miller, who had made his way to the roof of the casino, beneath the south tower, said people from above were breaking windows with furniture.

“We were having tables and chairs coming out the windows down on us, not to mention all the glass,” Miller said. “We were lucky and were able to dodge it.”

Some of the people on lower floors who were trapped by smoke started tying bed sheets together to try to crawl down their balconies.

Disaster on the upper floors

According to separate reports by the National Fire Protection Association and the Clark County Fire Department, firefighters confined the blaze to the casino level in a little more than an hour. But while the fire was being contained, the worst part of the tragedy had already been playing out in the hotel's T-shaped tower. The tower had been drawing up the black smoke like a chimney, sending deadly fumes into the hallways of thousands of guests who were just waking up.

Because of the layout of the hotel, the smoke found multiple openings in the towers — stairways, seismic joints, elevator shafts and air-handling systems. It flowed mostly into the area of the hotel's T intersection, where the north and south towers met, reports said.

Also following open shafts and pipe conduits that weren't properly sealed, the smoke was flowing out of the building from the southeast intersection of the T at the 24th floor.

Because no alarms were sounded, most guests didn’t realize what was happening until they heard or saw fire engines, smelled smoke or heard people yelling and knocking on doors.

Many guests in lower levels managed to get downstairs when they realized the hotel was on fire, coming outside to find firefighters and emergency medical personnel waiting to help them. Some were ushered onto school buses that took them to the Las Vegas Convention Center.

Miller remembers that so many people were rushing down the south stairs that he and another firefighter had trouble going up around them to reach the casino roof. Most of the guests were orderly — the smoke hadn't reached the south stairs. However, on the high floors, some were turned back by the smoke and sought refuge in their rooms. Many broke windows to signal rescuers and get fresh air.

Lomprey — the former fire captain and fire investigator — said that while the fire was still burning in the casino, he and a Metro Police officer went up several flights of stairs in the north tower of the hotel.

Near the elevators, they found six people in the hallway who had died, overcome by toxic fumes. Lomprey realized it was probably carbon monoxide and that he was breathing it.

“I looked at the police officer and he looked at me. I said, ‘We don’t belong here,’” Lomprey said.

They got out quickly, wondering how many more people had died.

John Jersey, then a 33-year-old firefighter paramedic, and his partner, Jim Perkins, methodically combed for survivors through the north tower, carrying only a few bottles of air. Room by room, they pounded on doors, kicking them in if they weren't answered and making sure they got people out. They helped hundreds. Despite the smoke and eventually running out of air, neither of them remembered thinking about the danger to themselves. There were too many people needing help, and the two firefighters had a job to do. They would take out one group and go back for more.

"You just kick into a mode and do what you were trained to do. There is no thought about what is going on outside the fire," Jersey said.

Perkins also remembered being focused more on getting the survivors out more than on his own safety as they searched room by room for trapped guests: "I think it definitely makes you appreciate life a lot more and appreciate how fragile it is."

They saw just how fragile when they ran into heavier smoke accumulating in hallways around the 14th floor.

“From 16 on up, it was a disaster zone,” Jersey said. “We were actually tripping on bodies in the hallway. We would check them for a pulse and move on. We would leave them and try to find somebody alive.”

Jersey hadn’t seen so many bodies since he was a Green Beret reconnaissance specialist in Vietnam. He and Perkins found bodies in rooms, in halls, in the elevator lobby. They were on beds, in corners of their rooms and in bathtubs. Some had their faces covered with towels.

“I think we tagged about 42 people altogether,” said Perkins, who also says he is still haunted by the memories.

“When we hit a floor, we would go through and search every room on that floor, get everybody who was ambulatory who could walk into a safe room, and then we would try to tag the people, the fatalities,” Perkins said.

The difference for survival seemed to be whether guests had broken out the windows or opened their hallway doors. If they opened their doors, smoke would come in from the hallways. If they opened windows, smoke might come in from the floors below — or be blown in by the rotors of the large Air Force helicopters landing on the roof.

“The ones that kept doors shut and had stuffed towels under doors (and into room vents), they were OK,” Perkins said.

On each floor, Perkins and Jersey would find a room with fresh air -- a safe room -- and take the survivors there.

To search, the two would crawl below the layer of smoke on one side of the hallway and knock loudly on each door. If no one opened it, they would kick it in. Once in the room, they would search in the bathrooms, under the beds and in the closets. Then they would go to the other side of the hallway and do the same thing in each room. It took 30 to 45 minutes per floor, Jersey said.

At one point, they needed something to use to write on the bodies -- to record what time the victims were found and the names of the firefighters who found them. They hunted around and found a tube of lipstick. When they would complete a search of a floor, they would take everyone who was waiting in the safe room up to the roof as a group, carrying those who needed help.

One floor in particular still brings back disturbing memories for Perkins, who was then 31 years old.

“We saw a big pile of people with their arms wrapped around each other in front of the elevator,” he said. "There were probably 10 to 12 people who had died in each other’s arms. It’s something I’ve had nightmares about ever since.”

Perkins remembers going into one room and finding the bodies of two people who had succumbed to the toxic smoke and fumes.

“And the very next room, there were two couples who were sitting at the coffee table drinking tequila and partying,” he said, remembering the ironic scene on a grim day.

Most of the survivors could walk, but Perkins and Jersey had to carry many people. Jersey was only 5-foot-9, but he could carry a 200-pound person at the time over his shoulders. He would use a fireman's carry, grabbing the person's ankle and wrist and draping them over his shoulders. Jersey remembers also using a rope to help carry people on his back. He and Perkins would loop the rope around the person's legs, and both firefighters would carry the person up the staircase to the roof above the 23rd floor.

Once on the roof, the survivors were evacuated by helicopter. The Air Force dispatched a heavy-lift helicopter and other choppers that evacuated 300 people from the roof and another dozen trapped on balconies. The firefighters would then go down to the next floor and get another group.

"We were pretty spent by the end of the day. Stopping and breaks were a luxury you didn't have," Jersey said.

Jerry Bendorf, the rookie fire captain, and the other two firefighters, meanwhile, were also searching the north tower.

“The higher we got, the heavier the smoke was,” Bendorf said. “I was actually crawling on my hands and knees and feeling the walls. I could actually feel I was crawling over bodies.”

Investigators said many guests panicked and left their rooms. The doors would shut and lock behind them. If they didn’t take a key, they were trapped in the smoke-filled hallways.

In some rooms, Bendorf found that victims had managed to scribble messages to loved ones on the mirror before taking their last breath. After so many years, Bendorf can't remember the exact wording of any of the messages, only that they were personal.

Firefighter Bert Sweeney, also in the north tower, rescued a group of deaf tourists, after a tour bus driver said they were still in their rooms. They could not hear the firefighters knocking on the doors, so rescuers had to go back and kick in the doors to clear the rooms.

“They were OK. It was just the idea that in doing the quick shot and moving on to cover as much ground as possible, we overlooked a busload of deaf people,” Sweeney said.

At the end of the day, firefighters recovered 61 bodies from the north tower: 25 in hotel rooms, 22 in the corridors, nine in stairways and five in elevators. One woman died when she either jumped or fell.

Firefighter Skip Miller remembers carrying out about 10 bodies. He put them on gurneys and took them to the roof, where they were loaded onto helicopters and taken to the county morgue.

“Every now and then, one would slide off the gurney. And it would be total silence because we had to put them back on,” Miller said. “And the worst part about it was they looked like they were just sleeping because there was no trauma. That’s what made it pretty sad.”

The toll on firefighters

As Jersey and the other firefighters combed the building, they often removed their air packs and let the victims breathe through them. Finally, they just ran out of air and threw their tanks aside. Without the tanks, they were forced to crawl under the layers of smoke in the hallways.

Bendorf remembers keeping his face pressed to the carpet on the floor. It was tough, choking work. He would stick his head out a window if he got a chance and try to get fresh air. As he did so, people on balconies would call out for help. The ordeal would affect him later — both physically and emotionally.

Bendorf said one of the chiefs ordered him to get out of the smoke and go to the paramedics. Bendorf said he didn't realize how bad he was. But when the paramedics checked him, they found he was suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning. He spent three days in the hospital.

“I was pretty much out of it,” he said. “I do remember when I got to the hospital, it was around noon, I think. I remember [news of the fire] was on the TV in my room. And I had them shut it off. I just didn’t want to see it.”

Elsewhere at the scene, Jersey was ordered by one of the chiefs to get into an ambulance. Jersey insisted to the chief that he was OK, but now says he must have been in a daze. The next thing he clearly remembers from the fire was being at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center surrounded by doctors. They told him his carbon monoxide level was “through the charts.”

“They couldn’t believe I was conscious,” Jersey said. “I was two points below lethal. If he wouldn’t have ordered me in, no telling what would have occurred.”

Jersey was kept in the hospital on oxygen for four days. He was among 35 firefighters who were admitted to hospitals, most suffering smoke inhalation.

Retired fire inspector Royce Leonard, now 68, drove a group of the firefighters who had been separated from their various groups back to their home stations in a fire truck.

"When I was taking the guys home, taking them back to their station, we were driving down the Strip. And every time we stopped, people were congratulating us," Leonard said. "That stuck out, probably more than anything."

Though greeted as heroes, the firefighters were physically and emotionally exhausted. Some simply couldn’t cope with what they had seen.

“We are firefighters, and we have to go on,” said Pappageorge, now 72. “But some of the guys quit. They left town.”

Pappageorge said he was kept extremely busy at the scene, talking to members of the news media and working with logistics. He stayed businesslike through most of the day. But then something hit him as he dealt with the grisly task of organizing the information about the body count. As he was reading through a long list of names of the deceased, he just had to stop.

"I was just so overcome," he said.

But there was no let-up. The fire investigation continued for the next month, and Pappageorge's heavy workload continued. He said he didn't know if staying busy might have helped him get through it.

"That's a question for the psychiatrists, not me," he said. "I can understand some guys wanting to stay and some guys wanting to leave. You just have to pull yourself together. ... It certainly bothered me about as much as anybody else."

Skip Miller said he remembers going out with other firefighters for a beer after they left the scene.

“We were all in shock,” Miller said. “We didn’t say too much. We had dinner. Then we all went home.”

Jim Perkins said he “definitely had nightmares about what we’d seen up there. I think it changed me a lot.”

Besides making it realize how fragile life can be, it also made him want to learn more about fire rescue. Perkins said he went on to become heavily involved in the technical side of rescue. He said it also made him realize he could have used more counseling after the fire.

"Emergency workers need to be able to have some peer support and maybe some professional counseling," he said. "I think it would have made a lot of difference in the lives of everybody who was there."

Jersey, the firefighter who crept through the hotel side-by-side with Perkins that day, said he finds it hard to return to the restored building.

"It's very eerie in the hallways," he said. "Some things still stay with you."

Bendorf said he found himself having trouble talking about the fire.

Afterward, he was assigned to Fire Station 11 — just across from the MGM Grand. Seeing the blackened interior and drapes blowing through broken windows reminded him each day of his ordeal. He started withdrawing from others. When firefighters from other cities dropped by and wanted to talk to the captain about the fire, Bendorf couldn’t do it.

He continued working. But the memories kept haunting him. He also helped fight an arson fire that killed eight people three months later at the Hilton Hotel. Bendorf said he was trapped in a stairway and thought he was going to die during that fire. He spent three more days in a hospital for that one.

But the close calls with death were building up. His last day of work was in 1995, after going out on a call when some rioters began burning buildings on Las Vegas' west side. When crews arrived, police told them to be careful because rioters were shooting at firefighters. After that, Bendorf just couldn't do it anymore.

"I kind of broke down and said I can't go back to work," he said. He went to see a doctor, who diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder. The doctor recommended retirement.

For several years, Bendorf had trouble seeing other firefighters, but he eventually began meeting with his friends from the department again.

Now, he said, he has no trouble talking about the fire. He has even written up his memories of the fire to hand down to his grandchildren.

“I came to the conclusion I did the best I could do,” Bendorf said.

The aftermath and recovery

In the end, investigators traced the source of the fire to faulty wiring in the kitchen. And because most of the fatalities were caused by the way the fire and smoke spread so quickly, county and state lawmakers retooled fire safety and building codes from top to bottom.

Hotel operators were required to install sprinklers everywhere in their buildings — there were none in The Deli kitchen at the MGM Grand. New codes made sure barriers would keep smoke from spreading from floor to floor.

Today, county fire and building inspectors say Las Vegas’ resorts are among the safest, if not the safest, in the world.

After the fire, MGM restored the hotel, which sustained about $50 million damage. On July 30, 1981, the hotel reopened — this time with a $5 million fire safety system that exceeded the new fire safety codes in place.

Less than two weeks later, the new system would be put to a real-life test, according to the book “The Day the MGM Grand Hotel Burned,” by Deirdre Coakley with Hank Greenspun, Gary C. Gerard and the staff of the Las Vegas Sun.

“When sparks from a welder’s torch caused insulation material to smolder, automatic alarms went off in rooms on two upper floors and guests were told via the public-address system to remain in their rooms and tune in to a closed-circuit TV channel for instructions,” the book said. “The incident was minor, there was no evacuation, and the new fire-safety system worked exactly as it was meant to do.”

As for the men who fought the fire, seven of them came together for a reunion recently to talk about their memories from that day. For most, it was the first time they had talked to each other about what they had seen and done that day. The reunion was cathartic for some, but overwhelming for one.

Up to that point, Bert Sweeney, described by his friends as a “Godzilla” for his physical strength as a young man, had no trouble talking about the fire. But after listening to his fellow firefighters tell their stories, he fell silent.

When it was his turn to talk, his voice cracked and he drooped his head, unable to continue.

He apologized. But he had no reason to.

Every man in the room had been there before.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy