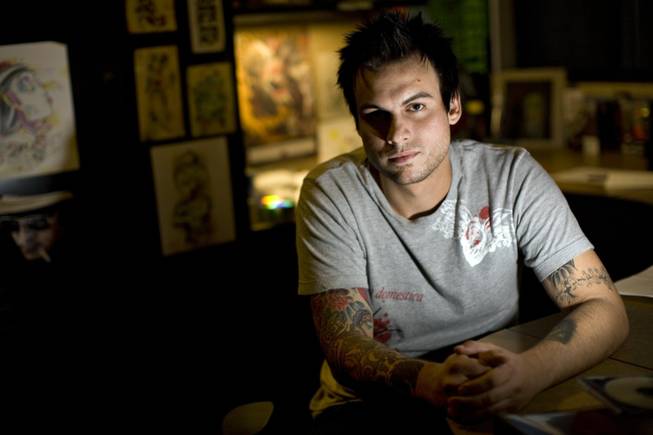

Eric Jones, 24, who graduated two years ago from The Art Institute of Las Vegas, will likely be paying on his student loans until 2032. Jones, a graphic artist, says he would have considered less expensive college options had he known the eventual cost of his payments.

Tuesday, June 5, 2012 | 2 a.m.

Sun coverage

- A shift in the future of higher education funding (04-06-2012)

- Letter to the readers: Exploring ways to fund higher education (03-30-2012)

- Proposed funding formula for Nevada colleges puts focus on degrees earned (03-02-2012)

- Suggested early changes to higher ed funding formula are greeted warmly (01-20-2012)

- More Sun education news

Nevada Attorney General Catherine Cortez Masto has joined 21 of her counterparts in asking Congress to limit the ability of for-profit colleges to enrich themselves at taxpayers’ expense by going after veterans and the lucrative benefits of the GI Bill.

The bid is the latest chapter in a nationwide campaign to better police private colleges that seek to turn a profit by offering higher education to those who don’t — or usually can’t — attend public universities.

Over the past few years, national officials have become convinced that the quality of the education at such institutions takes a backseat to financial interest, turning these purveyors of degrees into predatory, double-talking recruiters, who offer sub-par services.

As a result, the colleges are turning out graduates who are far less competitive in the job market than those coming from private and public nonprofit institutions, according to academic and government investigations.

And much of it is free from state regulation — particularly in Nevada.

As the state’s top prosecutor voices support for the federal campaign, it highlights where Nevada’s efforts to regulate the for-profit college industry are succeeding and where they’re lagging behind.

A Sun examination of the spotty federal data available on for-profit colleges operating in Nevada indicates students from some of the largest for-profit colleges have a loan default rate more than four times that of students from Nevada’s universities.

Nevada also hasn’t sought to address the problem through legislation the way other states have, the Sun has found.

“There are three parts to overseeing the for-profit schools,” said Stephen Burd, a senior analyst for Education Sector, a nonpartisan think tank. “States license the schools and oversee them, creditors weigh in on their quality, and then the federal government is the gatekeeper to the federal aid programs. The problem is that none of the parts have done a very good job. Even though it looks on paper like there’s a lot of regulation, it’s not very effective and none of the players are very good at it.”

Nevada is a microcosm of the national picture. As a state with a large military population, increasingly dismal employment opportunities in failing blue-collar sectors and few public university options, Nevada is now host to a plethora of for-profit institutions.

Nationally, veterans have been at the forefront of the crusade to curb bad practices.

Last month, President Barack Obama issued an executive order requiring colleges enrolling veterans to disclose more information about the cost of the degree and prospects for gainful employment after graduation. The order also limits the access for-profit college recruiters could have to military bases.

Both the House and the Senate are working legislation to cap the amount of GI Bill funding for-profit colleges are allowed to accept under law — the same changes sought by the attorneys general.

But the federal government sees for-profit colleges as posing a much broader problem.

In report after report, academics and government investigators have sounded an alarm that degrees from for-profit institutions provide a significantly less valuable education and produce graduates far less competitive in the job market than their public and private nonprofit counterparts.

The Department of Education is already implementing regulations that take effect next month to make for-profit colleges comply with “gainful employment” standards or risk losing federal funding.

But even if some for-profit institutions fall short of the standard, that doesn’t mean they’ll stop operating in Nevada.

“We don’t make any distinction between profit and nonprofit, if it’s a privately owned university that is,” said Tim Breen of the Nevada Commission on Postsecondary Education, the body that licenses institutions of higher learning. “It’s the same procedures, the same application, the same state law for either profit or nonprofit.”

According to a congressional report, more than half of all students enrolling in the largest for-profit institutions are dropping out before completing their degree, and those who do finish aren’t necessarily able to pay back their loans.

While for-profit universities enroll only 12 percent of the nation’s college students, they account for 26 percent of all student loans and 46 percent of all student loan defaults.

That puts considerable pressure on taxpayers.

Right now, Congress is deadlocked over how to make sure college students aren’t pushed into default because of ponderous compound interest on their students loans. In July, the federal student loan rate of 3.4 percent is expected to double absent some deal in Washington.

But student debt and taxpayer burden translates into hard cash for for-profit institutions. According to the Department of Education, “more than a quarter of for-profit institutions receive 80 percent of their revenue from taxpayer-financed federal student aid.”

Just because state governments can’t threaten to withhold funding doesn’t mean they are impotent when it comes to regulating for-profit institutions.

In North Carolina, the state legislature created a special board last year to oversee the for-profit college industry. In California, the state legislature passed a bill to withhold state financial aid from schools that break default rate ceilings. In Maryland and Oregon, only students at public and private nonprofit colleges are eligible for state financial aid.

In Nevada, schools — for-profit or not — are required to refund tuition if they don’t provide the full training paid for by the student and must hold bonds to protect students financially if the college goes under. The National Consumer Law Center recently praised Nevada for being one of only six states to take such steps.

But the Silver State has no measures similar to other states to tighten regulations on for-profit schools.

“For-profit institutions are still regulated by the states, but it varies by state, how much they keep track of them,” said David Deming, an associate professor of education and economics at Harvard and the author of a study on for-profit institutions. “But in an environment where state budgets are very tight and get declining funding for public universities, if they aren’t going to be able to serve all students, someone has to step in.

Deming noted for-profit colleges still play an important role, “particularly for students who got a GED. This might be the only type of four-year college they can go to.

“People focus on the predatory practices, but that’s not every school. That’s just some schools,” Deming said. “You want to get incentives right and try to curb the abuses that are going on but not throw the baby out with the bathwater. But that’s easier said than done.”

Because of the lack of data, it’s hard to prove which for-profit institutions do well by their students and which act as institutional predators. It’s only in the last year that the Department of Education has begun compiling default and dropout statistics for individual for-profit institutions eligible for Title IV federal funding.

Even federal lists appear to be spotty. The federal government lists only 10 proprietary schools in Nevada. The University of Phoenix, DeVry University, Morrisson University and the Art Institute of Las Vegas — all well documented as for-profit institutions that are to receive federal student aid — are missing from that list.

Among those on the list are two associate’s degree-granting institutions, Kaplan College and Everest College.

Kaplan’s numbers are getting better. Its rate of students defaulting on their loans dropped to 17 percent in 2009 from 21 percent in 2007. But Everest’s are getting worse: 23 percent defaulted in 2009, compared with just 16 percent in 2007.

By contrast, the default rate at Truckee Meadows Community College and the College of Southern Nevada is 13 percent. Four-year colleges UNLV and UNR are 4.5 percent and 3.9 percent, respectively.

Representatives at Nevada’s for-profit colleges either did not answer requests for comment or deferred questions to the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities.

“Unfortunately, it appears some elected officials are more concerned with repeating regurgitated attacks against private sector colleges and universities than looking at critical facts concerning our sector of higher education,” association President and CEO Steve Gunderson said in a statement. “Each state controls its licensure of schools, which allows attorneys general to take appropriate action against individual institutions as opposed to maligning an entire industry.”

But even as federal regulators try to take on for-profit institutions, enrollment has started to slip. Since the start of the recession, for-profit college enrollment has shrunk by 40 percent.

In Nevada, there’s no clear trend.

Since 2007, enrollment at the University of Phoenix — the largest for-profit college — has dropped by half. But enrollment at the local DeVry and Kaplan College campuses has grown sixfold, according to statistics maintained by the Commission on Postsecondary Education.

“The regulations are causing them to have to change the way they operate to some extent,” Burd said. “I think that’s been the major factor in why enrollments have dropped.”

But instead of recoiling from bad press, for-profit institutions are diversifying, moving away from the professional-certification programs that the government is trying to police better and toward four-year degrees.

According to Deming, that “is where the demand is.”

“You’re seeing the for-profits moving more into the B.A. market, which is also harder to regulate,” he said. “That’s also four years of Title IV money versus one or two.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy