Sun Archives

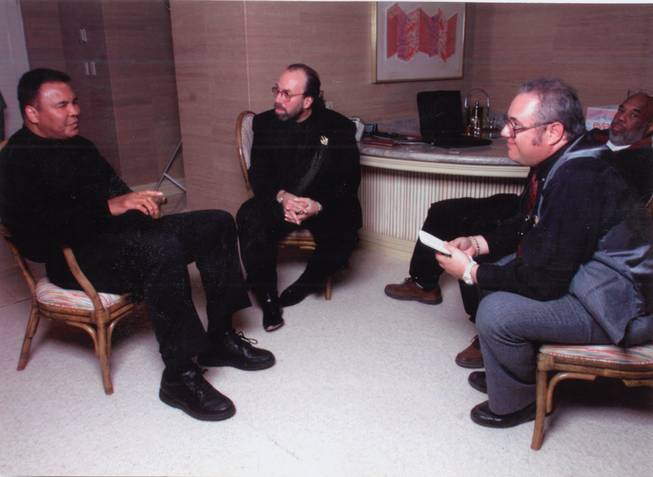

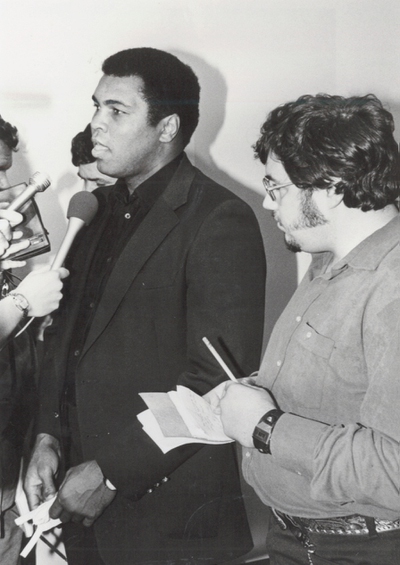

In a photo from November 2000, Muhammad Ali, left, discusses the making of a second biographical motion picture about his career, with actor Will Smith starring as the former three-time world champion. Also pictured in Ali’s suite at the Mirage are, from left, longtime Ali confidant Bernie Yuman, former Sun reporter Ed Koch and Ali photographer Howard Bingham.

Tuesday, Feb. 14, 2012 | 2 a.m.

Related stories

- Lou Ruvo Center's world-class services are for locals, too

- Volunteering at the Ruvo Center: How to lend a hand — and a heart

- Vegas gala to celebrate Muhammad Ali's 70th birthday, benefit Ruvo Center

- Lou Ruvo Center helps those afflicted by diseases of memory, mood and movement

- ‘Power of Love’ Muhammad Ali celebration to be broadcast on ABC, ESPN2

Moments before the start of the Dec. 29, 1980, Nevada Athletic Commission hearing to revoke Muhammad Ali’s boxing license, the legendary fighter told me: “Ain’t this something — one bad day on the job and they want to fire me.”

For Ali, then 38, it indeed had been a bad day — make that night. On Oct. 2, 1980, then-world heavyweight champion Larry Holmes pummeled Ali and ended Ali’s dream of winning a record fourth world title. Ali was so overmatched that regulators believed for his own health he shouldn’t be allowed to fight again.

I interviewed Ali about a half-dozen times between 1980 and 2000. Away from the TV cameras, Ali was a soft-spoken gentleman who could be downright philosophical — nothing like the loudmouth showman the public saw during his long and illustrious career.

Don’t get me wrong. Ali truly did think he was pretty — and he was, from his handsome face and his sleek physique (in his prime) to his surprisingly delicate hands.

And what an ego. I really believe he got a thrill shifting into Ali mode, trash-talking rivals and performing outrageously every time a microphone was stuck in his face or a camera was rolling.

But Ali proved time and again he could back up the taunts and raves, including his rhyming predictions of the rounds when he would defeat his foes.

But on the day the Athletic Commission “fired” Ali, boxing’s best salesman was subdued and accepting of his fate. After hours of damning testimony, Ali and his lawyers cut a deal.

Ali would give up his Nevada license, and the Nevada Athletic Commission would not oppose Ali getting a license to fight elsewhere. The deal paved the way for Ali to fight the late Trevor Berbick on Dec. 11, 1981, in the Bahamas. Ali lost that fight, too.

But Ali got to go out on his own terms. It meant vindication for Ali, which was important to the sport’s only three-time world heavyweight champion.

Striving for vindication was a thread that ran through Ali’s life, whether he was battling racial prejudice or those who damned him for being a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War.

On Saturday, Ali will be honored not only for his athletic exploits but his commitment to principles when he returns to Las Vegas for the Keep Memory Alive Power of Love Gala, a celebration of his 70th birthday. The event also will serve as a fundraiser for the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health and the Muhammad Ali Center, a cultural and education complex in Ali’s hometown of Louisville, Ky.

•••

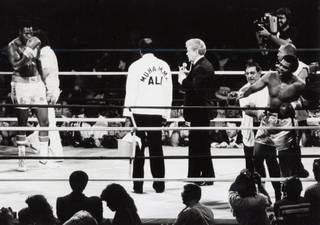

In this Oct. 1, 1975, file photo, heavyweight boxer Joe Frazier grimaces after Muhammad Ali, left, landed a blow to Frazier's head during their boxing bout in Manila, the Philippines. Ali won the fight after Frazier's manager stopped the fight in the 14th round. Frazier, the former heavyweight champion who handed Ali his first defeat yet had to live forever in his shadow, has died after a brief final fight with liver cancer. He was 67. The family issued a release confirming the boxer's death on Monday night, Nov. 7, 2011.

In 1980, I was the 23-year-old, wet-behind-the-ears sports editor of The Valley Times in North Las Vegas. Ali had retired — or so he claimed — from boxing nearly two years earlier after beating Leon Spinks in a rematch. It seemed unlikely that our paths would cross.

Earlier that year, my limited body of work as a boxing writer had been deemed good enough for me to be invited to join the Boxing Writers Association of America — one of the youngest reporters ever to get that honor.

In those days, a Las Vegas boxing writer could get a lot of experience really fast. There were weekly club boxing cards at the Silver Slipper; monthly cards at the Sahara, Showboat and Hacienda; and at least two major world championship cards each month at such venues as Caesars Palace, the Dunes and the Hilton.

But despite satisfying my appetite to cover as many boxing matches as I could, I longed to interview the greatest name in that sport, or, for that matter, any sport — Muhammad Ali.

Then rumors of an Ali comeback started circulating. I was among those columnists fueling the speculation, hoping to get an opportunity to cover an Ali fight just like my idols in boxing journalism — Nat Fleischer, Ed Schuyler, the Sun’s Mike Marley and others — had.

In the late summer of 1980, as promoter Don King was putting together the deal to pit the undefeated champ Holmes against Ali, the Nevada Athletic Commission, led by its new chairman, Sig Rogich, demanded that Ali pass an extensive physical in Las Vegas.

Despite statements from former Ali ring physician Ferdie Pacheco that Ali had kidney damage and from a London doctor that Ali had brain damage, Rogich, a longtime ad executive and political mover and shaker, said he believed Ali could pass a physical.

“I’m of the opinion he is in good physical shape,” Rogich told me in a 1980 interview. “You can’t be an athlete like that all your life and not maintain some physical adeptness. I think he’ll have it.”

But in the next breath, Rogich noted that because Ali had not fought in 22 months he should be checked out thoroughly. In short, if Ali was seriously injured or killed in the Holmes fight, the commission was going to be covered.

Ali did not completely trust the Nevada Athletic Commission. He still had a bitter taste in his mouth over losing a close 15-round decision in the first Spinks fight in Las Vegas, on Feb. 15, 1978, at the hands of Nevada commission-appointed judges.

So it was arranged for Ali to go to Rochester, Minn., to the Mayo Clinic to undergo tests to prove he was healthy.

One of Ali’s handlers, Gene Kilroy, a longtime Las Vegas casino executive, gave reports on Ali’s progress. After results from the final tests came in, Gene said, “Would you like to talk to Muhammad and get it straight from him?”

“Sure, that would be nice,” I said calmly. Inside my head, however, I was saying, “Yahoo! I don’t believe it!” Twenty-two months earlier, I was cutting cold cuts for sandwiches in my parents’ New Hampshire sub shop, and now I was about to report the historic words of a 20th century icon.

Kilroy handed the phone to Ali, who was relaxing in his suite at the Kahler Grand Hotel in Rochester, reading reports from his many tests, among them a brain scan and urine and blood samples.

“A staff of seven of the world’s best doctors gave me the green light today, and that proved all the liars wrong,” Ali told me, noting that he had been suspicious that the findings of Las Vegas doctors might be more political than medical.

Ali told me that he had trimmed down to 233 pounds and planned to lose even more weight so that on Oct. 2, the world would see not the old man Ali, but the Ali of old, dancing for 15 rounds and earning a forth reign as champion.

It turned out to be my first-ever banner story.

On July 31, the commission accepted the Mayo’s findings and the fight was on.

•••

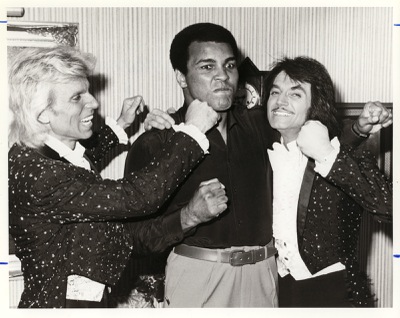

Controversial and whimsical, flamboyant and powerful, few legends encapsulate Old Vegas like headliners Siegfried and Roy. Here, during a photo-op in October 1980, the pair throw faux punches at boxing icon Muhammad Ali; all of whom have been represented by Bernie Yuman. The Greatest and magicians of a past era, joking around like kids. Now this is Old Vegas.

Muhammad Ali stepped off a flight at McCarran International Airport at 10:23 a.m. on Sept. 9, 1980. He had dropped to 229 pounds and looked healthy.

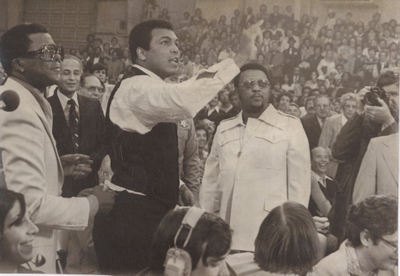

Ali checked into Caesars Palace just before noon and by 1 p.m. was in his familiar white trunks with the black stripe, dancing in the ring before several hundred spectators who had paid $3 apiece to watch him work out.

Surprisingly, only a handful of reporters were on hand for Ali’s first Las Vegas training session. Out-of-town press was not scheduled to arrive until the weekend. I knew this would be my opportunity to talk to Ali alone.

Midway through an uncharacteristically quiet workout, Ali warned doubting spectators not to waste their money betting on Holmes because Ali was going to shock the world again and win the fight.

“Holmes will run out of gas, and I’ll kick his ass! Get your tickets now!” he said.

I truly believed that Ali truly believed he was going to win — though I doubted anyone could beat Holmes at that point. Then again, in 1964, few people thought Ali — then known as Cassius Clay — could beat the seemingly unstoppable Sonny Liston. But Ali knocked out Liston in seven rounds on Feb. 25 in Miami to win his first world title at age 22.

After the workout, Ali invited me to his locker room, where we both watched Holmes work out. Ali gave me my second one-on-one interview with him.

“He (Holmes) is too old to do this — I’m older than he is, but he’s the one who is too old, not me,” Ali said as Holmes sparred, concentrating on delivering hard body punches.

Referring to his interactions with the spectators during his workout, Ali said, “I didn’t plan on talking to them at all — I needed my wind. But I had to get used to it. I’m going to talk to Larry Holmes throughout the whole fight. But I won’t psyche him out. I’ll knock him out — maybe in eight rounds, maybe in nine, but no more than that.”

Asked if the Holmes fight would be his last, Ali said, “You never know what I’m going to do next. I might retire, then come back in a year or two and fight again.”

•••

Ali tipped the scales at 217 1/2 pounds at the official weigh-in. Several of us in the press corps shook our heads over what would turn out to be a serious blunder by Ali.

In his efforts to look like the Ali of his prime, he had lost too much weight and, in effect, was dried out. (The night of the fight, Ali couldn’t break a sweat, and thus he could not cool down as the fight wore on.)

Ali’s vanity — his tremendous ego — had gotten the better of him. He was more determined to look trim to impress his legion of fans rather than to be in better fighting shape at 224 pounds with a little fat to burn during the bout.

Meanwhile, Holmes, who played second fiddle to the entertainer Ali for months leading up to the bout, let out his pent-up aggression. Ali was so badly beaten he could not come out for the 11th round. (I had predicted in my column that morning a Holmes victory in the 10th round by technical knockout.)

Days after the fight, Ali said he was “physically unfit” to fight Holmes because he had accidentally taken an overdose of thyroid medicine that made him too weak.

An after-fight urine test showed opiates in Ali’s system. His physician, Dr. Charles Bennett, said he gave Ali a painkiller and sedative after the fight and before the commission doctors could get a urine sample from Ali.

The positive drug test and the poor performance led to the commission’s hearing, which was intended to put Ali out to pasture.

•••

On Sept. 21, 1981, Ali’s longtime confidant and handler Bernie Yuman invited me to lunch with him and Ali at Caesars Café Roma. It was less than two months before Ali’s final boxing match.

After the meal, Ali turned philosophical. He stuck a finger into a glass of orange juice and let a single drop fall onto his plate.

“One of the teachings of Islam is that you go into the ocean and dip your finger in — the drop on your finger is your life and the whole ocean is what comes after that,” Ali said. “I am going to die someday. But right now I live in a million-dollar house that seven white men owned before me. I drive expensive cars. But I’ve got to look into my future. There has got to be more to life than this.”

•••

Nineteen years would pass before I would interview Ali again, this time at his suite at the Mirage.

His once marvelous athletic body had been devastated by Parkinson’s disease. His face was puffy, and he talked in a hushed, mumbled voice that at times was almost impossible to understand. But he was fully cognizant of what was going on around him. Before the interview, in front of Ali, Yuman warned me that Ali suffered from narcolepsy, which caused him to nod off during conversations, and that I might have to get real close to Ali to hear his voice as he faded into slumber.

While answering my first question, Ali started to slowly pass out and I leaned in to hear his answer. All of a sudden, Ali “awoke” and made a roaring sound that startled me and knocked me out of my chair.

I got up from the floor and looked around to see Yuman; Ali’s photographer, Howard Bingham; and Ali laughing heartily over the prank they had just pulled.

Ali had pulled the stunt on dozens of reporters, including the late Ed Bradley of “60 Minutes.”

Ali told me a second biographical film about his life was in the works, starring Will Smith as Ali, which I led with in my front-page story the following day.

After the interview, I showed Ali a scrapbook I had kept of the articles and columns I had written about him over the years. He jokingly asked if he could have it. I told him I could never replace the copies of the stories I had written so long ago.

As he handed the scrapbook back to me, Ali asked for my notepad and pen. On a blank page, he wrote, “To Ed, from Muhammad Ali 2000.”

“Here, put this in your book,” he said.

That was the last time I saw Ali, although I did interview him once more by phone in December of 2001, when the film “Ali” was released. He was about to turn 60.

Ali told me the message of the film was, “Work hard and believe and you will be vindicated.”

I recalled what Ali had told me during our lunch at Caesars Palace two decades earlier. I was happy for him because, at long last, Ali had his vindication. He was at peace because he also had found something “more to life.”

Ed Koch is a former longtime Sun reporter.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy