Teacher Mary Felber troubleshoots a problem with a robot with sophomore Sarah Kane at Mojave High School Monday, Jan. 30, 2012. Senior Marco Garcia is at right.

Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Personal touch and attention to detail helping Mojave move beyond troubled past (11-26-2011)

- Mojave students, parents embracing school’s new direction (10-02-2011)

- The Turnaround: Mojave High School (8-31-2011)

- Mojave High School’s turnaround starts with pride (8-31-2011)

- Principal Antonio Rael: To succeed, help from community a must (8-31-2011)

- Science, technology set students up for future (8-31-2011)

- Principal David Wilson: Laying down the law to change the culture (8-29-2011)

- Five struggling schools embark on a journey to improve education (8-28-2011)

Map of Mojave

This is another in a yearlong series of stories tracking Clark County School District’s efforts to turn around five failing schools.

In a nondescript room on the second floor of Mojave High School, three students are tinkering away on a dream.

For now, the dream consists only of a metal frame, six rubber wheels, and a few motors and wires. But by April, these students — dedicated members of the school’s inaugural robotics club — plan to have a fully operational, remote-controlled robot, complete with pneumatic arms and pinchers.

While robotics classes and clubs are common among some of the top-performing magnet schools in the valley, it’s a rare sight at this “turnaround” high school, located in the industrial outskirts of North Las Vegas.

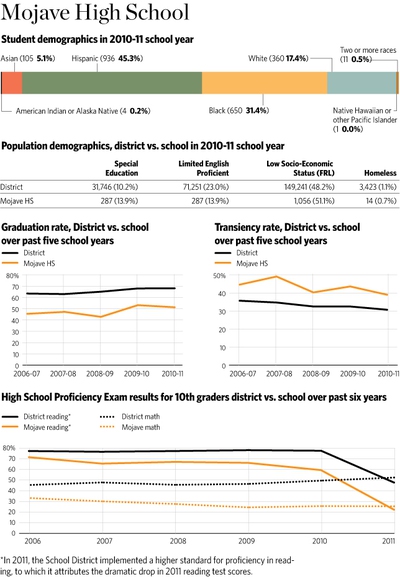

Beset by years of low test scores and abysmal graduation rates, Mojave underwent a massive overhaul this school year as part of the Clark County School District’s ambitious plan to improve student achievement.

As part of the “turnaround” — which saw the replacement of the principal and majority of the staff — Mojave executed a new academic focus on science and engineering. The cornerstone of this new emphasis is the school’s new robotics class and after-school club, said Natalie Burgess, the assistant principal overseeing the revamped science curriculum.

“Sometimes, kids don’t see how what they learn (in school) applies to the real world,” she said. “Robotics exposes the kids to math and engineering in a very hands-on, very trial-and-error way. It forces kids to problem solve in a way they can’t get from just reading a textbook.”

The fledgling robotics program at Mojave has plenty of room for growth. The robotics class — an elective that meets every day — has just 23 students, and the club has about a dozen members, some more active than others. But it’s a start, said science teacher Mary Felber, who started teaching robotics at Mojave in the fall.

•••

Conveying advanced math and engineering concepts to students at an at-risk school doesn’t faze Felber, who has a doctorate in microbiology from New York University.

“I don’t see low-performing students,” she said with a determined look on her face. “I only see students with difficulties in math. But with the right teaching, that’ll change.”

Education became Felber’s calling after her bout with breast cancer. In 1995, Felber — then in her late 20s — discovered a tumor in her left breast. After months of chemotherapy and radiation treatments that left her unable to give birth, Felber elected to have a double mastectomy.

At the time, Felber and her then-husband had been trying to have children. The cancer diagnosis not only broke up Felber’s marriage but her plans of motherhood, a dream she’s since she was a young girl, she said. The prognosis devastated her, but Felber was adamant it would not keep her down.

“Cancer was the best thing that could have happened to me,” she said. Her cancer has been in remission for three years. “Everything changes when you don’t know if you’ll be around tomorrow.”

Felber started teaching two years ago at Valley High School, but she was laid off in the spring amid multimillion-dollar budget cuts to the School District. She then applied for the challenging position of teaching science classes at Mojave, which has the lowest test scores among Clark County public schools.

Before dawn breaks every school day, Felber can be found in her classroom, setting up for her biology, science and robotics classes. Most days, the wiry but energetic teacher spends four to five hours after school helping her students build robots.

“I’m dedicated. I’m not here for the paycheck,” she said, smiling. “I’m getting my moms out.”

•••

Felber’s efforts are starting to pay off. Mojave’s robotics team placed 15th out of more than 40 teams during its first major challenge: a district-wide robotics competition last weekend in which robots had to push bowling balls and lift crates. The team is now preparing for the regional First Robotics Competition in April, where robots must throw basketballs into nets and balance themselves on a shifting platform.

Mojave’s rookie team is a “big-time underdog” in the upcoming competition, which attracts professional engineers and college students, Felber said. Even among valley high schools, Mojave is outmatched, with fewer resources and equipment than the more affluent magnet schools with robotics teams.

(Some schools have built up relationships through the years with machine shops and engineers. These schools are able to order custom parts for robots and bring in experts to talk with students, Felber said.)

Mojave has invested about $12,000 in equipment and software for its robotics classes and team so far. In addition, Felber has spent about $3,000 of her own money and donated hundreds of hours to kick-start the program.

Still, the computers in Felber’s classes are outdated. There’s not enough memory in the large desktop computers to run the latest design and robotics software. Without that, students are essentially building robots without a blueprint, Felber said.

The school doesn’t have steady revenue to guarantee funding the robotics program, Felber added. Equipment breaks or gets stolen, costing hundreds of dollars to repair or replace. Entrance fees and travel expenses for competitions can rack up. The April competition alone costs $4,000 to enter, she said.

Preparing students for competition is a major challenge, Felber said. After years of low expectations, some Mojave students struggle with the advanced math and computer coding skills necessary to construct and operate a robot, she said. Nearly half of Felber’s students were pulled out of the 35-member robotics class this semester to prepare for their proficiency exams.

Other students who come from disadvantaged backgrounds face their own obstacles, Felber said. Some students ride the bus to and from school while their parents work multiple jobs to make ends meet. There is no late bus that can ferry these students home from after-school activities — like the robotics club.

Nevertheless, Felber and school officials are hopeful Mojave’s new robotics program will spur interest in high-demand fields such as science and engineering. Next year, Mojave plans to offer a more advanced robotics course to complement the beginner level course being taught this year, Burgess said.

In addition to helping students learn skills helpful for high-technology fields, these courses can help Mojave recruit more students to the under-enrolled school, Burgess said. Currently, more than 1,000 students zoned for Mojave are attending other schools, taking with them per-pupil funding that can help Mojave offer more courses and engaging curricula. Mojave’s poor reputation might explain the student exodus, but perhaps it’s because Mojave didn’t offer a science- and engineering-focused curriculum before, Burgess said.

“We want those kids back,” she said. “We’re really trying to build this (program). It’s a good learning experience for students.”

•••

Mojave senior Marco Garcia, 17, is one of the dedicated members of his school’s new robotics club. The lanky teenager started tinkering with robots when he was 8 years old, taking apart toys and putting them back together. Now, Garcia is fluent in two computing languages and is helping to build a new robot to represent Mojave in the next competition.

“It’s a little hobby of mine,” Garcia said of his computer coding. “I want to learn as much as I can before I graduate. It’s sad I can only do this for one year.”

Garcia hopes to become a mechanical engineer someday and design robotic prostheses for military veterans. He and his fellow club members have dedicated countless hours to their robotics endeavor, staying at school until 8 p.m. most days. They say they are determined to win their next competition. Bragging rights and millions of dollars of scholarship money are on the line.

Always working away alongside them will be Felber, whom some students have come to call “mom.”

“If I want my life to have depth and meaning, I think I belong here,” she said. “I don’t have kids, so I get the biggest kick working with them. These kids are my whole life.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy