Friday, April 20, 2012 | 2 a.m.

Related content

Tony Hsieh bounces from table to table inside the Downtown Cocktail Room, quizzing college students.

The students, mostly from East Coast universities, are competing for the opportunity to spend two years working with start-up companies downtown, learning the ins and outs of business.

The objective of this exercise: see if the students are the right fit for the tech-friendly urban environment Hsieh is trying to create.

Someone asks a student what crime he would commit if he could get away with it.

Hsieh volunteers an answer: a “Mission: Impossible”-style heist.

When it’s his turn to quiz the students, Hsieh asks more than one: “What misperception do people have about you?”

One says people think she’s a perfectionist. Another responds that he’s often viewed as more confident than he is.

This time, Hsieh doesn’t turn the question on himself.

By now all of Las Vegas knows the 38-year-old CEO of Zappos is intensely interested and invested in downtown. He is moving his company there. He’s using a chunk of his fortune — he’s worth nearly $400 million — in an attempt to help transform the area from a decaying afterthought to an incubator for things the city longs for most — new businesses and a sense of community.

But what is the motivation behind that endeavor?

For all that’s been written about Hsieh, little is known about what drives him and his ambitions, civic and financial.

Some speculate it’s ego, a desire to remake downtown in his image — his personal Hsiehville. But others say Hsieh looks like a young Buddha, hinting that some Eastern religious ethic accounts for what can be viewed as a selfless endeavor. Still others say he can’t pass on a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to help remake the urban center of a city known around the world.

•••

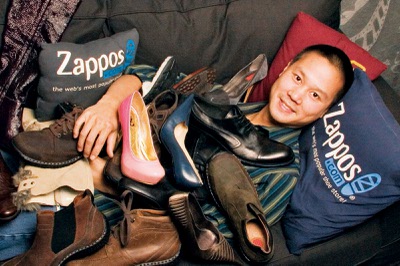

Hsieh’s interest in downtown’s progress begins with Zappos, the online shoe and clothing retailer he helped found in 1999.

In about 18 months, the company, which was purchased by Amazon for $1.2 billion in 2009, will have moved its headquarters from Henderson into the renovated City Hall building.

Hsieh has already made the move. He lives in the Ogden downtown high rise.

To understand this aspect of his interest in the area requires understanding Zappos, which is known in the business world for its quirky corporate culture that has turned the drudgery of call-center work into a career for enthusiastic employees.

A few examples: New hires are offered thousands of dollars to turn down the job offer. Cubicles are elaborately decorated. There’s no limit on the time an employee spends on a customer call. And there’s an open bar for employees who want a shot of whiskey or vodka or a beer on the job.

The effect is a collaborative and fun workplace. When someone gets a promotion, others don’t grouse about how it should have been them — they cheer.

As an outgrowth of that ethos, Hsieh wants to give his employees a downtown they can call home, not a longer commute to a decrepit neighborhood. He’s sure it will make them better employees, and better employees make better profits.

This has motivated Hsieh to put money into the ailing education system and the arts, and invest in small businesses that are the backbone of a neighborhood. He’s also working to attract high-tech start-ups.

Michael Cornthwaite, who operates the Downtown Cocktail Room and the Beat/Emergency Arts and has known Hsieh since 2007, said Hsieh’s interest in downtown is about far more than money. To him, Hsieh is a George Bailey-like figure, the decent, community-oriented character played by Jimmy Stewart in the Christmas classic “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

“The world, the way it exists now, is about power and money,” Cornthwaite said. “But he doesn’t see it that way — that ‘now that I have all this money, I’m a member of the club.’ He sees it like the club sucks and there’s a better way. He knows money doesn’t bring happiness, but it gives him the tools to bring happiness to other people.”

•••

On a morning two weeks ago, Hsieh walks from the Ogden to the Beat coffee shop. As he sips a bitter double-shot of espresso, he listens to tentative plans for a small grocery store downtown.

He then hops in the backseat of a chauffeur-driven Cadillac — he normally rides in the front, but on this day he has a guest — for a ride to Zappos’ headquarters in Henderson. His driver, Steve, an Iowa native who used to drive buses for Kid Rock, Machine Head and Etta James, is at the wheel.

Hsieh drives — he owns a Mazda 6 — but prefers to work while he travels, typing on his laptop.

At the office, he gets more coffee and walks to the Beatles room, decorated with posters and photos of the legendary band. Hsieh immediately opens his laptop. Arun Rajan, the company’s quick-to-smile chief technology officer, and Matt Burchard, senior director of marketing, enter the room. All are wearing tennis shoes, jeans and T-shirts.

Zappos has more than $2 billion in gross sales, but its meetings feel like a gathering of the coffee-shop regulars.

The three talk, hardly lifting their eyes from their laptops. They communicate in short phrases, almost grunts of acknowledgment, interrupted by a clear directive now and then. While one person talks, the other two tap away on their computers, sending emails, sometimes to each other.

Hsieh says it’s more efficient, especially in large meetings, because people who don’t have to be involved in a conversation can get work done.

They brainstorm how to increase Zappos’ Facebook presence.

“Facebook actually posts engagement metrics now,” Hsieh says. “Zappos is now 240,000 ‘likes,’ and 4,000 are talking about Zappos.”

It’s a week before Easter and Burchard mentions that the “Happy Hunt” is coming up that weekend in Portland. The company hides 100 eggs around the city that contain Zappos products and gift cards valued between $50 and $500. Clues are distributed through the company’s Twitter account.

“Why don’t we do that in Vegas?” Hsieh asks.

The question isn’t forceful, but he waits for the answer, chin in one hand as his other hand rests on the laptop keyboard.

Burchard says it was originally scheduled for Seattle, where Amazon is based, before moving to Portland.

“I’m sure that’s something people here would be interested in,” Hsieh says.

Burchard talks about the fact that people in Portland have more discretionary income and that Zappos is already well-known in Vegas.

“We can start doing more in Vegas,” he says.

Meeting done, Hsieh walks by his desk, which is located among other desks. He picks up a few books and heads back downtown.

•••

Hsieh doesn’t tolerate boredom. He is not interested in a job that he doesn’t like, he writes in his New York Times bestseller, “Delivering Happiness.”

Outside work, he lives in a world of ideas, surrounding himself with renowned thinkers. He flies them in to spend time with him and consult and hires them to speak to Zappos employees at quarterly meetings.

At an employee meeting last year, for example, he flew in a professor to talk about his research into how speech develops in children. Another speaker talked about the necessity for clean water in poor countries, prompting employees to organize on behalf of the charity.

As a computer science nerd at Harvard, then a businessman with Zappos, Hsieh had no formal training in urban development when he announced plans to move Zappos downtown. But he has met almost daily with someone who gives him more information on the subject and offers ideas about his plans.

He’s formed teams of Zappos employees who are focusing on technology/start-ups, education, entertainment and other areas of urban life. He plans to invest $350 million over the next several years in downtown.

Now when he discusses plans, he sounds like the experts he’s been listening to and reading.

Hsieh seems willing to try out almost any idea.

“I think it has to do with the fact that he, we, have never done it before so we haven’t been told, ‘You can’t do that,’” said Zach Ware, campus/urban/startup development leader at Zappos and the Downtown Project.

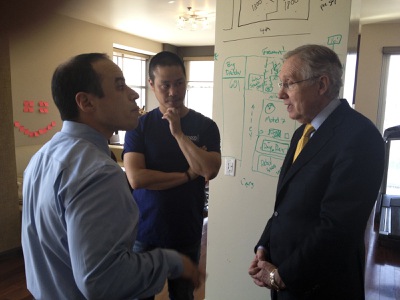

On this day, Hsieh is entertaining a Stanford physician who just moved to Las Vegas to launch a downtown health care project with his wife, a radiologist. He’s also waiting for Sen. Harry Reid to arrive. It will be their first meeting. No one, not even Hsieh, is exactly sure why Reid plans to visit.

When the Senate majority leader arrives, Hsieh shows him schematics of planned remodeling of downtown buildings. After being introduced to the anesthesiologist, Reid reminisces about a hospital that used to be located downtown.

Then the senator notices the robot. It belongs to the founders of a company called Romotive, which produces robots that can be controlled remotely using a smartphone.

The young men tell Reid that with new software, their robot could be operated using wireless Internet from any point in the world. Reid says something about potential military applications. Military robots cost as much as $10,000 or more; theirs, they say, is about $100.

Reid leaves. Within an hour is another scheduled visit with Peter Diamandis and some of his staff. Diamandis is the founder of the X-Prize, which offers millions of dollars to inventors who can solve practical problems — a vehicle that travels 100 miles on a gallon of gas, for example. He is also founder of Singularity University and just released a new book, “Abundance.”

Hsieh says that after visiting with Diamandis, he’s always left thinking, “I’m not going big enough.”

Ware tells Diamandis that the idea is to develop downtown “so it becomes the glue that holds people together: It’s a place you remember where you met so-and-so, so passions are all centered in one place. That’s a pretty cool thing.”

But it also has to have the kinetic energy to hold Hsieh’s interest. During a recent trip to a ski-resort town, Hsieh told Cornthwaite’s wife, Jennifer, that he could never live in a sleepy resort town “because there’s no sense of progress, of moving forward. ... Snow on the mountain, you ski, go to bed. But nothing’s going to change.

“So I think he really likes progress. It’s just a way of living where you want to continually evolve. And at the end of the day, there’s a sense of accomplishment.”

Later at the Downtown Cocktail Room, Hsieh, Diamandis and others drink and discuss theories about the universe, “Star Trek” and humorously devise potential future X-Prizes. After a couple of shots of Fernet, the group leaves and begins walking toward Le Thai, a few storefronts away.

At the corner of Fremont and Las Vegas Boulevard, a Metro Police officer holds up one hand. “Back up,” he orders.

A film crew is at work, and one block of Fremont Street, from Las Vegas Boulevard to Sixth Street, is off-limits to pedestrians.

Hsieh recently purchased the building he’s being prohibited from walking past. “Did anyone notify you that this was going on?” Hsieh asks Cornthwaite, who answers no.

Others say none of the businesses on Fremont were told the crew would be filming.

It’s the one-year anniversary of Insert Coin(s), whose customers can’t get to the arcade.

Suddenly, an elderly couple from Idaho stops.

“Are you Tony Hsieh?” the woman asks. “We toured Zappos last year!”

The police officer hears this, acts like he doesn’t, then huddles with another officer.

Soon someone from the film crew escorts Hsieh and his entourage to the restaurant.

While people close to Hsieh rarely demonstrate negative emotion, Ware is noticeably annoyed. He and other business owners have been asking the location manager to see the crew’s permit. She can’t produce one. By 9:30, police and film crew are gone and customers can again reach businesses.

(City officials later say the crew did not have a permit to film that night. The location manager sends an apologetic email saying she was under a lot of pressure.)

•••

Hsieh describes himself as shy. When he looks at ways to improve his company’s culture, he often invokes the concept of “serendipity” — architecture and design that improves the chances of happenstance meetings. He believes it increases idea-sharing, friendships and the workplace.

For the shy person who isn’t inclined to reach out to others, serendipity is a gift.

As he meets with designers from New York to lay out plans for housing downtown, Hsieh emphasizes the concept. The designers like it, but Hsieh wants them to think bolder.

“What about a bar in the elevators?” he asks.

The designers half-smile, then chuckle.

A bar in a large elevator would encourage talk among residents of a large complex in a place usually dominated by uncomfortable silence.

Hsieh is also unfailingly polite. He never takes over a conversation or a meeting if someone else has the floor.

Friends describe him as gracious, generous, kind. When a group of elderly people approaches him at a farmers market in the old bus depot downtown, Hsieh stops.

“TO-neey!” one says, grabbing his arm. He dutifully poses for a picture.

He says he’s not interested in politics. What might border on the political is his refusal to give money as a one-time gift with no plan for it to be used to perpetuate a business or the public welfare. He invests in people who are passionate about an idea.

His parents drove him to succeed, he admits in his book. But at a Thanksgiving dinner last year, where dozens of friends gathered at his condo, Hsieh’s parents came off as low-key and unassuming.

“My mom still hopes I get a Ph.D,” Hsieh says.

•••

It’s First Friday, the monthly arts confab downtown. Ware hosts a party beforehand at his Ogden condo. After an hour, the group of about 40 takes Zappos buses to the event, which Hsieh and other investors purchased last year.

The buses are equipped with a bar and bartender. Drinks are free. Ware says they are looking at ways to allow the public to experience the bus ride.

The partygoers separate and disappear into the crowd. Hsieh busies himself texting an acquaintance, asking his whereabouts.

Shy but interested in interacting with others, kind but with business smarts, inquisitive, Hsieh sees using his wealth to benefit a city as more enjoyable than if he were just doing it for himself.

Why? “Definitely not” to have someone erect a statue or have a street named after him, he says.

Part of it is solving a puzzle that many have believed is impossible.

“It’s like a really big, complicated puzzle that doesn’t get boring,” he says. “Entrepreneurism is about being able to combine creativity, optimism and execution.

“It’s good for me since I live downtown, it’s good for Zappos because it’ll help us attract and retain more employees. It’s good for the city, and, ultimately, hopefully, it will help inspire other cities to revitalize themselves.”

That simple. That complex.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy