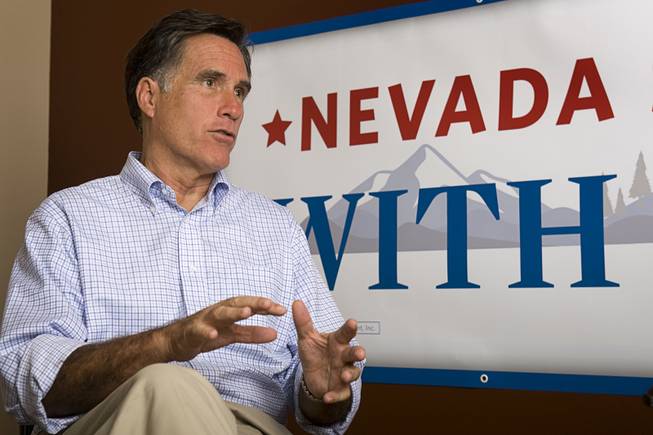

Former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney responds to a question during an interview in Las Vegas Monday, Oct. 17, 2011.

Friday, Oct. 21, 2011 | 2 a.m.

J. Patrick Coolican

Sun Topics

Related stories

Early this week, Mitt Romney, in town for the Republican presidential debate, had this to say to Las Vegas residents who have thrown their money into the black hole of the real estate market: Tough luck.

That’s a paraphrase, but his quote to the Las Vegas Review-Journal means just about the same thing: “Don’t try and stop the foreclosure process. Let it run its course and hit the bottom, allow investors to buy homes, put renters in them, fix the homes up and let it turn around and come back up.”

Hard as it is to hear for Las Vegas residents, Romney might be right, according to real estate experts and economists from across the spectrum.

Preventing the bubble by raising interest rates and enforcing tougher lending standards was the proper policy. Once the bubble inflated, however, it had to deflate and prices had to reach equilibrium before there could be any recovery.

The government could have given money to homeowners instead of banks in 2008, but the bubble hadn’t deflated yet, so those homeowners would have again been deep underwater within a year or two, and the banks would be in crisis because they’d still be holding bad assets.

The federal government’s Home Affordable Modification Program, or HAMP, has been useless to Nevadans because to tap the program the homeowner can only be 10 percent underwater, whereas the average home in Clark County is 27 percent underwater, according to Nasser Daneshvary, director of the Lied Institute for Real Estate Studies at UNLV.

Nevada’s mandatory mediation program, which puts at-risk homeowners and lenders in front of a mediator to try to work out new terms, was passed by then-Assembly Speaker Barbara Buckley and is now championed by Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval as a national model. But in the face of mass unemployment and so many Nevadans happily choosing to walk away from their mortgages, the program is a soldier on horseback fighting a column of tanks.

Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research who predicted the crash, says the federal government’s response has been “crazy” because it never acknowledged the bubble and was too focused on reinflating it. Bottom line, according to Baker: The bubble must deflate, and although it’s deflated here and in Phoenix, he thinks there’s a ways to go in markets such as Los Angeles and San Diego.

But the feds never properly distinguished between markets where loan modifications made sense because they were near the bottom, and others where a loan modification was just a short-term fix because prices were bound to fall much further. And of course banks haven’t been helpful, often refusing to consider modifications for homeowners able and willing to continue making mortgage payments.

Mike Calabria, of the libertarian Cato Institute, calls the wandering approach — which he noted has been tried by both parties — “building a bridge to the next bubble.”

The good news, here in Las Vegas: “We’re moving to clear the market,” says Robert Lang, the director of Brookings West and a real estate expert and consultant. In other words, stuff is selling, including 4,700 existing homes in August, the second-most ever.

(Other states with more sluggish foreclosure processes are moving slower.)

Even though prices in the valley were down 8.9 percent in September compared to a year earlier, 8.9 percent of nothing is much smaller than 8.9 percent of a lot, and price stability can’t be far behind this high velocity of sales.

By one way of thinking, the faster we get people out who can’t or won’t pay their mortgage and replace them with new owners, the faster we get to stability.

Another upside of the collapse in prices: Las Vegas real estate — both residential and commercial — is suddenly very affordable for retirees and business owners, giving us a competitive advantage.

A do-nothing policy is not without risk or collateral damage, however.

Neighborhood blight — empty homes, absent owners, ne’er-do-well renters — is a problem. Baker advocates a “right-to-rent” program wherein the homeowner would give up the home but be entitled to rent it from the bank or new owner at a fair market price determined by an assessor. This would give neighborhoods continuity.

There’s also the risk that the same mass psychology that gave rise to the bubble will work in reverse: As prices continue to decline, people who bought in 2009 and 2010 and aren’t that far underwater grow hopeless and still walk away from their property, which in turn pushes up supply and forces down prices still further.

According to a University of Chicago study, 35 percent of mortgage defaults are “strategic,” meaning the homeowner could pay but decides not to because the investment has become worthless.

Once people stop believing this is the rational choice, we’ll know we’ve reached some stability.

One way to stop it: Massive principal reduction — reduce what the borrower owes to something closer to market reality. Former Reagan administration economist Martin Feldstein called for this in a recent New York Times Op-Ed.

His proposal would reduce principal to no more than 10 percent above the current market price for the property; in exchange the borrower would agree that the bank could chase him down for the balance were he to walk away.

Daneshvary agrees with this thinking. “I can let the forest burn, but it will take years for the seeds to come up.” Put the fire out now, and the rebuilding can begin.

Of course, someone has to pay for principal reduction: Either the banks, or the taxpayers, or some combination of the two.

As Lang says, “Where’s the money come from?” The politics are brutal, as Wall Street has a solid grip on both parties, and taxpayers are loath to pay down someone else’s mortgage.

For whatever you think of Romney and his callous message to Nevadans, the lesson here is this: Once you’ve fallen for the scam — be it Tulips in 1630, Pets.com in 1999, or Las Vegas houses in 2005 — you shouldn’t expect to get repaid. The money wasn’t there in the first place.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy