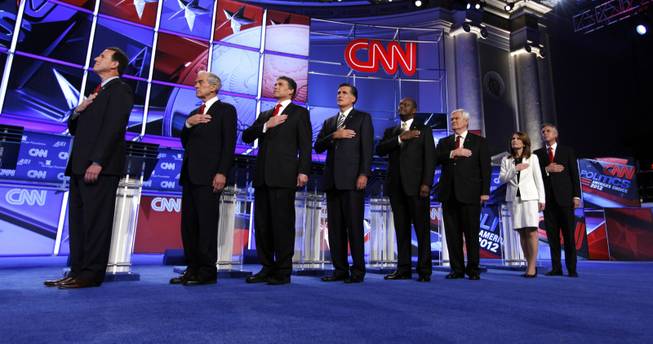

Evan Vucci / AP

Republican presidential candidates from left, former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum, Rep. Ron Paul, R-Texas, Texas Gov. Rick Perry, former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, businessman Herman Cain, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, Rep. Michele Bachmann, R-Minn., and former Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman stand for the National Anthem before a Republican presidential debate in Washington, Tuesday, Nov. 22, 2011.

Wednesday, Nov. 23, 2011 | 1 a.m.

When a party is picking a president, there’s something about foreign policy debates.

Four years ago, foreign policy played a significant role in turning Barack Obama from the young senator with a great political aesthetic into the serious front runner who would eventually win the nomination.

He took a harder stance than most of his opponents against the Iraq war, insisted on a new era of diplomatic engagement, and while his fixation on Pakistan and pledge to chase al-Qaeda terrorists there with or without the cooperation of local leaders was shocking at the time, it helped make him look like more of a commander-in-chief than Hillary Clinton (not to mention eventually nab Osama bin Laden).

Foreign policy debates can define who’s shaping up to be a party’s nominee for president.

Or, as was more the case with the Republican foreign policy debate Tuesday night, they can define who may shape up not to be.

Tuesday night’s CNN debate at the Daughters of the American Revolution Constitution Hall — just two blocks from the White House — wasn’t the first foreign policy face-off of the primary season, but it was the purest.

Candidates delved deep into debates about the Patriot Act, terrorism, a nuclear Iran, and the Arab Spring. They barely mentioned the economy, and there was nary a peep about housing (even though timing-wise, it was the debate where new front runner Newt Gingrich should have been taken to task for the $1.6 million he earned from subprime lending giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac).

There were actually a lot of foreign policy credentials on the Republican presidential debate stage: Jon Huntsman was an ambassador to China; Michele Bachmann serves on the House Intelligence Committee, where she’s privy to some of the most clandestine information on foreign threats; Rick Perry has had substantial experience policing the southern border; and there’s no better issue area for Ron Paul to drive his pro-liberty, anti-imperialism message home.

But so far, the national polls don’t believe any of them are going to be the Republican presidential nominee. Right now, this is still about the big three: Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, and Herman Cain.

Let’s start with Cain.

Cain’s foreign policy weaknesses have been on national display for the last week, since a video showed the front runner draw a blank on a question about Libya during an interview with the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel; Cain wasn’t able to articulate any specifics about his position or President Barack Obama’s or where they differed.

He followed that up Tuesday night with answers to foreign policy questions that were either overt dodges or downright uninformed.

On whether the United States can continue to fund foreign assistance to Africa: “It depends on priorities. Secondly, it depends upon looking at the program and asking the question, ‘Has that aid been successful?’” he said. “What have the results been? Then we make a decision about how we prioritize.”

(President George W. Bush’s initiatives to combat AIDS and malaria have been roundly praised by members of both parties as very successful, and important for American national security. Moreover: Rick Santorum had just said so right before Cain gave that answer.)

On whether the United States should support a no-fly zone in Syria: “No, I would not,” Cain said. “I would work with our allies in the region to put pressure to be able to try and get our allies and other nations to stop buying oil from Syria.”

(Syria produces only 0.5 percent of the world’s crude oil, and presently, Iran is its only major customer. Economists believe Syria will be a net importer of oil in the next three to five years.)

Romney’s answers, meanwhile, showed him to be far better informed. But he wasn’t sticking his neck out much further than Cain on the treacherous issues.

Romney gave a more informed answer than Cain as to why the U.S. should not pursue a no-fly zone in Syria. “This is a nation which is not bombing its people, at this point...They have 5,000 tanks in Syria,” he said. “A no-fly zone wouldn’t be the right military action. Maybe a no-drive zone.”

But on the much larger subjects of Afghanistan and the threat of a nuclear Iran, he played it safe, primarily using each of the subjects to pick at Obama’s policies instead of detail his own.

On Iran: “We’ve been talking about Israel and Iran. What we’re talking about here is a failure on the part of the president to lead with strength,” Romney said. “If I’m president of the United States, my first trip — my first foreign trip will be to Israel to show the world we care about that country and that region.”

On Afghanistan: “I stand with the commanders in this regard and have no information that suggests that pulling our troops out faster than that would do anything but put at great peril the extraordinary sacrifice that’s been made,” Romney said, even as Huntsman chided that as commander-in-chief, he’d have to be more assertive than that.

Gingrich, by comparison, was neither uninformed nor timid, but as a result, he got into two jams Tuesday night.

The first — a tough-talk-laced-with-nuclear-fear-mongering warning that America needs the Patriot Act because “all of us will be in danger for the rest of our lives” — threatened to cripple Gingrich after Paul got cheers for retorting that the Patriot Act was “unpatriotic” and arguing, “You never have to give up liberty for security; you can still provide security without sacrificing our Bill of Rights.”

But Gingrich wrested back the spotlight after Paul misstepped, crediting the country for having done “rather well” with Oklahoma City bombing terrorist Timothy McVeigh without the Patriot Act.

“I don’t want a law that says after we lose a major American city, we’re sure going to come and find you,” Gingrich shot back. “I want a law that says, you try to take out an American city, we’re going to stop you.”

But it’s not clear if Gingrich yet will work his way out of a second trap — one he set for himself — on immigration.

Gingrich advocated for a program to legalize the status of many of the 11 million undocumented workers in the country without putting them on a pathway to citizenship. “If you’ve been here 25 years and you got three kids and two grandkids, you’ve been paying taxes and obeying the law, you belong to a local church, I don’t think we’re going to separate you from your family, uproot you forcefully and kick you out,” he said.

That didn’t sit well with Bachmann, Perry or Romney.

“I don’t agree that we should make 11 million workers who are here illegally legal,” Bachmann said. “That, in effect, is amnesty.”

Gingrich fired back, “As somebody who believes strongly in family, you’ll have a hard time explaining why that particular subset is being broken up and forced to leave, given the fact that they’ve been law-abiding citizens for 25 years.”

Gingrich wouldn’t be the first Republican to be brought down by a moderate position on immigration, but neither would he be the first Republican to win a party nomination with such views: both John McCain and George W. Bush did it, and both of them took a more moderate stance than Gingrich.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy