A truck outside of Border Inn on the border of Nevada and Utah on Highway 50 on Sunday, August 7, 2011.

Thursday, Aug. 18, 2011 | 2 a.m.

J. Patrick Coolican

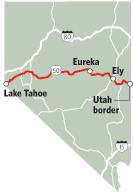

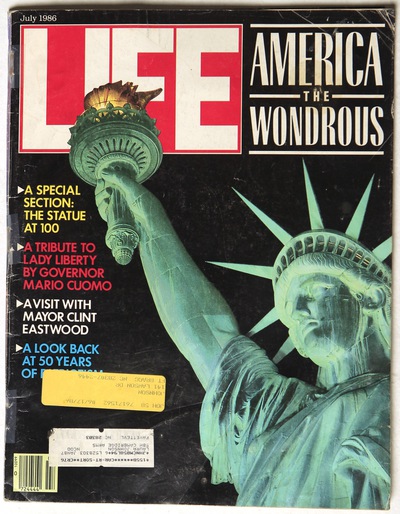

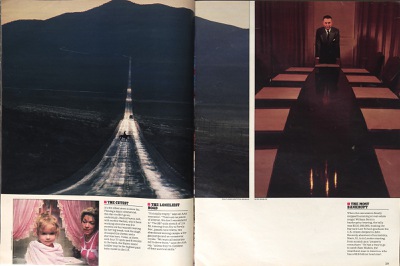

Editor’s note: Twenty-five years ago this summer, Life magazine named U.S. Highway 50, as it crosses Central Nevada, the loneliest road in America. A photo of a straight stretch of empty highway fixed it in the national imagination as a symbol of the state’s vast emptiness. To mark the anniversary of the Life photo, columnist J. Patrick Coolican and photographer Leila Navidi drove the length of U.S. 50 in Nevada to examine issues important in the rural communities along the highway, meet its people and explore loneliness in the hyper-connected age.

BAKER — At T&D’s restaurant in this hamlet near the Utah border, the talk turns to water almost immediately.

“What about our water problems — Las Vegas trying to steal our water,” says Rouena Leonard, a semi-retired British-born waitress.

Her friend, the owner Terry Steadman, who dropped out of the corporate grind to move here 20 years ago, quickly joins a discussion of the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s proposal to build a pipeline and pump water out of the lush valleys of the Great Basin and to Las Vegas.

Steadman’s jaw looks hard, like the quartzite of Wheeler Peak that looms above. Perhaps it’s the result of years as a small businessman — the restaurant he and his wife own doubles as the town’s grocery store — in one of the remotest places in the Continental United States.

Or maybe the clenched jaw comes from this water discussion. The former AT&T engineer speaks fluently about the science and politics of what people here in the Snake Valley believe is a water grab the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the infamous William Mullholland drained Owens Lake and then began pumping groundwater to Los Angeles.

“Hopefully sanity will prevail,” Steadman says.

Does it ever?

The Water Authority has acquired massive ranches with the intention of building a $3.2 billion, 306-mile pipeline that could deliver 184,544 acre-feet per year, which would support twice that many families of four, or more than a million people. The Water Authority must obtain the water rights from the Nevada state engineer, while also winning right-of-way access for the pipeline to cross federal land from the Bureau of Land Management.

To the surprise of many, however, the residents of Snake Valley, who are remarkably united in their opposition, are holding firm, refusing to sell and fighting back on several fronts, including in the courts.

Meanwhile, opponents are quietly content over a draft environmental impact statement finally released by the bureau in June, after six years of input from the Water Authority, residents, tribes and a litany of federal agencies.

The prose is turgid and reserved, but the environmental conclusions are often stark:

• “... likely result in windblown dust emissions due to drying of hydric soils and loss or reduction of basin shrubland vegetation.” People in Utah, downwind, are particularly alarmed by this prospect.

• “... risk of subsidence of the ground surface as a result of the withdrawal of the groundwater.” This means the pumping could cause the ground to sink several feet over hundreds of square miles, causing buildings, transmission lines and roads to be structurally unstable.

• “... risk of invasion by invasive ... species.”

• The pumping could affect surface water, such as ponds, lakes and streams, which would obviously adversely affect the species that rely on that water for drinking, foraging, breeding.

• “Drawdown poses long-term risks to the agricultural sector in the rural areas...”

I could go on.

Water Authority spokesman J.C. Davis says the BLM study, which is still merely a draft, was built with assumptions that are just that, assumptions, as well as computer models that should not be mistaken for certainty. Hence the document’s persistent use of words like “potential,” “possible” and “could.”

He says it’s the BLM’s job to envision “maximum conceivable footprint.” And so he means no criticism when he says the report is a “dramatic overstatement of what will actually happen.”

Davis says the Water Authority would be bound by strict limits on what it could pump, specifically, what the state water engineer says is the perennial yield, or the natural recharge through snow melt and rain.

Rob Mrowka of the Center for Biological Diversity says this doesn’t allow for the water required by deep-rooted plants to survive. In other words, Mrowka says, “It doesn’t allow the ecosystem to have its fair share.”

Hence the death of the deep-rooted shrubs that live off the water below the surface and, with it, the dust.

Davis says that to begin with, not all the important shrubs will die. And, he says, the assumption of vegetation loss is mistaken because it fails to take into account the replacement of some species of plants by others, through natural processes, through the Water Authority’s own mitigation efforts, and, yes, he concedes, through invasive species. These replacements would help prevent the dust that’s so feared.

Mrowka counters that the replacement species would be far less effective at dust control because they are annuals — they die every fall.

Davis says the pipeline and its effects would be closely monitored by the Water Authority, the state engineer and several federal agencies whose job it is to protect federal land, waters and species.

If the pumping regimen needs to be changed, it can be changed.

Davis points to the Water Authority’s admirable record of environmental responsibility. This is especially true of its conservation efforts, which have been aggressive — by 2035, conservation will allow it to use 276,000 acre-feet less per year.

Based on this record, Davis is essentially saying we should trust the Water Authority. If the agency is as monstrous as the opponents of the pipeline seem to believe, “We’d have to want to do the wrong thing. And then we’d have to blow through all the safeguards that are in place. If you believe that stuff, well, there’s nothing I’m going to say that’s going to convince you.”

Rural Nevada is mistakenly believed to be a barren place, a fiction that can only be laughed at when you drive to the Snake Valley and Nevada’s only national park, Great Basin National Park. Although it sits on America’s loneliest road, it’s brimming with life and a rich geologic and ecological history of tumult.

The Great Basin was once a shallow sea before experiencing volcanic eruptions and then a relentless stretching of the earth’s crust, creating the repeated mountain-basin formations. The aquifer beneath the region dates to the ice age.

And depending on where you are, there does seem to be a lot of water.

While Baker Creek runs fast, a cold wind blows through the pines. During an early morning walk to an alpine lake in the shadow of Nevada’s second-highest mountain, Wheeler Peak, we see limber pine, quaking aspen, Englemann spruce, Douglas fir and 3,000-year-old bristlecone pine.

In a clearing, a herd of mule deer is grazing, eyeing the watchers.

Andy Ferguson, superintendent of the park for three years, says he’s concerned about the pipeline, fearing it could have unknown effects on the park’s famous caves, which are a big draw, and also its springs, streams and lakes, and the species that rely on them. He’s also concerned about what could happen to the park’s feeder town of Baker. Every good park needs a town so visitors can get petrol, food and other supplies.

Ferguson wonders what would happen to Baker if the region no longer supports agriculture.

The man to talk to about agriculture is Dean Baker, the iconic rancher who has spent more than half a century working his ranch but now devotes himself fully to fighting the pipeline.

Baker says he knows the effect drilling will have on the region because he’s seen with his own eyes what pumping and irrigation have done to his own springs.

The entire aquifer is more fragile, more interconnected and less knowable than is imagined, he says.

The most compelling argument for the pipeline, the only argument really, is that we need the water.

Opponents say we don’t, or that we should get it from somewhere else, or merely conserve more.

The Water Authority says we need it, and I suppose I’m not in any position to argue. And I’m certainly not in any position to argue with my fellow Las Vegans, who are raising families and trying to build this into a better community, one that obviously cannot survive without water.

We’re not the only ones with a horizon and a need for water though.

At the Border Inn on the Utah line, owner Denys Koyle points at the two young sons of a ranch hand: “These guys don’t have a future if the water goes.”

Next stop: Ely.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy