Saturday, April 30, 2011 | 2:05 a.m.

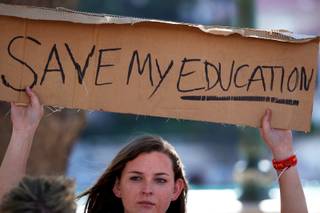

Student protest

KSNV coverage of protest by valley high school students over proposed education budget cuts, April 29, 2011.

20 Answers

Sun coverage

Sun archives

- Students skip school to protest education cuts (4-29-2011)

- Las Vegas teachers protest proposed education cuts (4-27-2011)

- Teachers take fight over education funding to streets (4-13-2011)

- District to cut 200 bus driver positions, change school start times (4-8-2011)

- School District gives early approval to budget that cuts 2,500 positions (4-6-2011)

- Higher ed system responds to lawmakers, details impact of budget cuts (4-5-2011)

- UNLV president presents cuts, says they are “a tragic loss and a giant step backward for Nevada” (3-8-2011)

- Assembly passes bill to use reserves for school construction (3-3-2011)

- Democrats say Sandoval budget has $325 million hole (2-24-2011)

- UNLV president’s somber warning on budget cuts moves faculty to tears (2-16-2011)

- Regent says it’s time that K-12 shares in budget sacrifice (2-8-2011)

- Higher education officials say Sandoval budget cuts a ‘death sentence’ (2-4-2011)

- Education in forefront of upcoming budget battle (1-30-2011)

- Chancellor: University tuition would have to go up 73 percent to cover Sandoval budget gap (1-27-2011)

- School officials warn of jobs cuts, larger classes under proposed budget (1-26-2011)

- A steep climb for Nevadans (1-26-2011)

- Soft words during State of the State hide Nevada in pain (1-25-2011)

- Teachers not pleased with most of Sandoval’s speech (1-25-2011)

- In response, Democrats say taxes might be part of budget solution (1-24-2011)

There’s an intersection just west of Summerlin Hospital, where Hualapai Way crosses Crestdale Lane. On one corner sits a park where children play soccer and lacrosse. Several hundred yards away is Bonner Elementary School, one of the better performing elementary schools in the Las Vegas Valley. The crosswalk has stop signs, no traffic signals and young children warily attempt to cross five days a week on their way to and from Bonner. Drivers race through the intersection without stopping. You can spot the skittishness in the body language of many of the youngsters, but somehow drivers don’t see it or care to look. You can’t help but wonder, if we’re not willing to stop for 8- and 9-year-old children as they enter those crosswalks, why would we ever do enough to educate them?

Our parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and neighbors did just that for many of us, but those were generations raised during an era of hardship — the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, World War II. They understood self-sacrifice, the need to forgo a meal and a cup of milk so their children or younger brothers and sisters could thrive, let alone survive. They were the beneficiaries of a multitude of New Deal-inspired programs and attitudes that provided a future. A large percentage were educated by a nationwide network of public schools, which linked students, parents, teachers, administrators and the broader community.

Those of us raised during and since the Reagan years were taught to believe that government is the problem, not the answer, and taxes are not the dues of an enlightened society but rather the wages of an insatiable behemoth. We find reasons to tear at the foundation of our public school system, which contributed to the economic boom of the 20th century. And now we look the other way. Stop for those kids in the intersection? They’ll be OK. We roll through and not look back.

It’s a commonly held belief: We have an education crisis in Southern Nevada. Our high school graduation rates are among the worst in the country, so too our standardized test scores. Per-pupil classroom spending is among the lowest levels in the nation and continues to fall amid state budget cutting. Too many of our children can’t read, write or synthesize concepts at acceptable levels. The lamentable refrain — we’re atop the worst rankings and buried at the bottom of the best — is heard throughout the community. Everyone seems to have an answer for what ails the Clark County School District: More money. Less money. Community control. Fewer administrators. Financial incentives for teachers. Tougher tenure requirements. More bilingual classes. What’s certain is this: Nothing is certain.

Nevada wasn’t built with an emphasis on education. Raw minerals, gambling, hotels, prostitution, transportation, agriculture, construction and the military have been and continue to be the foundations of our economy. Although some segments required highly educated workers, the success of the state was largely built with the skills of blue-collar workers who had traditional training in reading, writing and arithmetic and required little in the way of advanced education. But the world has changed. Workers are expected to synthesize multiple skills at a much higher level, and if they don’t there are fewer opportunities awaiting them and our state.

Gov. Brian Sandoval has spoken of the need to diversify the state’s economy, to lure new businesses that will carry the state through the coming decades, but proponents of the strategy argue that strong public schools, colleges and universities are needed to recruit and retain the businesses that would jump-start that diversification effort. For them, Sandoval’s no-new-taxes pledge is a shortsighted approach that will stunt the state’s development efforts.

UNLV President Neal Smatresk said of the governor’s proposed budget cuts: “It’s a very, very serious moment in Nevada history. It’s unimaginable. It’s unimaginable if you believe we’re important to Nevada.”

The worst-case results from Sandoval’s cutting could find 315 jobs and 33 degree programs lost at UNLV and 2,500 to 4,500 jobs in the Clark County School District.

Sandoval’s senior adviser, Dale Erquiaga, the former No. 2 lobbyist in the Clark County School District, says the choice is clear: “We can’t extract more tax dollars from the economy without (causing) harm. From our perspective, you have to change the system. Simply adding money or taking money (from the state’s public schools) hasn’t worked at all. That’s our challenge.”

Sandoval seeks to end what’s informally known as teacher tenure and wants what Erquiaga says would be a more thorough performance evaluation process for teachers. The governor also wants to eliminate the standardized pay scale offered by Nevada public school districts, with educators receiving raises based upon seniority and the number of advanced degrees attained. He wants to make it easier to fire bad teachers while rewarding good teachers for student performance.

Critics of the Sandoval plan view it as the latest assault by a Republican governor on the collective bargaining rights of unionized teachers, a large percentage of whom feel whipsawed by the political, social and economic changes that have overtaken this country. Public school teachers speak of the metaphorical target that’s been placed on their backs. Rather than holding a respected place in our culture, many believe that parents, politicians and taxpayers view them as highly skilled babysitters rather than highly educated professionals.

To be certain, the talent pool has changed through the decades. Before women had the right to vote; before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that separate was not equal; before Jews were allowed to live in the same neighborhoods as Christians and work as doctors and lawyers, our public schools were filled with teachers who were unable to find opportunity outside the classroom. Many were brilliant mathematicians, historians, writers and thinkers whose only hope for fulfilling work that challenged their intellectual abilities was in a public or private schools.

Graduates from the post-World War II era recall having teachers who today might have been a CEO, CFO, doctor or lawyer, but America of the 1940s and ’50s wasn’t that open-minded. The classroom was one of the few settings where they were allowed to shine. Then came the civil rights movement, women’s liberation, affirmative action and many of our best and brightest who might have ended up teaching had gained the opportunity to shine elsewhere. That’s not to say there aren’t first-rate educators in today’s classrooms. The problem is that the talent pool is thinner.

Talk privately with top-notch teachers and first-rate school administrators, and they’ll speak of colleagues and employees who went into the profession for the vacations, the breaks throughout the school year, the health insurance and retirement benefits, the chance to work in a school that their kids attend, the 8 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. work schedule.

What they often fail to see before taking the job are the real demands, the late nights, early mornings and weekends spent grading papers, preparing classroom plans, communicating with parents, completing government-mandated paperwork; attending before- and after-school meetings with co-workers and school administrators. A significant percentage fail to realize that they’re about to become surrogate parents and grandparents to their students, de facto counselors to parents.

Many don’t remember that their children sit in classrooms in a region that challenges the most mature adults. Nevada has some of the highest rates of adult suicide, depression, substance abuse and other addictions in the country. We live in a three-shift town where two parents often aren’t home at the same time if both are lucky enough to have jobs or if the family unit is intact. Many come from homes where English is not spoken.

Our region’s elevation to iconic pop culture status finds many of us placing a greater emphasis on the ephemeral, the sexual, the short-term rather than the ethereal, the intellectual, the long-term. To be certain, there are safety nets — churches, synagogues, mosques, community groups, neighborhood schools and extended families. Yet, the same challenges that tear at our sense of community, rip at our public schools.

Talk of economic diversification often begins with the plight of those schools. We hear stories of businesses that had considered moving here but didn’t because of the quality of our public schools and the graduates they produce. Few want to send their kids into those buildings.

The School District places the high school graduation rate at about 70 percent. Johns Hopkins University says it’s closer to 50 percent. The number you cite depends upon the assumptions you make about the students who disappear from the system. Did they drop out or simply move away? Are they done with high school or planning to return for their GEDs?

Southern Nevada businessman Steve Hill has struggled with the issue. Before the economic crash, Hill found it difficult to find young employees, particularly Clark County schools graduates, who were able to synthesize math concepts or read and think at higher levels, skills needed on many construction jobs.

Hill is a key player in a local concrete business and one of the state’s most active business voices for education reform. He has engrossed himself in the minutiae of classroom performance, teacher incentives, school district budgeting and their effects on the regional economy. He’s an outspoken champion of education reform through the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce and in recent weeks has been in Carson City meeting with top figures in the Legislature and the governor’s office. They’re attempting to lay the foundation for economic development and diversification and are seeking a full inventory of the state’s employment base, one that analyzes the number and types of employers, the quantitative and qualitative makeup of our workforce and an analysis of what the nation’s job market will be in the future.

Hill’s convinced that a thoughtful, strategic approach could broaden the employment base for years to come. Ironically, he’s not worried about finding qualified workers in today’s job market. “There are so many smart, qualified people out there looking for work,” he says. “That wasn’t the case five years ago.”

He frets that it won’t be the case in a couple of years when the economy finally rebounds.

Parents may find it difficult to articulate, but they sense that something is different. They worry about their children’s futures, not in the way that parents of an earlier generation did. Something has changed. The dream has been globalized, and now our children are competing in a world we never imagined.

Education activist Maureen Peckman, executive director of the Council for a Better Nevada, publicly articulated a similar concern five years ago during the search for a new Clark County schools superintendent. Peckman’s group sought to hire Eric Nadelstern, a reformer from the New York City public school system, to replace Carlos Garcia, who left his job in December 2005 to work in the private sector. Nadelstern was viewed as “an agent of change,” someone who would push for greater accountability in pursuit of higher high school graduation rates and improved student test scores.

Despite the support of Peckman and a group of 25 high-profile business and community leaders, Nadelstern withdrew from the process, saying the Clark County School Board didn’t fully support his candidacy. He feared that if he took the job, a split board wouldn’t support the reforms that he and the Peckman group sought, among them a push for greater accountability and neighborhood control of schools.

Peckman says School Board members were “in cahoots” with district administrators at the time to prevent Nadelstern from transforming the district. She characterized that dynamic as “one of the most dysfunctional aspects of our society,” school board members who raise $10,000 apiece to be elected to one of seven seats that determine education policy. “We’re getting the school district we deserve.”

Longtime district administrator Walt Rulffes was the other finalist for the position, which he took in early 2006. The amiable educator was credited with introducing the Clark County School District’s Empowerment Program, which has given principals, teachers and parents greater control over budgeting and hiring decisions at 30 schools. Yet, Peckman laments that concerns remain from the Garcia era. “I think you just need to start being honest with people, even if the news isn’t good,” she says. “People can handle really bad news. What they can’t handle is hopelessness. That’s when people stop showing up. That’s when students stop trying, and that’s when teachers stop teaching.”

She’s not shy about leaning on School District administrators and acknowledges that they take her calls because anyone of her group’s members could hold a news conference on a moment’s notice. Peckman pushed for the hiring of new Clark County schools Superintendent Dwight Jones. She says his commitment to education reform is needed in Southern Nevada. “We haven’t paid attention, the school board, the federal government. It goes back to thinking these kids can’t learn,” she says. “We haven’t kept the contract. We let you drop out. We said, ‘Go get a GED.’ We don’t follow up. We’ve completely let down on that contract. It’s what George Bush called the soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Peckman looks to Empowerment Schools as a model that works, one that hammers away at the power of the bureaucracy and provides control and oversight where it will be wielded the best. The Empowerment Program is headed by Jeremy Hauser, a 49-year-old former principal who has led three elementary schools in neighborhoods ranging from low income to upper middle class.

A soft-spoken native of Illinois, Hauser is the son of a Lutheran minister who would leave the Sunday dinner table to “minister to his flock.” He views his role as having a similar calling, one in which he meshes schools with neighborhoods. “You can’t allow yourself to believe anything other than we are the key,” he says. “On the other hand, we’re trying to define the most important unit, the neighborhood. Our goal is to bring people together.”

The Empowerment Program is designed to give parents, teachers and principals at the program’s 30 schools real decision-making authority to hire the mix of teachers needed in each building. Some may place a greater emphasis on math, others on reading, but Hauser warns that “you can never become more neighborhood-oriented than academically oriented.”

He notes that four of the 12 Clark County elementary, middle and high schools were identified as “high achieving” under federal No Child Left Behind testing are empowerment schools. He says the schools reduced the achievement gap for children who study English as a second language, and the three empowerment high schools — Moapa, Chaparral and Cheyenne — have increased graduation rates while decreasing dropout rates by single-digit amounts.

Yet, Chaparral was recently placed on a watch list for failing to meet its Annual Yearly Progress goals under No Child Left Behind. The school’s principal and about 80 percent of its staff are being replaced. Other empowerment schools struggle with students’ academic performance. Hauser says the failings often can be attributed to a failure to find “the right solutions” for a school’s community as well as having “the wrong personnel” in a building. When asked whether both reflect upon him, Hauser readily acknowledges that they do. “The results are what move it up to my level of responsibility,” he says.

The empowerment budget is expected to decrease to $100 million next school year from $115 million, with a decline in state and local support and the expiration of a three-year, $13.5 million grant from billionaire Kirk Kerkorian’s Lincy Foundation. Per-pupil spending in middle and high schools hovers at $3,600. But Hauser says it’s not all about money. He says neighborhood control is the future of education, demanded by the people who matter most — students and their parents — and he’s convinced that the schools superintendent, Jones, is equally committed to the concept. The key is leadership — charismatic, dynamic principals. “I’d like to hire a few of those,” he says. “You can change the energy of a school building immediately. Trying to find a Superman, that’s probably the idea. Actually, we can use multiple Supermen.”

The new superintendent has been on the job for four full months. A former Colorado commissioner of education, he has taught and was a school administrator in Kansas and Baltimore. No one’s certain how long he’ll be here or where he might be headed, but he’s viewed by community business leaders as a potential savior for what ails the Clark County School District.

In his first months in office, Jones has met with business, political and community leaders. What often emerges from those conversations is that the 48-year-old Jones is a true reformer, someone who’s willing to experiment and try things that others in the district have been reluctant to embrace. Where longtime officials view the district’s 5-year-old Empowerment Program as something of an insurgent effort, Jones says he “might want to see” all 352 schools work on some form of the empowerment model. “I think this model has tremendous potential in the district.” Jones recognizes that as society is plagued by increasingly intense challenges — hunger, illness, gang violence, bullying, teen sex — more pressure is placed upon our public schools.

“I’m not an excuse maker,” he says several times, noting that he willingly took the district’s top job, and he’s not shying away from what needs to be done. But education, Jones says, is about the basics. “I still say the main thing is the main thing. We have to educate the populace. Reading, writing and math matter a lot, and then the other piece is that folks have to have a sense of what our society is about — free enterprise, the political process. Schools have to maintain this American way of life, and you have to be able to read.”

During a recent conversation, Jones was told of the frustrations that many in this community have with the methodology used to determine high school graduation numbers. For years we’ve heard from high-level district officials that we live in a transient community, a place where families routinely move from neighborhood to neighborhood and often move out of state. We’re told that thousands of high school students are lost that way, many drop out, many more to attend school elsewhere. They return to California or Mexico or points beyond. When asked about those numbers Jones doesn’t shy away. He says he told district officials he wants data transparency, particularly for the graduation rate. He wants to know whether it’s 70 percent, 50 percent or something else.

“I’ve been on the job three months, and I still don’t know the numbers around the graduation rate,” Jones says. “I think the community understands we have some significant challenges. They’ll embrace and work with us, but not until we’re honest — right now we have a trust problem with our community. Until you tell the truth, you can’t get the community to embrace it and fix it.”

The full version of this story first appeared in the April 25 issue of VEGAS INC, a sister publication of the Sun.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy