Monday, Sept. 6, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Students back in class as district shows off newest school (8-30-2010)

- Ideas abound for curing what’s wrong with Nevada schools (8-30-2010)

- School District’s $54 million boost could mean 900 jobs (8-26-2010)

- New teachers talk about their careers, upcoming school year (8-22-2010)

- Sign of the times: Smaller class of new teachers (8-19-2010)

- Plummeting demand for teachers has silver lining (8-7-2010)

- Some teachers moving to Nevada struggle with licensing process (7-18-2010)

- Recruiting blitz on even as teachers await layoffs (4-27-2010)

- Teacher recruiting ‘not pretty,’ and it’s expected to get uglier (4-20-2010)

- After years of explosive growth, schools to feel economic pinch for years to come (3-25-2010)

- Teacher pay cut might not sting recruitment (1-12-2009)

Sun Coverage

Beyond the Sun

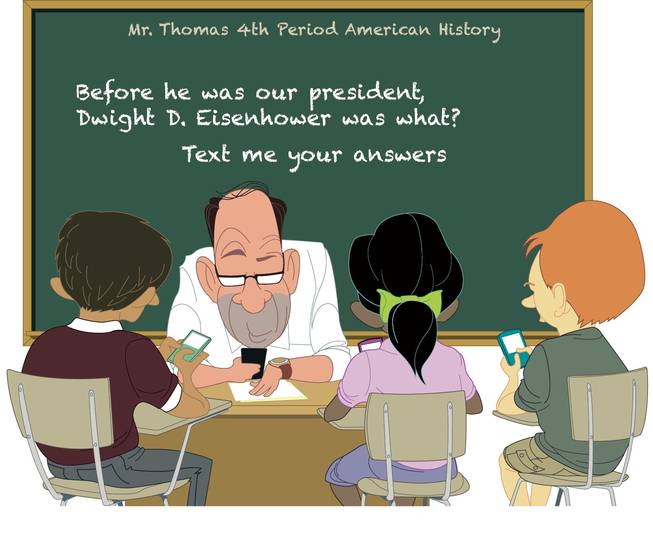

One day, not that far off, a teacher starting out on a genetics lesson may ask her middle school class, “How many of you can roll your tongue?” (It’s inherited.)

And instead of a wave of eager hands shooting up (or crossed arms and schoolchild indifference), 30 heads will hunch over cell phones, thumbs drumming, and text their answer to the teacher.

“Wow,” she will say, after looking at her cell phone, “40 percent of you can roll your tongue!”

Randy Thomas, the Clark County School District’s director of networking services and telecommunication services, said some children don’t want to be the only one to raise his or her hand, some children fear having the wrong answer.

The anonymity of texting gets more children to participate in class, if not actually learn something, teachers tell Thomas.

At any rate, the district is exploring what wireless can do.

For a cash-strapped school district, it means a new resource at little or no cost. Many students have cell phones and know how to use them. And under some service plans, the phones themselves are cheap or free.

Although the district is experimenting with pilot programs, a wireless classroom won’t happen overnight.

There are technical drawbacks (networks slow down with lots of users), security and distraction worries (how do you get children to pay attention in class while using a cell phone; how do you keep them from using it to cheat on tests?).

Of course, the superintendent must propose it, the School Board must approve it, and the public must be allowed to debate it.

Still, “we’re on the cusp of a paradigm shift,” Thomas said.

“The cell phone, the smart phone, is much more than a phone,” he said. “It’s a computer. Kids may not have what we used to think of as a computer at home. How can we leverage that in an educational environment?”

“Maybe in a class of 35 children, four children can’t afford a computer, four children have a really low-end computer that can’t run this application, another four children have computers that crash all the time, another four children have a computer that’s better than anyone else’s,” he said.

“So your district-provided computer is a minimum level of support.”

And outside computers complicate defending against computer viruses.

But even with unlimited tax revenue, there will never be enough computers for every child: There aren’t enough electrical outlets.

The district is experimenting gingerly with wireless. A pilot program allows students to use an iPod Touch.

One recently opened magnet school, West Career and Technical Academy, with 750 freshmen and sophomores, encourages students to bring their own laptops to use on the school’s wireless network.

But the wireless classroom is some time off.

On paper, current cell phone networks offer speedy access to the Internet. A typical wireless network might offer 50 megabits per second of bandwidth, 10 times what might be offered on a home network.

But as anyone who has ever used Wi-Fi at Starbucks or elsewhere knows, the more users there are, the slower the network becomes, whittling that 50 megabits into smaller and smaller slices.

The large computer behind the wireless network, like a waiter taking orders from a large party at a table, must pay attention.

“It has to talk with 30 people, but actually transition from person to person,” Thomas said. “It talks to you, transition, then it talks to you, transition.” The network slows down as a consequence.

“Everybody complains, and I get the service call,” he said.

Thomas’ network counterpart at UNLV had a crisis.

The system worked fine for casual use during the semester, but when an instructor decided to give the final exam online, assigning the computer to work beyond 100 percent, it crashed.

“You design for the worst case,” Thomas said. “But I’m sure it happens all the time — the people using the technology didn’t share their plans with the people designing the technology, and the people designing the technology didn’t bother to ask.”

And then there’s what Thomas calls the Burrito Problem. Wireless networks are open to small irritations, such as nearby microwave frequencies.

“Literally, if someone puts a burrito in a microwave oven in the next room, it could crash the wireless in this room,” he said.

Principals worry about other things. High school students being able to text means they could text anything, including answers to tests, said Ron Montoya, principal of Valley High School.

Discipline, always a problem, could go by the wayside. Cell phones would “make it impossible for a teacher to teach,” he said.

Clark High Principal Jill Pendleton worries about the fundamental fairness of requiring a potentially expensive piece of consumer electronics. “We have families who can’t even afford to buy shoes.”

And teachers worry about still other things. Ruben Murillo, president of the union representing the majority of the district’s 18,000 teachers, said he has no way of knowing what they think about cell phones.

“But I do know there are those who are really resistant to technology because they’re not tech-savvy,” he said.

On the other hand, some students think it would be terrific.

Mariah Eppes, 17, a senior and the Clark High student body president, realizes there are technical drawbacks. “But if there were airwaves just for schools, that would be cool!”

Zhan Okuda-Lim, 17, a senior at Valley High, said he was confident. “The friends that I have will use it for the right purpose.”

The change, if it comes, won’t be earthshaking.

“It’ll be like cell phones themselves,” Thomas said. “They were big, they were clunky, only a few people had them. They got smaller, they got cheaper, they got better and more people had them. The same thing is going to happen in the classroom.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy