Students walk outside for “morning muster” when they say the Pledge of Allegiance and listen to announcements at Fay Herron Elementary School in North Las Vegas Thursday, May 20, 2010.

Sunday, May 23, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sun archives

- Program for gifted students on hold amid budget crunch (5-18-2010)

- K-12 reform could leave Nevada behind (4-16-2010)

- Jump starting a proposed academy for the county’s top students (12-16-2009)

- School District falls short of ‘No Child’ goals (7-23-2009)

- GATE program opening doors for all students (4-22-2009)

Sun Coverage

Herron Elementary School

Good morning, my loves!

The principal can’t make it down the hall without stopping to hug someone. The little ones clasp her knees, the older ones reach for her waist. When she walks into a classroom to observe a teacher, the students sit up a little straighter. They offer shy smiles and enthusiastic waves.

This has been Kelly Sturdy’s home for seven years.

And the U.S. Education Department may force her out.

Under federal law, public schools that fail to improve test results over six consecutive years face sanctions, including possible takeover by the state. At the very least, districts are required to reorganize programs and replace key staff — typically starting with principals.

For six years running, Herron Elementary School has not improved enough its test results.

Federal law aside, there’s another reason for the Clark County School District to reassign her. Chronically underperforming schools can apply for extra federal money. To qualify, the district must replace principals and at least 50 percent of the staff.

For Herron to get the money, Sturdy has to go.

She doesn’t take it personally, of course. No more than she feels insulted that no less than five oversight committees are prowling around her campus, examining her administration and second-guessing her decisions. Or that she doesn’t know where she’ll be working in August. Or whether the innovative campus initiatives she fought for — some of which are finally bearing fruit — will be dismantled.

“If someone comes to me and tells me these kids would be better off if I move on, then that’s what has to happen,” Sturdy says. “It would break my heart to leave, but I really do want what’s best for them — not me.”

That’s been her mantra for 28 years.

•••

Sturdy grew up in Escanaba, Mich., a small city in the Upper Peninsula.

Her parents operated a mink ranch. All the children — nine girls and two boys — helped unload sacks of feed from delivery trucks and clean cages.

Her father didn’t finish high school. Her mother graduated, but there was no money for college. For Sturdy and her siblings, the question wasn’t whether they would go to college, but where.

Sturdy struggled in school in part because she was born with limited vision in her left eye. Things changed when she landed in Mr. Tippet’s sixth-grade class.

He sat her down, told her she was smart and that he believed in her.

“He told me, ‘You can do this, and you will do this,’ ” Sturdy says. “He stuck with me long enough that all my escape attempts didn’t work. From then on I was a straight-A student.”

It also planted the seed: Teachers help children.

After graduating high school, Sturdy enrolled at Michigan State University, intending to follow her mother’s wish that she become a chemical engineer. But two years into her studies, spending most of her time working alone in laboratories, Sturdy realized that wasn’t what she wanted.

Who am I helping?

Her academic counselor laid out the choices, and Sturdy picked: science teacher.

She told her parents. Her dad said he was OK with it — as long as she was working and productive, he was happy. Her mother balked.

Escanaba, Mich.

You know what they say, Kelly. Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach.

The words stung. But Sturdy completed her student teaching requirements, graduated and began looking for a job.

•••

It was 1982, and Michigan’s economy was plummeting in the midst of the nation’s oil crisis. Unemployment was creeping toward a record. There were no openings for teachers. People used to check the obituaries, and when a teacher died they would call the school and ask for an interview.

Sturdy found work wherever she could as a substitute teacher. It provided excellent training. Sturdy discovered, for instance, that if she didn’t win over the students at the outset, it would be chaos.

She learned to walk into a room and quickly figure out who the ringleader was, whom she needed to get on her side quickly to take control.

When no school needed her, she worked odd jobs. The most lucrative: at a meat packing company, assigned to the “kill floor.” Instead of wielding a piece of chalk at a blackboard, she wielded a high-pressure sprayer, washing beef carcasses after they had been skinned. The work wasn’t pleasant, but it was bearable, in part thanks to her years on the mink ranch.

After 18 months of patchwork employment, Sturdy started to question herself.

Is this going to be my life, waiting for somebody to die so I can get a teaching job?

“I honestly believe life happens while you’re making plans,” Sturdy says. “People end up in situations they never intended because time just passes. And that could have been me.”

•••

She was back at Michigan State working on her master’s degree — maybe it would help her get a job — when she wandered into a career fair.

Everyone else had appointments. Sturdy had none.

And neither did the recruiters from some school district out West. Having registered late for the job fair, they were still setting up their table when Sturdy walked by.

It was the Clark County School District.

Sturdy stopped to chat. And because there was no one scheduled after her, there was plenty of time to talk.

We like you, the recruiter told Sturdy after a bit. You’ll be hearing from us.

After almost three years of fruitless interviews in Michigan, Sturdy didn’t need a snow job.

“I told them, ‘You don’t have to be nice to me,’ ” Sturdy says. “And they said, ‘We’re serious. You’re going to hear from principals, and we’re going to offer you a job.’ ”

It wasn’t long after that the phone rang. It was the assistant principal of Moapa Valley High School, then set up for grades 6-12.

We think you’ll fit in well here. Want a job?

Sturdy wondered: Mo-whatValley?

She looked it up in an atlas and traced a trail along the Mojave Desert onto an Indian reservation.

Sturdy thought about the meat packing plant. And reading obituary pages. She was 24 years old.

I can do anything for a year.

•••

She loaded her belongings into a U-Haul trailer, hitched to her brown Oldsmobile Delta 88. Sturdy had a map to Moapa Valley, and her college roommate riding shotgun.

Nearly 2,000 miles later, they pulled up, as instructed, to the Rainbow Apartments, the only rental housing for miles.

Inside the apartment the lights were on. The fridge was stocked with juice and snacks. And there were six or seven notes waiting from the locals.

We’re glad you’re here! Come over for dinner!

The welcome was especially warm given that Sturdy had left home with hard feelings. Her mother still thought her daughter was making a mistake.

The Moapa Valley community became her new family. She adored the school — it was small enough that every face became familiar, but with plenty of challenges to fill the days. She taught physical education and science, coached cross-country and softball and even refereed the community soccer league.

Her mother flew out to check on Sturdy. She sat in the back of the class and watched her daughter teach.

“I could tell she was proud of me,” Sturdy says. “She liked seeing me up there.”

After that, there were annual visits. Sturdy’s mother and aunt would fly to Las Vegas, stay at Circus Circus and visit for a week or 10 days.

Her mother later apologized for suggesting that teachers are those “who can’t.”

You were right, her mother said. This is who you were meant to be.

Her mother died in 2002.

•••

In 1988, after three years in Moapa Valley, Sturdy was recruited to help open the new Martin Luther King Elementary School in Las Vegas.

She was going to the city.

At MLK, she taught fifth grade and marveled at a community growing so fast that a brand-new school would need portable classrooms. Within two years she moved to Fremont Middle School and taught science to sixth- and eighth-graders. When she decided to give her students the chance to see real dissections, Sturdy made a deal with a local pet store: She could collect snakes when they died, provided she turned over the skin. She buried the reptile’s remains in sandy desert soil in a wooden box, and put it on the school’s roof to dry out so that her students could have the fun of excavating it.

Her students sold doughnuts during recess to raise money for an overhead projector to view classroom demonstrations. When the time came to dig up the snake and do the dissection, hundreds of students gathered in the school’s courtyard to watch.

That wouldn’t happen today, Sturdy says — or at least, not without significant red tape.

“Now everything has to go through risk management, and the answer’s going to be ‘no,’ ” Sturdy says. “How do you create a sense of ownership in a school building, how do you get adults and children passionate about learning when there are so many rules? A lot of the fun has been taken out of it.”

•••

After five years in Clark County classrooms, Sturdy had started to imagine her future as principal. She got on the district’s administrative track, eventually earning a master’s and educational doctorate from UNLV.

In 1993, she moved back to Moapa Valley to Mack Lyon Middle School, serving as dean. She was assigned to Von Tobel Middle School in 1995, the first year the Las Vegas campus would be operating on a year-round schedule. Her boss, Ron Montoya, encouraged her to be creative and to put students first.

After being named Von Tobel’s assistant principal in 1996, Sturdy wanted to transform an unused wood shop into a computer lab, a relatively new concept. They had the computers but not the necessary utilities. When she crossed paths with a local electrician, Sturdy mentioned the computer lab and he offered his help. Within days a crew was climbing on the roof and detailing what was needed. His team brought in a crane to install the necessary transformers. When the school year started, Von Tobel’s students had their computer lab.

Sturdy was a key part of the team that transformed Von Tobel from a struggling campus to one that had few discipline issues, high test scores and strong parental involvement, Montoya says.

He remembers the day she even told him what to do: serve as an afternoon crossing guard.

“It was probably the best experience of my career,” Montoya says. “It taught me something about being accessible. Every parent and every kid knew where to find me after school.”

When you have good people working for you, Montoya says, “the best thing you can do is let them do their jobs.”

•••

There’s plenty to like about Fay Herron Elementary, a year-round campus that serves about 1,000 students drawn from hardscrabble North Las Vegas neighborhoods near Martin Luther King Boulevard. Built in the 1960s, the school was named for a longtime educator dedicated to working with underprivileged children. Over the past few years, the campus has gone through a phased renovation, with improvements such as classroom skylights and new landscaping. The walls were recently repainted a soft white, covering up the faded institutional gray. Students designed and painted the bright, ethnic murals on the exterior walls leading to the covered corridors. The classrooms are cheerfully decorated and carefully maintained.

When Sturdy arrived in January 2003 to take over as principal, she strengthened the prekindergarten program and then worked her way up through the grades. The school added intensive early literacy programs, tutoring and parent workshops so that families could be better prepared to help children with homework and enrichment activities. Extensive federal grants help to supplement the district’s basic support.

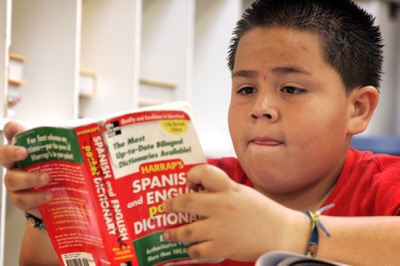

Almost 90 percent of the students are Hispanic and most have limited proficiency in English. As a result, most of the school’s classrooms follow a dual-language program where instructional time is divided between Spanish and English. Additionally, the entire school — including Sturdy — is expected to alternate speaking the two languages depending on the day of the week.

There’s little question that student achievement has improved during Sturdy’s tenure, although the gains haven’t been enough to meet all of the requirements of the federal No Child Left Behind Act. It’s a complicated matrix in which elementary schools must satisfy 135 categories, broken down by ethnicity, special education and socioeconomic status. A poor showing by just a handful of students can land an entire campus on the “needs improvement” list.

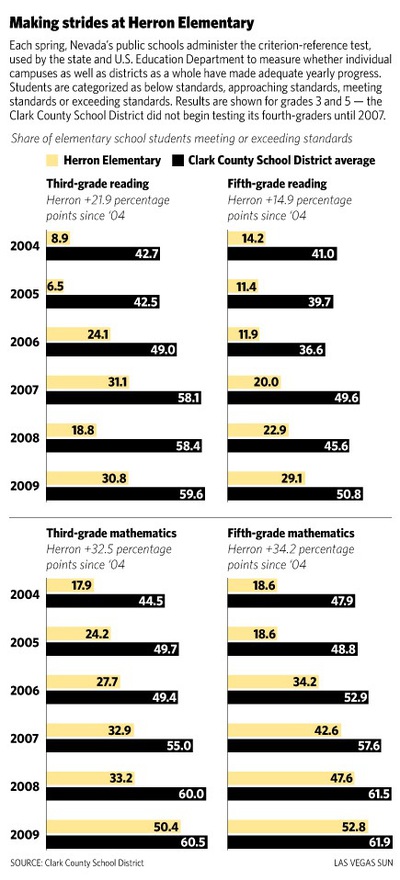

But Herron has made measurable strides. In 2004, just 18.6 percent of Herron’s fifth-graders met or exceeded the standard for proficiency in mathematics. By 2009, that figure had climbed to nearly 53 percent.

Most encouraging were the reading improvements among third-graders — a crucial age group because research suggests that children who aren’t reading at grade level by the time they enter fourth grade have only a 20 percent chance of catching up over the course of their academic careers.

By 2009, the percentage of Herron’s third-graders scoring in the lowest bracket had been cut in half to 15 percent.

Over the same five-year testing cycle, the percentage of third-graders meeting or exceeding standards soared to 31 percent from a dismal 9 percent in 2004.

On a recent morning, Sturdy waited in her office for teachers to collect plastic bins loaded with testing materials for the criterion-reference test, used by Nevada to measure whether a school has made enough progress to satisfy state and federal requirements.

One by one, four teachers stopped by to claim a bucket, count the test booklets and answer sheets, and sign the checkout sheet.

They then headed to the same classroom to collect their students.

All four teachers were needed to help administer tests to just 24 students, who will be separated depending on their needs. Some need the math questions read to them in Spanish. Others need the entire test read aloud. A small number will take the English-only version of the test, but still need a teacher to serve as proctor. It’s a complicated process that takes time — and teachers — away from regular instruction.

This spring, Herron was required to test about 450 students in grades 3-5. More than 350 of them get special handling at test time.

This is not the only challenge facing Sturdy and her staff. The school has one of the highest transiency rates in the district. Since September, she’s lost dozens of students who were on track to make the grade. Those seats have been filled by newcomers, most of whom arrived testing below their grade levels. Those new students’ scores won’t count against Herron when the end-of-the-year report cards are handed out.

But they will be used to measure Sturdy’s performance.

•••

Sturdy has dedicated her career to at-risk students. She understands the challenges faced by parents who often work two jobs and rely on extended family to help raise their children. Her husband is in construction, and the recession has meant having to take jobs farther from home.

Their son attended Herron from kindergarten through fifth grade, making it easier for her to start early in the morning and leave late — sometimes very late — in the day. He’s now in middle school, and Sturdy empathizes with parents who complain that schools are slow in returning phone calls — and relates as well with school staff who bemoan a lack of parental patience.

She can remember the days when she kept a loaf of bread and a jar of peanut butter in her desk to make quick snacks for hungry students who found their way into her office. Today, with the help of community volunteer groups, Herron hands out nutritious snacks every Friday to help students get through the long weekend. The school serves breakfast to nearly every student every weekday morning because children can’t learn when they are hungry.

For many Herron students, after-hours events at school are their only opportunities to further improve their academic skills.

At a family math night, teachers — staying late — lead teams of parents and students through a series of hands-on learning activities scattered across the campus. In a small annex off the lunchroom, several mothers supervise preparations for a spaghetti dinner that will follow.

Sturdy had been observing a toddler for some time, sensing something’s not quite right. He’s not walking as well as he should, and doesn’t make eye contact. She plucks him up and dances a little jig with him, hoping to coax a smile.

The 2-year-old’s mother is one of the school’s more active parent volunteers, with several children enrolled at Herron.

Sturdy says she will tell his mother of a state-funded early intervention program to evaluate preschool age children and identify potential problems.

As she carries him around the room, pointing to the students racing by with measuring tape and assignment sheets, he seems to perk up and take in more of what’s going on.

“He needs to realize there is more to life than sitting in the stroller,” Sturdy says. “There’s probably absolutely nothing wrong with him, other than he needs more one-on-one.”

And we can do that!

Delmy Hernandez, one of the spaghetti dinner volunteers, has heard the rumor that Sturdy might not be back in August. That worries her and many other parents, says Hernandez, whose five children have attended Herron or are enrolled.

Hernandez recalls last year when the fifth-graders spent the night at Mount Charleston on a field trip. One of the students felt ill, and it was Sturdy who stayed up with her until dawn.

“Dr. Sturdy was just being her mom because the girl’s real mother couldn’t be there,” says Hernandez, tears coming to her eyes at the memory. “I’ve never seen that between a teacher figure and a child before. She calls everyone ‘My love,’ and she means it.”

The school environment is welcoming, Hernandez says. There’s constant communication from teachers and opportunities for parents to get involved.

“Some of us can’t contribute moneywise, but any little bit can help,” Hernandez says. “Dr. Sturdy wants us here. It gives you that feeling that we’re really all a family.”

•••

Still, there’s no shortage of people telling Sturdy what she’s doing wrong.

This year, five groups of experts are visiting the campus. There’s the “improvement team” sent by the Nevada Education Department, as required by No Child Left Behind’s list of fixes for chronically struggling campuses. And there’s an improvement team from the School District’s region office. Two federal reviews are under way, one focusing on programs funded under Title I and another looking at services for English-language learners. And there’s a district team focused on the campus reorganization plan — the one that might evict Sturdy.

One day in October, Sturdy walked down the hall from her office to the conference room to meet with the state support team. She was politely asked to step out.

She shrugged and left.

When the team made its next visit, Sturdy wasn’t shooed away.

“So many times the rules change in the middle of the game,” Sturdy says. “You get used to it.”

She worries more about what the sudden shifts in direction are doing to her teachers.

Like the time when the entire staff met over three days to write the school’s improvement plan, only to have it discarded in favor of the restructuring blueprint that will come from the central office.

And the time one of the improvement teams told the teachers to write year-end goals on a blackboard so they would be on constant display, only for another improvement team to countermand the instructions: Just write down current goals.

So much of this isn’t about the students, Sturdy says, but about jumping through hoops to satisfy federal regulations. With No Child Left Behind up for reauthorization, there’s a chance that schools such as Herron might finally get credit for steady progress, even if the specific goals aren’t met.

“It would be great just to hear someone tell us, ‘Good job,’ ” Sturdy says.

•••

With just a few months left in the academic year, Sturdy doesn’t know where she’ll be in the fall.

“I know absolutely nothing,” Sturdy says. “I don’t think it’s because the central office is deliberately shutting me out. People just don’t know.”

If she’s told that someone else can do a better at Herron, Sturdy says she won’t fight being reassigned. Maybe a change really would be the best thing.

Life happens while you’re busy making plans.

Andre Denson, the district associate superintendent who oversees Herron, says he understands Sturdy’s frustrations — and agrees that having five “improvement” teams giving often-contradictory orders “is not only excessive, it’s absurd.”

While the district has to follow federal and state mandates, it’s expected that individual principals will still be accountable for a school’s success, Denson says.

“The bottom line is everything (from the outside teams) is taken as a recommendation,” Denson says. “The principal still has the final say.”

Whether Sturdy will have the final say at Herron for the 2010-11 academic year will be decided this summer, Denson says.

If Sturdy is reassigned, it shouldn’t be construed as “punishment,” Denson says. He noted plenty of schools in the district have managed to meet the demands of No Child Left Behind and “stay off everybody’s lists” but can’t boast the kind of growth that has taken place across grade levels at Herron.

“I’m a fan of Dr. Sturdy — she’s a strong principal and an advocate for children,” says Denson, who worked with her at Von Tobel. “My son attended Herron, so I’m speaking as a parent as well. I’ve seen firsthand the strength of her programs.”

•••

There’s no question that No Child Left Behind needs a serious overhaul, and many of the Obama administration’s proposals are sound, says Gail Connelly, executive director of the National Association of Elementary School Principals.

But the inflexible insistence that principals be replaced at low-performing campuses — a requirement of one of the grant programs — is shortsighted, Connelly says.

“You run the risk of chasing away a principal who makes a difference in favor of a quick fix that we know will not help sustain the kind of change that needs to take place over time if children are to show measurable growth,” Connelly says. “Really great leaders are going to be forced to leave, and we wonder who will replace them.”

And that’s a real concern: Who’s waiting in the wings?

The Clark County School District’s budget crisis has stifled efforts to groom the next generation of campus leaders. Nearly 100 assistant principals and deans were sent back to classroom positions as a cost-saving measure. Among them was Anthony Nunez, who had been assigned as Sturdy’s assistant principal at Herron last fall. Nunez, who joined the district in 2004 as part of the first Teach for America corps, was also the first alumnus of that program to be promoted to an administrative post.

Nunez says he was disappointed not to be able to return to Herron in the fall, particularly given the amount of time he had spent working with improvement teams. But he understands the budget crisis made the reassignment necessary.

“I’m just grateful to have had this year’s experience at Herron,” Nunez says. “It’s an amazing school. I’ve learned a lot from Dr. Sturdy, and I’ll take that with me.”

•••

Sturdy wonders sometimes what she could do — how much she could accomplish as a school leader — if she were working on a more level playing field, if her students didn’t show up to school with a crushing load of challenges. What if she were dealt better cards?

It’s something Sturdy thinks about now that her own future is uncertain.

Life’s what happens when you’re busy making plans.

Maybe she would put in for an assignment at an “average” district school, one where she wouldn’t have to pull all-nighters to finish a grant application, or worry about students coming to school hungry.

But then she thinks about how much she cares about the students at Herron, how the campus feels like a home. She thinks about the dual-language program, which is just hitting its stride, and the parent academies and her wonderful staff.

During a meeting with Denson, he asked her where she wanted to be in the fall.

“I told him I’ll go where the community needs me,” Sturdy says. “I’ve loved every school I worked at, whether it was as a teacher or an administrator. I love what I do. I’ll do it anywhere.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy