Friday, July 23, 2010 | 2:01 a.m.

Sun coverage

Voting expenses

Here’s a breakdown of School Board campaign spending so far,* as well as the per-vote cost for each candidate in the June primary:

District D

Lorraine Alderman

Contributions: $1,250

Expenditures: 0

Votes: 3,764

Cost per vote: $0

•••

Javier Trujillo

Contributions: $18,934

Expenditures: $12,392

Votes: 2,530

Cost per vote: $4.90

District F

Carolyn Edwards

Contributions: $21,982

Expenditures: $15,313

Votes: 8,738

Cost per vote: $1.75

•••

Ken Small

Contributions: $2,151

Expenditures: $8,427**

Votes: 7,730

Cost per vote: $1.09

District G

Erin Cranor

Contributions: $20,767

Expenditures: $19,026

Votes: 5,796

Cost per vote: $3.28

•••

James Brooks

Contributions: $0

Expenditures: $0

Votes: 4,327

Cost per vote: $0

*First deadline for candidates to report contributions and expenses was June 1. Additional reports due Oct. 26 and Jan. 15, 2011.

**Expenditures include $6,276 of own money.

The Clark County School District receives more tax dollars than any other entity in the state. It’s also the state’s largest public employer, with more than 38,000 employees. The School Board — seven members elected from geographic regions — controls an operating budget of $2.1 billion, sets policy for the nation’s fifth-largest district and hires the superintendent.

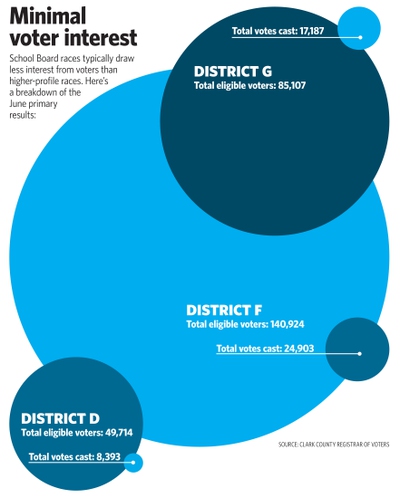

But the races to fill three seats on the board — only one of which is defended by an incumbent — have so far drawn only minimal interest from voters.

In the June primary, hundreds of thousands of voters opted not to cast a vote for School Board, with the overall turnout ranging from 17 to 20 percent (overall turnout countywide was 26 percent).

The vote total for Districts D, F and G was 50,478 — less than the number of votes garnered by third-place finishers in other races.

School Board races are typically “minimally funded, and for better or for worse interest groups such as gaming, unions and construction don’t get involved,” said Eric Herzik, a political-science professor at UNR. “In theory, this is grass-roots politics at its best. Citizen candidates are stepping up to take on a very important, and generally thankless, job.”

In theory, the races would generate a broad pool of candidates and significant financial support from interested backers. But the opposite is more typical.

And it doesn’t take much in the way of financial contributions to mount a winning campaign. In the June primary, retired district Administrator Lorraine Alderman finished first in the District D race without spending a dime. And James Brooks, a 2008 graduate of Valley High School who is attending College of Southern Nevada, came in second in the District G race without a single campaign expenditure. Erin Cranor, a longtime district volunteer, finished first in the District G race, spending $19,026 — or $3.28 for each of the 5,796 votes she received.

Architect Ken Small, who came in second in the District F race, spent $8,427 as of June 1, including $6,276 of his own money. His opponent, Carolyn Edwards, the current School Board vice president seeking her second term, spent $15,313 of the nearly $22,000 she has raised.

Only about 1,000 votes separated the two candidates in the primary, and Small said a big part of his strategy is to get people who skipped the June election to support him, rather than simply focusing on trying to win over voters who have already decided to support Edwards.

Small, who has been a vocal critic of the district’s decision to build more schools even after enrollment began to decline, said he doesn’t intend to do much fundraising and will not solicit money from anyone who might have business before the School Board. He criticized Edwards for taking contributions from architecture firms and builders who have been involved in school construction.

But Edwards said that those few individual contributions are relatively small — topping out at $1,500 — and in no way influence her decisions.

In the District D race, Alderman, who spent 25 years with the district after five years at UNLV, attributed her primary victory to her name recognition and “the sling vote.” She broke her shoulder in the spring, and walked the district with her arm immobilized.

Rather than spend money on professional fliers, Alderman used her home printer and an existing stock of blank business cards, which she handed out as she made her rounds. She intends to fundraise for the general election, and capitalize on her name recognition.

“People know me, and they know I put students first,” said Alderman, who coordinated the district’s charter schools program.

Her opponent and the second-place finisher in the primary is Javier Trujillo, a former School District arts administrator who now works for Henderson’s intergovernmental relations division. Trujillo, who was responsible for the district’s popular mariachi music program, called the overall voter turnout in District D “dismal,” and said he’s working hard to rally support for November.

“It’s important that people be engaged and involved in the School Board’s work,” Trujillo said. “When we talk about the future of the state’s economy, we’re talking about education.”

In other states, a seat on the school board is typically considered a starting point for individuals with aspirations for a career in public service. But the Clark County School Board hasn’t typically served a similar purpose (recent exceptions include County Commissioner Susan Brager and Las Vegas Councilwoman Lois Tarkanian).

That’s in part because of Nevada’s reliance on “citizen legislators.” Most of the state’s lawmakers have full-time jobs in a variety of fields, and having experience at the local level is considered less essential for those running for state Assembly or Senate.

And for Brooks, who will face front-runner Cranor in the District G race, the entire concept of “experience” is highly overrated.

“Look at the current School Board — experience got us where we are today,” Brooks, 20, said.

Brooks, who has volunteered to help speech and debate teams at several high schools, said his focus is on giving students better teachers. The district was so busy over the past decade building schools and hiring staff to fill vacancies that quantity took precedent over quality, he said.

“Now that the growth has slowed down, it’s time to weed out the teachers who shouldn’t be there,” he said.

As for his plans for the general election, Brooks said he’s getting ready to launch a campaign website and will be walking the district.

But Cranor, who has served seven years on the district’s school attendance zone advisory commission and has four children in public schools, said there’s no substitute for experience. She’s become a familiar face at School Board meetings in recent years, calling for greater transparency on how the district spends its proceeds from bond campaigns and questioning policies related to year-round schools.

Cranor spent many past campaign seasons walking precincts on behalf of other candidates and education-related causes. Now that her name is on the ballot, she’s noticed a shift in the public’s response when she rings the doorbell.

“I’m getting the feeling that more people are paying attention to education. Maybe in the past we were complacent because the economy was good. Now more people realize education is the key to Nevada building a future for itself.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy