Monday, Jan. 25, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Carl Icahn group gets licensing to run 3 Nevada casinos (1-21-2010)

- Regulators recommend Carl Icahn’s plans for Nevada properties (1-6-2010)

- Tropicana Las Vegas emerges from bankruptcy (7-2-2009)

- Equity firm plans to take over Tropicana (5-15-2009)

- Tropicana reorganization plan gets court’s OK (5-5-2009)

- Tropicana creditors want Vegas property split from company (3-24-2009)

- Tropicana could emerge from Chapter 11 in May (3-6-2009)

- Plan would give Tropicana creditors ownership stake (1-13-2009)

- New blood helped Tropicana, union heal old wounds (8-27-2008)

- Tropicana Entertainment makes money but still files for bankruptcy (5-5-2008)

As the first major casino company set to emerge from bankruptcy in the recession, Tropicana Entertainment offers a beacon of hope for cash-strapped companies in the throes of the worst downturn this industry has ever seen.

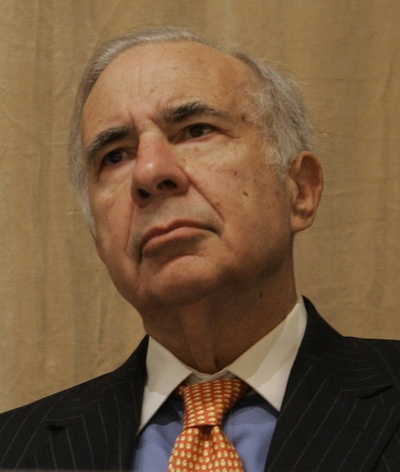

Less than two years after its bankruptcy filing, Tropicana Entertainment’s debt has been wiped clean, and the company’s new owner, billionaire Carl Icahn, is injecting $150 million to pay creditors and upgrade properties.

The company is expected to come out of bankruptcy this month. Employees, including those at the MontBleu in Lake Tahoe and the Tropicana and River Palms in Laughlin, can expect to hold onto jobs that were uncertain before and during bankruptcy. (The Tropicana in Las Vegas is not owned by Tropicana Entertainment.)

“This word, bankruptcy, frightens people. But it’s been incredibly beneficial for us,” Tropicana Entertainment CEO Scott Butera says.

The corporation’s drop into bankruptcy traces back to former owner Bill Yung’s pricey, boom-era gamble in 2007 — the purchase of Aztar casino chain, which saddled it with $2.7 billion in debt the same year the economy started its downturn.

Yung had made a fortune operating run-of-the-mill Marriotts and other midmarket hotels. He hoped to increase profits at his newly acquired casinos by reducing overhead, which included layoffs.

That turned out to be a bad idea made worse by the recession, as employees and customers complained about dirty rooms, poor service and short-staffed areas. (New ownership has corrected these problems.)

The company suffered a major blow in December 2007 when New Jersey regulators revoked its license to operate the Tropicana in Atlantic City, forcing the sale of one of its largest and most profitable assets.

Before bankruptcy, increased competition in Laughlin and a poor ski season and summer wildfires near Lake Tahoe didn’t help.

In the end, it was the recession — which has humbled even industry giants — that pushed Tropicana Entertainment to the brink.

In May 2008, months before financial problems at other casino companies would make headlines, Tropicana Entertainment sought bankruptcy protection.

Rather than attempt to negotiate deals with lenders outside of bankruptcy as some companies have done, Butera didn’t hesitate to enter Bankruptcy Court even though his casinos were still making money.

Net operating revenue grew 77 percent in 2007 after the Aztar acquisition. But expenses rose 210 percent, resulting in a net loss of $1 billion. A big chunk of that went to interest payments on the company’s mammoth debt. Tropicana Entertainment entered bankruptcy with debts about equal to its $2.8 billion in assets.

Now, including Tropicana Atlantic City, which Icahn purchased separately out of bankruptcy, the company’s nine casinos are on track to generate about $700 million in cash per year.

That might not sound like much for a company that once generated more than $1 billion a year, but such comparisons aren’t what matter nowadays, Butera says. What matters is having low debt, or, better yet, none.

“Clearly revenue is down, but the idea is to make money,” he says.

Many casino companies — including several that are close to bankruptcy or may avoid bankruptcy altogether — are hamstrung by lenders who are owed billions of dollars and, in some cases, have mortgage rights on casinos.

Many companies try to avoid filing for bankruptcy at all costs because it can spook business partners, vendors and employees. Better capitalized companies often poach customers and employees from competitors during bankruptcy reorganization, when a company’s costs are tightly controlled and monitored by Bankruptcy Court, says Matt Sodl, president of Innovation Capital Investment Bankers, a company that assists casinos in the purchase, sale and reorganization process.

“The well-heeled companies will typically outspend and outpromote” those in bankruptcy, he says.

Negotiating such minefields properly can result in long-term rewards, especially as casinos, without the burden of debt, are good cash generators.

“Companies that operate under tight budget constraints because their debt is too high are not going to be able to compete,” Sodl says.

Bankruptcy still has negative connotations in the casino industry, thanks in part to Donald Trump, whose Atlantic City casinos have entered bankruptcy for a third time.

Not surprisingly, The Donald — whose casino company sought bankruptcy protection last February — has a breezy attitude toward the process.

“It doesn’t matter — it’s a modern-day thing, a legal mechanism,” he told the New York Daily News during his last round in Bankruptcy Court in 2004, as if referring to a new way of sending text messages.

Butera, the former investment banker who engineered Trump’s second exit from bankruptcy in 2005, is careful to distinguish Tropicana Entertainment’s reorganization from Trump’s troubled history with restructurings that didn’t stick.

Tropicana Entertainment is debt-free and better positioned for growth than Trump, Butera says, because its nine properties are scattered across seven markets in five states.

“Being diversified is a good thing because different markets perform differently at different times,” he says.

It’s a business cliché that has proved true in the recession’s hammering of Las Vegas and Atlantic City more than smaller casino markets.

In other respects, the Tropicana bankruptcy, while perhaps cleaner on paper, has been more difficult to execute, he says.

Butera took the reins after lenders booted Yung from the company, a process more complete than Trump’s loss of control over his company in bankruptcy.

Yet Tropicana Entertainment, unlike Trump, was a fundamentally mismanaged company attempting to repair its image with state regulators, Butera says.

In New Jersey, regulators called out Yung for various violations, including his failure to adequately staff the Tropicana Atlantic City. Regulators revoked his casino license in New Jersey, setting in motion the fire sale of the property to Icahn, his company’s Chapter 11 filing and his own exit.

Tropicana Entertainment moved to the nation’s gambling capital in 2008 and, with new general managers running its casinos, is operating under different guidelines.

“We literally had to deconstruct this company and rebuild it from scratch,” Butera says. “It was very, very challenging.”

Company financial records reveal ample opportunity to capitalize on this fresh start. Excluding the Tropicana Atlantic City, the company is generating just under $400 million in revenue compared with $450 million a year ago — a small drop relative to peers. Profits, Butera says, are down less than that under new management, which is spending less on giveaways that inflated revenue without boosting profit.

And the restructuring will continue even after the company comes out of bankruptcy, he says. Newly appointed managers with decades of casino experience will be tasked with making the company more efficient — without resorting to layoffs, Butera says.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy