Clark County School District Superintendent Walt Rulffes is a finalist for the national “Superintendent of the Year” award.

Tuesday, Jan. 12, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- How Gibbon’s proposed cutbacks might be felt in classrooms (1-7-2010)

- Superintendent Walt Rulffes: Schools need plan of action for success (12-27-2009)

- Rulffes has rough draft of fix for Prime Six (9-10-2009)

- What fine print of federal plan means for our local schools (9-2-2009)

- U.S. schools chief seeks big changes, has money to spend (8-30-2009)

- Sought: More schools like West Prep (8-27-2009)

- School District again taking heat for unequal achievement (8-16-2009)

Sun Coverage

Beyond the Sun

Four years ago, the decision on who should lead the beleaguered Clark County School District came down to two men who offered distinctly different styles: Walt Rulffes, who had run the district’s finances and was holding the top job on a temporary basis; and Eric Nadelstern, a veteran educator lauded for his innovative approach to accountability in New York City Public Schools.

Nadelstern was recruited by a group of Nevada business and civic leaders who praised him as an agent of change. The group, calling itself the Council for a Better Nevada, said the School District under Rulffes would just be more of the same — which at the time was no compliment.

When Nadelstern withdrew from consideration, the Clark County School Board gave the job to Rulffes.

And he’s shown to be not more of the same.

Rulffes is one of four finalists for the honor of “Superintendent of the Year,” awarded by the American Association of School Administrators. He will appear today at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., with the other finalists — the superintendents in Tuscaloosa, Ala.; Jefferson County, Colo.; and Washington County, Md. The winner will be announced next month.

“I hope I’ve proven I’m not the ‘status quo guy,’ ” Rulffes said. “But then, I never believed that to begin with.”

Indeed, Rulffes has won over many of his past critics. And although the district continues to have its struggles and challenges — a soaring population of at-risk students, increased demands for academic progress by the federal government and an economy that has forced more than $250 million in budget cuts — his leadership is cited as a district bright spot.

“He’s shown a tremendous ability to look at existing challenges that have never been addressed and find new ways to answer them,” said Maureen Peckman, executive director of the Council for a Better Nevada.

In selecting Rulffes as a finalist, the association cited student achievement, staff development and parental involvement, as well as the district’s school empowerment program and his fiscal management of the nation’s fifth-largest district. Judges are evaluating leadership, communication, professionalism and community involvement.

To be sure, when compared with other states, Nevada has languished near or at the bottom of too many lists, including student achievement and education spending. Locally, Clark County hasn’t fared much better. Consider:

• The graduation rate has improved to 65 percent from 60 percent four years ago, but the dropout rate continues to hover under 6 percent, down only slightly from high of 7.1 percent in 2005.

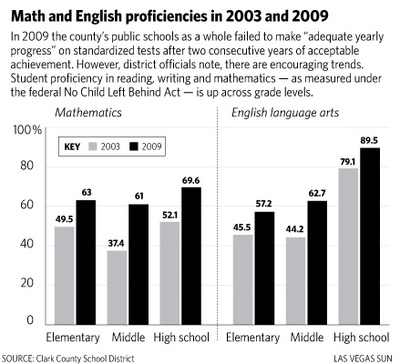

• In 2009 the county’s public schools as a whole failed to make “adequate yearly progress” on standardized tests after two consecutive years of acceptable achievement.

However, district officials note, there are encouraging trends:

• While the dropout rate hasn’t improved much, neither has it worsened in the worst economy since the Great Depression.

• The percentage of students who require remediation when they get to a state university or college has declined to 24 percent from 40 percent, thanks to intensive interventions and new partnerships that Rulffes helped establish.

• The district is also doing a better job helping recent dropouts — young adults ages 18 to 21 — come back to school and try again. The Adult Education program overall has seen its numbers soar.

• Student proficiency in reading, writing and mathematics — as measured under the federal No Child Left Behind Act — is up across grade levels.

• The district’s investment in career and technical academies, which prepare students for college-level academics and jobs in high-need areas such as health care, is showing early promise.

• And the empowerment schools pilot program, which gives principals additional funding and greater control over operations in exchange for stricter accountability, is poised to expand.

• Rulffes is raising the bar in other ways, as well. The graduation requirement has been increased to include a fourth year of mathematics.

Outsiders have taken note. Districts from across the country send representatives for a closer look at Clark County’s prototype designs for energy-efficient schools, its career and technical academies and the district’s music program, widely considered one of the best in the nation.

Rulffes has also developed a reputation for taking swift action after missteps.

When West Las Vegas community leaders complained that a preliminary blueprint to fix inequities in six elementary schools had been assembled without their input, Rulffes withdrew his proposal and vowed that the public would have its say.

After concerns were raised last year about the district’s overtime costs, Rulffes implemented new policies that cut those costs by over 55 percent.

And then, there were the math tests.

Until two years ago, teachers used their own exams to determine a student’s grade in algebra and geometry. But the district wanted a uniform measure of how well students were learning and whether they would be ready for a tougher statewide proficiency exam in 2010.

The dismal results on the new uniform test last school year took everyone by surprise. Ninety-one percent of Algebra 1 students and 86 percent of Algebra 2 students failed. Eighty-eight percent of geometry students failed.

“One of my darkest professional days is when I saw those first results,” Rulffes said. “But I’m glad we faced up to the issue, and didn’t push it aside as many districts have done.”

He has since formed an expert committee to find the root of the problem and help the district address it.

“If I felt like nothing was being done and we were sliding backward, then I would have a problem with our superintendent,” School Board President Terri Janison said. “Do I wish the progress was faster? Of course I do. But we’re talking about education, and you can’t expect people to embrace change overnight.”

Rulffes handled the district’s math crisis head-on, which wasn’t an easy approach, UNLV President Neal Smatresk said. There’s no shortage of people telling Rulffes where the district has gone wrong and how to fix it, which can be tough to navigate, he said.

“You can get so caught up in the public element of an office that it becomes nearly impossible to deliver any kind of change,” Smatresk said. “I don’t think Walt’s fallen into that trap. You have to court the outside community, but you also have to know what works inside. It would be easy to be sidetracked by the many conflicting views ... and find yourself nearly paralyzed.”

Budget cuts have made the job more difficult, eliminating popular campus programs and reducing support staff. Rulffes’ background in finance has helped, said John Jasonek, executive director of the Clark County Education Association, which represents the majority of the district’s 18,000 teachers.

“Just keeping the schools running right now is a victory,” Jasonek said. “You’re fooling yourself if you think in this budget climate, in a state ranked last in the nation for education spending, that schools can do much more than that. But the truth of the matter is that no teacher lost a job last year, and education can’t happen without teachers teaching kids.”

One of Rulffes’ greatest strengths might be his ability to turn critics into allies.

When the Council for a Better Nevada lost its horse in the superintendent race, Rulffes courted its members to support his empowerment schools program. It’s similar to the “autonomy zone” Nadelstern created in New York City.

In 2008, with Peckman acting as intermediary, the Lincy Foundation announced a $13.5 million donation. (The timing of the gift was critical — the state had recently announced it was rescinding its empowerment funding because of the budget crisis.)

“We found a really good way to work with him,” Peckman said. “There are many stakeholders in this community who believe in what he’s doing.”

Peckman praised Rulffes’ implementation of a districtwide report card that sets three-year goals and measures progress in dozens of categories, such as closing the achievement gap between minority students and their white peers. The report card is more comprehensive than what’s required by the federal No Child Left Behind Act, which measures student achievement on standardized tests.

Creating the report card “took guts and showed a lot of accountability,” Peckman said. “Unless you’re honest about where you are, you can’t be honest about where you’re going to be.”

Rulffes’ contract runs through the end of the summer, but it automatically renews unless he decides he doesn’t want an extension or the School Board takes action.

It appears based on his job evaluations that when Rulffes leaves, it will be on his terms.

For now, rather than talk about his own future, Rulffes prefers to focus on more immediate challenges facing the district — building stronger ties with businesses to support campus reform, preparing for an influx of millions of dollars in federal grants to overhaul low-performing campuses, expanding gifted and talented education and developing a system for teacher merit pay.

“I really enjoy my work,” Rulffes said. “I think I have the best job of any superintendent in the country.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy